Leaving Ireland

Brian Moore's The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne (1955)

Hello, and welcome/fáilte! This week’s post is about an Irish-Canadian writer whose books I have loved for many years. Back in the late 1970s, in the war-torn north of Ireland, a young English Literature teacher told her class of recalcitrant teenagers (including me) that if they wanted to read good writing, they should get hold of a copy of The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne by a writer from Belfast called Brian Moore. Reading it completely changed my view of what a novel could do. Here’s my St Patrick’s Day celebration of this extraordinary novel, and a special teacher.

Introduction

In his last essay, ‘Going Home’, published posthumously in 1999, the Irish-Canadian author Brian Moore wrote about a recent visit he’d made to Connemara in the west of Ireland. In a small field he came across the gravestone of a very old family friend, Bulmer Hobson, and seeing this name unexpectedly brought ‘vivid and importunate’ memories of his childhood and adolescence growing up in a doctor’s family in Belfast, and the reasons why he left.

‘There are those who choose to leave home vowing never to return and those who, forced to leave for economic reasons, remain in thrall to a dream of the land they left behind. And then there are those stateless wanderers who, finding the larger world into which they have stumbled vast, varied and exciting, become confused in their loyalties and lose their sense of home. I am one of those wanderers.’ (Brian Moore, ‘Going Home’)

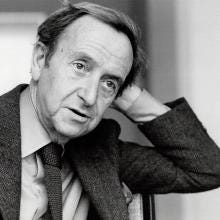

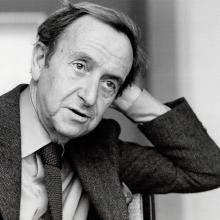

In 1943, when he was 22, Brian Moore left the bombed-out city, having joined the British Army in a noncombatant role. After the war he lived and worked in Eastern Europe, then moved to Canada in 1947 and became a Canadian citizen shortly afterwards. He began his writing career by publishing thrillers under a pseudonym, but it was not until 1955, when The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne was published in the UK under his own name, that he considered himself to be a writer. It’s a novel that explains, in some ways, the reasons why he left Ireland (‘vowing never to return’, it seems). But in his later life he started to feel differently about his home.

The essay below was first published by Slightly Foxed magazine and is republished here with their kind permission.

Coming Home

Ann Kennedy Smith

We first meet the eponymous heroine of Brian Moore’s novel The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne (1955) shortly after she has moved into her new lodgings. As she carefully unpacks a silver-framed photograph of her Aunt D’Arcy and a religious image of the Sacred Heart, we sense her misgivings about ‘the condition of the bed-springs, the shabbiness of the furniture and the run-down part of Belfast in which the room was situated’.

Judith Hearne is an unmarried, middle-aged woman living on precarious means in the 1950s. Both Miss Hearne (as she is always known) and the boarding-house have seen better days, but she does not dwell on her reduced circumstances for long. She takes pride in her neat appearance, devout Roman Catholicism and grammar-school education. The sparse furniture in her rented room can be moved to hide the stains, and her two pictures are comforting talismans: ‘When they’re with me, watching over me, a new place becomes home.’

Belfast is the setting for this modern classic about self-delusion, spiritual crisis and an awakening to a new truth. The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne made its author famous and put the city on the world literary map. For the latter part of the twentieth century, however, Northern Ireland was a place associated with bitter conflict, not bleak social comedy. I was fortunate enough to grow up in a peaceful seaside town there, but when I first read Moore’s novel in the 1980s, Belfast had long been ravaged by the Troubles. Perhaps it was because of this that Bruce Beresford’s 1987 film of the book relocated the story to Dublin. Maggie Smith and Bob Hoskins are excellent actors, but the book’s essential Northern Irish geography is missing.

Brian Moore was born in 1921 and grew up in Clifton Street, then an affluent part of Belfast close to busy Royal Avenue. His father was a prominent surgeon and the first Catholic to be appointed to the Senate of Queen’s University; his mother Eileen was a nurse from Donegal, twenty years younger than her husband. Dr James Moore’s surgery was on the ground floor of their tall Victorian house, while Brian (always pronounced ‘Bree-an’ in the Gaelic way by his family) and his eight siblings spent their days in the spacious rooms above with their mother, nursemaid Nellie and two maiden aunts. Moore later described it as a ‘house of women’. Just opposite was the Central Orange Hall with a statue of a conquering King William III on horseback on the roof, a constant reminder of the social and religious divisions of the city.

‘Belfast and my childhood have made me suspicious of faiths, allegiances, certainties,’ Moore wrote. ‘It is time to leave home.’ Aged 22, having failed at university and abandoned his Catholicism, he knew that to become a writer he would have to leave Ireland, just as his literary hero James Joyce had done before him. The Second World War gave him the opportunity. In 1943, as German bombs rained down on Belfast, he joined the British Army and served as an administrator on the edge of war zones in North Africa, Italy and France.

After the war, he worked for the United Nations in Warsaw. This international experience introduced him, as his biographer Denis Sampson observes, ‘to a world without national or ethnic borders’ and made a lasting impact on his imagination. In his later novels he often returned to those places that he called his ‘emotional territories’, and explored his fictional characters’ inner conflicts in times and places as far apart as seventeenth-century Canada in Black Robe (1985), 1940s eastern Europe in The Colour of Blood (1987) and modern-day Haiti in No Other Life (1993).

In 1947 Moore settled in Montreal, where he found a job as a journalist and wrote a series of bestselling thrillers under pseudonyms. He married Jackie, a French-Canadian fellow journalist, and just before their son Michael was born in 1953, he became a Canadian citizen. By then, he was already at work on his first serious novel, one in which he would return to Belfast to ‘write it out of my system’, he thought. Only later did he realize that as well as setting out the bitter reasons why he had left Ireland, his novel touched on his own loneliness as an exile.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cambridge Ladies' Dining Society to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.