Dorothy L. Sayers at Oxford

'Scholar; Master of Arts; Domina Magistra'

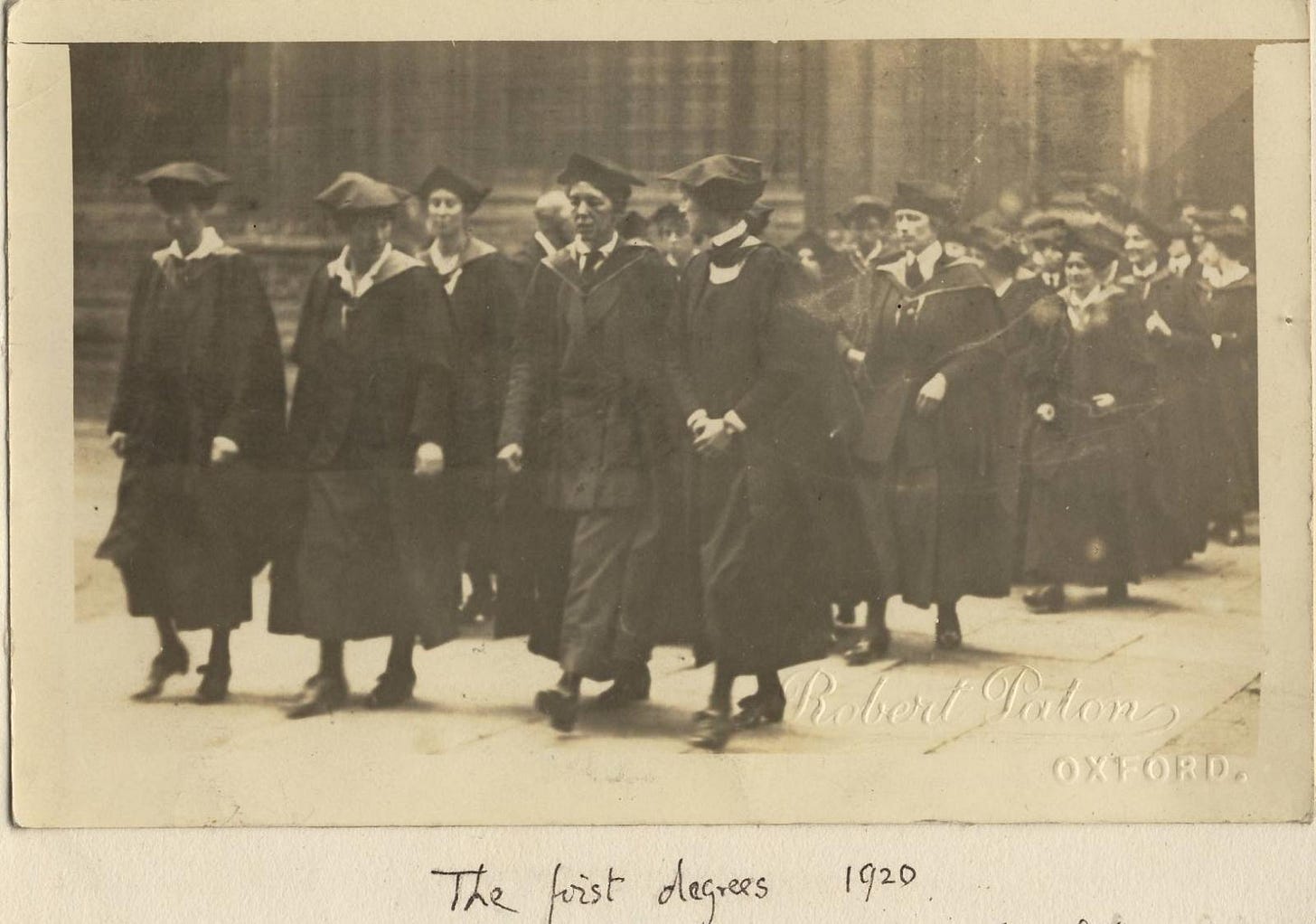

The first Oxford University graduation ceremony to award degrees to women took place on 14 October 1920. 27-year-old Dorothy L. Sayers was among the fifty celebrants that day, and she never forgot it. This short piece about the lasting effect of that day was inspired by a lovely post by

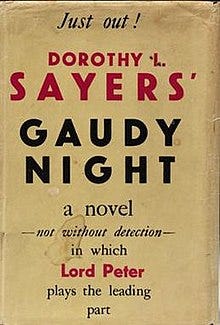

called ‘Harriet and Lord Peter’ about Sayers’s 1935 novel, Gaudy Night.We’ll be discussing this novel in July as part of our 20th-Century Book Club for paid subscribers (see schedule at the bottom of this post). I very much hope you’ll join us.

