Light and shade

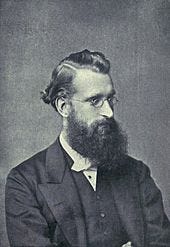

‘Nobody,’ said Ruskin, ‘will believe that the main virtue of Turner is in his drawing.’ The Oxford professor and author of Modern Painters, published in five volumes from 1843-60, was giving a public lecture called ‘Light and Shade’ on a Thursday afternoon in Oxford, 9 February 1871. Ruskin told his audience, packed into the Sheldonian theatre, that he was convinced that J.M.W. Turner’s genius as an artist lay in his skills as a draughtsman rather than as a colourist.

One young woman in the audience who was hanging on Ruskin's every word was twenty-year-old Louise von Glehn from London. She was visiting Oxford for the first time, and she adored Ruskin’s writings on art. He was, she told her friends, her prophet.

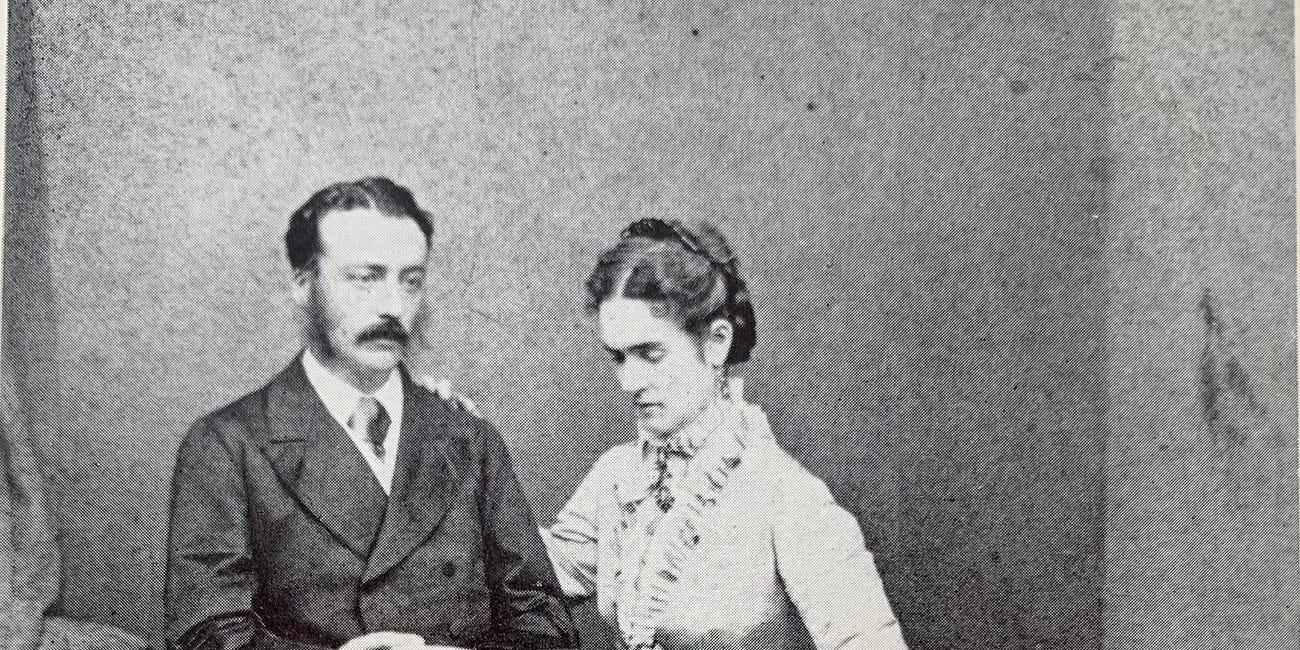

It was ironic that at this lecture on the virtues of monochrome, Louise should have chosen to wear a striking yellow scarf. It caught the eye of Mandell Creighton, a tall, art-loving 27-year-old fellow of Merton College, Oxford. He asked to be introduced to ‘the girl who has the courage to wear yellow’, and she was instantly struck by Mandell’s self-confidence. ‘How dull everyone else has seemed to me in comparison,’ she later wrote.

Marriage to Mandell

According to Oxford and Cambridge’s constitutional statutes, university lecturers were not permitted to marry. But some colleges were beginning to relax their requirements for promising fellows, and Merton did not want to lose Mandell Creighton, a gifted teacher and scholar who, unusually for an intellectual of that time, had taken religious orders.