Oxford University’s first graduation day for women was a degree ceremony like no other. Never before had a Vice-Chancellor uttered the ceremonial Latin words ‘Domina, Magistra’ in the feminine gender, and the vast, high-ceilinged auditorium of the beautiful Sheldonian Theatre rang with the cheers of family and friends as twenty-seven-year old Dorothy L. Sayers walked up to the stage to be awarded her first-class Master’s degree. She had actually completed her studies in modern languages at Somerville College five years before, and was working in a school in France, but she was determined not to miss out on this historic occasion. She had requested her place at the ceremony, as she explained to her mother, ‘because I want so much to be in the first batch. It will be so much more amusing.’

The women’s long-awaited recognition at Oxford was celebrated at Somerville that evening with a special dinner presided over by the College Principal, Emily Penrose, who since 1907 had made sure that all her students fulfilled the requirements for an Oxford degree. It was attended by former Somerville students Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby, among others, and the guest of honour was Professor Gilbert Murray, a classical scholar and long-time supporter of women’s right to study at Oxford. His friend, Jane Ellen Harrison, a lecturer in classical archaeology at Newnham College in Cambridge, was jealous. ‘I gnash my teeth when I think of all your Somerville young women preening in cap and gown,’ she told Murray. ‘So like Oxford and so low to start after us and get in first!’

The two Cambridge women’s colleges, Girton and Newnham, had become established almost ten years before Oxford’s Somerville and Lady Margaret Hall. But the 1920 Oxford ceremony gave hope to Harrison and others that soon Cambridge women too would be permitted the degrees they had earned. But the following year, a move to award the title of degrees to women was defeated, and the University of Cambridge did not confer degrees on women until 1948, 28 years after Oxford (see my post about the 1897 protests here).

When Dorothy L. Sayers began studying modern languages at Somerville in 1912 it was still, technically, not a college but an ‘affiliated women’s society’ within Oxford University. Somerville women were called ‘freaks’ by male students because of what was seen as their ‘unnatural’ devotion to learning. In her first term, Sayers started up a literary society with a handful of other women students, which they named the Mutual Admiration Society. Despite the jokey name, it was ‘a subversive community within an institution where women were constantly reminded that their talents were not wholly welcome’, as Francesca Wade puts it (p.100).

Dorothy Sayers knew she had a passion for writing but typically she played down her talents (‘I write prose uncommonly badly, and can’t get ideas’). Only her close friends in the Mutual Admiration Society knew how much she adored what she called ‘lowbrow’ crime fiction. While at Oxford she began to publish more highbrow poetry and essays, but the possibility of actually making a living as a writer seemed as far-fetched as the plots in the novels she devoured. She was aware that the great majority of women students, no matter their subject of study, took up teaching after university: ‘all that she sees before her, unless she has exceptional talent, is teaching’ observed the economist Clara Collet in 1902 (Sutherland, p.26)

After she completed her studies in 1915 Sayers wanted to do something different, but was not yet sure what that would be. So in 1916 she accepted a job in teaching (modern languages at a girls’ school in Hull), before returning to Oxford the following year to work for publisher and bookseller Basil Blackwell. But she soon found that, as Mo Moulton writes in The Mutual Admiration Society, ‘a single woman who was neither a student nor an academic had no obvious place in Oxford society’. (p.79) Her landladies were deeply suspicious of Sayers’s wish to hold literary salons for Somerville students and, on one occasion, a respectable tea party for wounded soldiers. One landlady told her that she would rather have a badly behaved male undergraduate as a lodger than ‘a permanent woman’.

Cursed with hearts and brains

‘London itself’, wrote Virginia Woolf in 1928, ‘perpetually attracts, stimulates, gives me a play and a story and a poem, without any trouble save that of moving my legs through the streets.’ Francesca Wade’s Square Haunting: Five women, freedom and London between the wars

After her graduation day, Sayers decided that her life had to change. She moved to London, took on translating work and did some part-time teaching to make ends meet, then in December 1920 found an unfurnished room to rent on the eastern, unfashionable fringe of Bloomsbury. Francesca Wade’s Square Haunting is an engaging evocation of Sayers’s years in in Mecklenburgh Square, where her lodgings had the advantage of being cheap and close to the British Library. On her application form to use the library’s reading room, Sayers proudly wrote down her academic status: ‘a Master of Arts at Oxford’. She informed the authorities that she was planning a D.Phil. thesis called ‘the Permanent Elements in Popular Heroic Fiction, with a Special Study of Modern Criminological Romance.’