Louise and Mandell (or ‘Max’ as she always called him) married in January 1872 and settled in the St Giles area of Oxford, in a modern villa which they named ‘Middlemarch’ after George Eliot's novel. Both Louise and Mandell gave their artistic tastes free rein in their new home, decorating the drawing-room with Burne-Jones prints, old oak furniture, a blue carpet and the yellow wallpaper they both loved.

The Creightons adored each other, but from the beginning it was a stormy relationship. Urbane and witty in public, Mandell was frequently critical and demanding at home, and ‘not the sort of husband who overlooks one’s faults’, Louise told her sister three months after her wedding, adding stoically that ‘nothing could be better for me.’ She was never afraid to take issue with him, although she always preferred it when they came to an agreement. Her friend Bertha Johnson painted her portrait at this time, looking soulful against a Morris-like trellis of roses, but Louise was no wistful pre-Raphaelite heroine. In contrast to Mandell, she had a direct manner in public which some people found rather unexpected in a Victorian woman.

Education for women

Louise Creighton would have loved the chance to study at university herself. Before moving to Oxford she had taken London University's first higher examination for women, and passed with honours: 'had circumstances permitted it,' she wrote wistfully later, 'I might have become a real grubbing student'. Instead, she found another way to be involved.

The first ‘Lectures for Ladies’ had begun in Cambridge in 1871, and Louise and her friends Mary Augusta Ward and Clara Pater decided that Oxford needed to catch up. In 1873 they helped to set up a committee to organize the first women's lectures and classes at Oxford University. In 1877 this became the Association for the Higher Education of Women, and within two years Oxford's first colleges for women, Lady Margaret Hall (1878) and Somerville (1879) were established.

From Oxford to Cambridge

From 1875 until 1884 the Creightons lived in Embleton, Northumberland where Mandell Creighton took up the post of country vicar and worked on the first volumes of his extensive papal history. Louise combined home-educating their six children with writing and publishing a popular series of history books. In 1884 Mandell accepted the offer of the professorship of ecclesiastical history at Cambridge University, and the family and their servants decamped to a rented house on the edge of the town, where their seventh child was born.

Louise Creighton was happy to be among Cambridge’s first generation of academic wives, and in her characteristically efficient way she decided that she would make particular friends with Ida Darwin, Fanny Prothero and Kathleen Lyttelton. Kathleen and Louise had much in common: they were both published writers married to ambitious academic clergymen, and they shared a strong interest in education and professional opportunities for women. But soon one issue would threaten to divide them.

Louise had stayed in touch with her Oxford friends Clara Pater, by now a classics lecturer at Somerville College (later she would become the young Virginia Woolf’s tutor) and Mary Ward, who as 'Mrs Humphry Ward' was achieving modest success as a writer. Her novel about a doubting cleric, Robert Elsmere, published in 1888, would propel her into the literary spotlight; it was an immediate bestseller and Gladstone wrote a long review praising it in the prestigious literary journal The Nineteenth Century. The journal's editor J.T. Knowles, keen to boost circulation figures, suggested that Mrs Humphry Ward should use her newfound celebrity status to organize a manifesto against the growing support for women's suffrage in the UK.

Ward asked her old friend Louise Creighton for help, and together they gathered the signatures of 104 well-known women for a public letter. It was published in the June 1889 issue of The Nineteenth Century and widely reported in the press, as the canny Knowles knew it would be. He saw to it that their letter would be argued against eloquently in the following issue in a lengthy riposte by the influential suffragists Millicent Garrett Fawcett and Emilia Dilke.

But in Cambridge there were personal friendships at stake. Kathleen Lyttelton was distressed by her friend's anti-suffrage stance, and asked her to reconsider. Instead, Louise chose to double down, and in August 1889 The Nineteenth Century published her six-page 'Rejoinder' to Millicent Fawcett, stating her own belief that a wife was by her nature 'purer, nobler, more unselfish' than her husband and that giving the vote to women would 'lower the ideal of womanhood among men'. It was Louise Creighton’s first step onto the national stage, and made her famous. But later she would regret her involvement in the controversial manifesto, saying simply 'I think this was a mistake on my part.'

Forming the Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society

The following year, 1890, Louise Creighton and Kathleen Lyttelton put their differences aside and asked a small group of their Cambridge friends to form a women’s dining and discussion club, which they called the Ladies' Dining Society. It was successful despite – or perhaps because of – the different opinions held by the twelve women, and the group continued to meet until the First World War.