This may have been partly true. After her undergraduate studies Sayers did consider staying on as a don at Somerville, but decided that she was ‘too sociable’ to spend her life in a women’s college. There was no doubt that she had the intellectual ability to become a scholar – her later translation of Dante’s The Divine Comedy is acclaimed [see comment by Frances below] – but at heart, she wanted to earn her living as a crime writer. She had always loved detective novels, and devoured the popular Sexton Blake thrillers as a student, but knew that her secret wish to write such stories herself would not be seen as worthy of an Oxford graduate.

But now in London, as she mixed with bohemian writers and artists in the evenings and went to see Grand Guignol plays near the Strand, she began to view crime fiction in a different, more professional light. In an unpublished essay, probably written in the British Library in 1921, she addresses the fictional Miss Dryasdust, M.A., who ‘disapproves of my fondness for detective stories of the more popular kind.’

Sayers argues with Miss Dryasdust, telling her that she is wrong, and that crime fiction holds the same place in the contemporary imagination as Beowulf and the heroic epics of ancient Greece once did. Miss Dryasdust, with her prized Master of Arts Oxford degree, might be the alter ego of Dorothy L. Sayers herself, who could have pursued her research interests at Somerville College instead of living precariously in cheap lodgings in London.

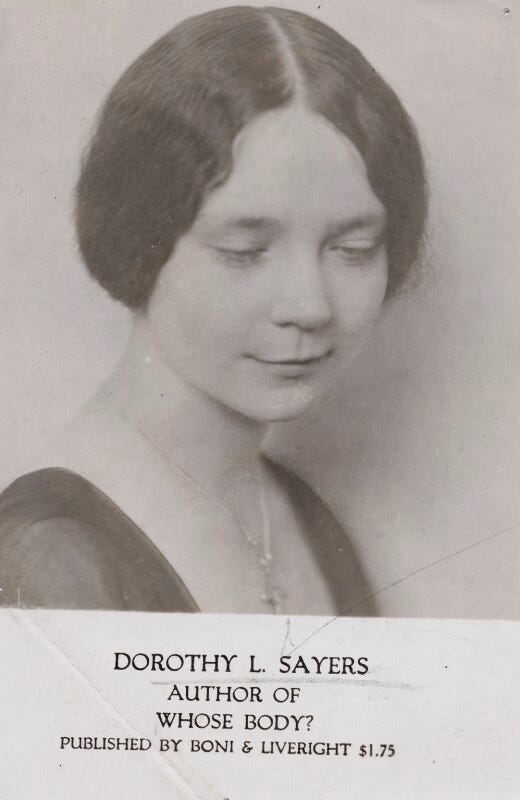

But London, with all its creative stimulus, was where Sayers needed to be to write. In January 1921, she began sketching out an idea for her first book, which was published in the U.S.A. in 1922 by Boni & Liveright as Whose Body? By April 1923 Whose Body? had been acquired by Fisher Unwin in the UK, and introduced Lord Peter Wimsey to the world.

Wimsey would be the aristocratic, athletic and intelligent protagonist of several of Sayers’s most successful novels and stories. He delights in solving mysteries, apparently for his own amusement, and embodies the opposite of everything in her own life in Mecklenburgh Square, as she later recalled:

‘After all it cost me nothing and at the time I was particularly hard up and it gave me pleasure to spend his fortune for him. When I was dissatisfied with my single unfurnished room I took a luxurious flat for him in Piccadilly. When my cheap rug got a hole in it, I ordered him an Aubusson carpet.’

Wimsey is presented in a light-hearted way, with his monocle, rare-book collection and love of dashing sports cars, but Sayers also gives him a backstory that informs his moral judgment. When he discovers the identity of the murderer in Whose Body? he finds himself shaking, and his teeth chatter, as if back under attack in the trenches of the First World War. This was at a time when the British medical establishment decided that ‘shell shock’ was no longer worth taking seriously.