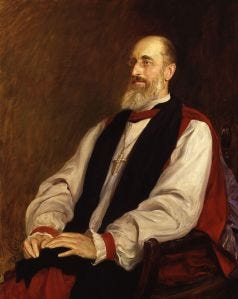

The Creightons moved away from Cambridge in 1891 when Mandell accepted a bishopric at Peterborough, and later London, but Louise remained a key figure in the dining club; she regularly travelled back to Cambridge for their meetings, or invited the group to the bishop's palace at Peterborough, and later Lambeth Palace in London.

Louise and Kathleen’s friendship became close again when both women became key figures in the National Union of Women Workers (now known as the NCW), a non-political organization founded in response to the unsatisfactory working conditions faced by many women at the time. Louise Creighton became its first president in 1895.

A change of heart?

In January 1901 Mandell Creighton, by now Bishop of London, died aged 57, just days before the death of Queen Victoria. Louise was overcome with grief at the loss of her husband, but threw herself into her work. She moved to a grace-and-favour apartment at Hampton Court (perhaps

is familiar with it?) and set about writing her Life and Letters of Mandell Creighton, which was published in two volumes in 1904 and acclaimed by Lytton Strachey as one of the great biographies. Then there were also several volumes of Mandell's speeches and writings to edit and publish. Louise Creighton wanted to ensure that her clever, complex husband was understood by future generations, and she used her considerable skills as a writer and historian to do so.At the 1906 conference of the National Union of Women Workers held at Tunbridge Wells, Louise stood on the platform and made a bombshell announcement. She told her audience that she had changed her mind about women's suffrage, and from now on she would give her full support to the parliamentary campaign for women to have the vote. Mrs Humphry Ward was furious, and tried to talk her friend out of it, but Louise was once again resolute. Ward’s subsequent involvement in the ‘Women's National Anti-Suffrage League' helped to delay the vote for women for many more years. Today Mary Ward is justly remembered for her significant contribution to women's education and her work to establish childcare provision. But she is also notorious for standing in the way of equal rights, as John Sutherland writes.

Privately, Louise Creighton worried that people would think it was Mandell's death that had allowed her to express her pro-suffrage opinions freely for the first time. Was there not some truth in this? In her unpublished memoir she considers the question carefully, and tries to be as truthful as if Max himself had turned his penetrating eyes on her.

‘I certainly should not after he was a bishop or indeed at any time' she writes, 'have taken up a line opposed to him in any public opinion’.

But I think Louise sounds uncharacteristically hesitant on this issue. ‘I do not think he was at all strongly opposed to female suffrage at any time,’ is how she tactfully puts it. Did her loyalty to Mandell Creighton, and willingness to preserve his posthumous reputation, get in the way of her own clear thinking as a historian?

As Ruskin said in 1871, when Louise's yellow scarf attracted Mandell’s eye, there is light and shade in everything.

Louise Creighton continued to publish history books, biographies and, perhaps most surprisingly, a treatise on venereal disease. She served on two Royal Commissions, gave lectures at the London School of Economics and in the 1920s was elected to the governing body of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. As a moderate Christian feminist she worked hard to reconcile liberal and conservative factions in the Anglican Church. As her biographer James Thayne Covert noted: 'In her later life she pondered the question of the priesthood of women. She recognized that her opposition to it was rooted in instinct and prejudice, and she could find no logical reason against it.'

Sources: James Thayne Covert, ‘Creighton, Louise Hume (1850–1936)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 and A Victorian marriage: Mandell and Louise Creighton (2000) Louise Creighton, Life and letters of Mandell Creighton, 2 vols. (1904); Memoir of a Victorian woman: reflections of Louise Creighton, 1850–1936, edited by J. T. Covert (1994).

Thank you for reading, and if you’ve been enjoying my writing, please consider a paid subscription. It really does help me to keep doing this work, and gives you access to the 20th-century Book Club and all other Cambridge Ladies Dining Society posts.

The Cambridge bride

On the way to a lovely summer wedding held in an English country garden last weekend, I spotted a bride and groom sitting on a bench at the Baker Street stop on the London Underground. As I took a snap of the happy couple, seemingly bathed in celestial light from the window above, there was an audible ‘Aaaah!’ from other passengers who were happy to wit…

Fascinating story (her work, her friends, her decisions, her marriage…) And beautifully told, as always.

Ann, this is fascinating for quite a few reasons, starting with Turner as a draughtsman. What a surprise, but who am I to argue with Ruskin? Eminent women campaigning against suffrage: another surprise. Finally and fundamentally, Louise’s brave admission to her change of heart and the possible influence of her late husband on her previous position. What she feared he believed, or might believe, could be more powerful here than his actual beliefs.