It was not until Strong Poison (1930) that Sayers introduced the character who was much closer to herself: the beautiful, intelligent Harriet Vane, who is accused of poisoning her former lover Philip Boyes. Wimsey helps to save her from the gallows, but when he proposes marriage to her, she turn him down flat. In Have His Carcase (1932) the couple work together to solve a murder, and Wimsey proposes again. But Harriet is determined to retain her independence and unwilling to acknowledge the ‘detestable burden of gratitude’ she owes him.

In Gaudy Night (1935) Lord Wimsey has a lesser role (despite the claim on the original cover, see below), though ultimately a very romantic one. But it is really Harriet Vane’s novel. At the start of the book she has spent three years travelling (partly to avoid Wimsey) and has become a successful crime writer. She now lives in a comfortable flat in Mecklenburgh Square and is invited to return to her former college (here named Shrewsbury) to help the academic women there solve a series of hate crimes. As she hesitates, wondering how her old college will welcome her, she realizes that these were the women who taught her to value her own intellectual ability and independence. The three years she spent among them as a student at Oxford University enabled her to achieve the successful creative life that she had always wanted.

‘Whatever I may have done since, this remains’, Harriet Vane reminds herself sternly. ‘Scholar; Master of Arts; Domina; Senior Member of this University’. Her voice could be that of Dorothy L. Sayers herself, whose time at Oxford helped to give her the confidence to become the writer that she had always dreamed of being.

Thank you for reading this, and I’d love to hear what Dorothy L. Sayers means to you. If you’d like to join our paid-subscriber reading and discussion of her outstanding 1935 novel, GAUDY NIGHT, coming up in July 2025, here’s the schedule:

28/29 June More about the stories of the women who belonged to the ‘Mutual Admiration Society’ along with Dorothy L. Sayers at Oxford.

5/6 July Introduction to some of the background of this novel, and Gaudy Night discussion part 1 (chapters 1-11)

19/20 July Gaudy Night discussion part 2 (chapters 12 – 23)

Further reading

Vera Brittain, The Women At Oxford: a Fragment of History (Harrap, 1960); Ellen Brundrige, 'Translations of Latin in Dorothy Sayers' Gaudy Night'; Janet Howarth,'"In Oxford... but not of Oxford": the women's colleges', History of the University of Oxford, ed. Brock and Curthoys, vol VII (OUP, 2000) pp 237-307; Mo Moulton, The Mutual Admiration Society: How Dorothy L. Sayers and her Oxford Circle Remade the World for Women (Basic Books, New York, 2019); Dorothy L. Sayers, Gaudy Night (Gollancz, 1935); ‘How I Came to Invent the Character of Lord Peter Wimsey’ quoted in Barbara Reynolds, Dorothy L. Sayers: Her Life and Soul (1997); Gillian Sutherland, In Search of the New Woman: Middle-Class Women and Work in Britain 1870-1914 (CUP, 2015); Francesca Wade, Square Haunting: Five Women, Freedom and London Between the Wars (Faber & Faber, 2020).

My TLS review from 2020 is here. See also ‘Celebrating 100 years of degrees for women’ Somerville College website, October 7, 2020. ‘Women making history: 100 years of Oxford degrees for women’, University of Oxford website, 2020.

Connecting threads (1)

In May 1927, Virginia Woolf gave a lecture at Oxford called ‘Poetry, Fiction and the Future’ and among the audience was a young undergraduate called Gertrude Trevelyan who listened to Woolf’s words about a new type of fiction carefully. A month later Trevelyan became the first woman student to win Oxford University’s most prestigious poetry prize, a huge achievement at a time when the rights of women at Oxford were being contested yet again. The story begins with Virginia Woolf recording her sense of awe after seeing the total eclipse over Yorkshire in 1927.

Many thanks for this most welcome essay on Dorothy Sayers. I studied Italian literature under her friend and colleague Barbara Reynolds. She told us that after translating the Inferno and Purgatorio, Sayers turned away from the Divine Comedy, for a little light relief, to the translation of some of Petrarch’s sonnets, and died before completing the greater task. BR then banged the table and said: ‘And there’s a lesson to us all!’ There was only a handful of sleepy students round the table and none of us looked capable of much. But of course it was Reynolds who finished off the translation of Paradiso.

Thanks for this, Ann. Academia is such a double-edged sword. The education is liberating, but, oh, the politics, not to mention the increasingly brutal standards for intellectual activity, particularly in the humanities. How interesting to think of DLS running into all of this so long ago . The misogyny is underground now, but still there. And her struggle with her inner academic over writing genre fiction is also fascinating. I understand!