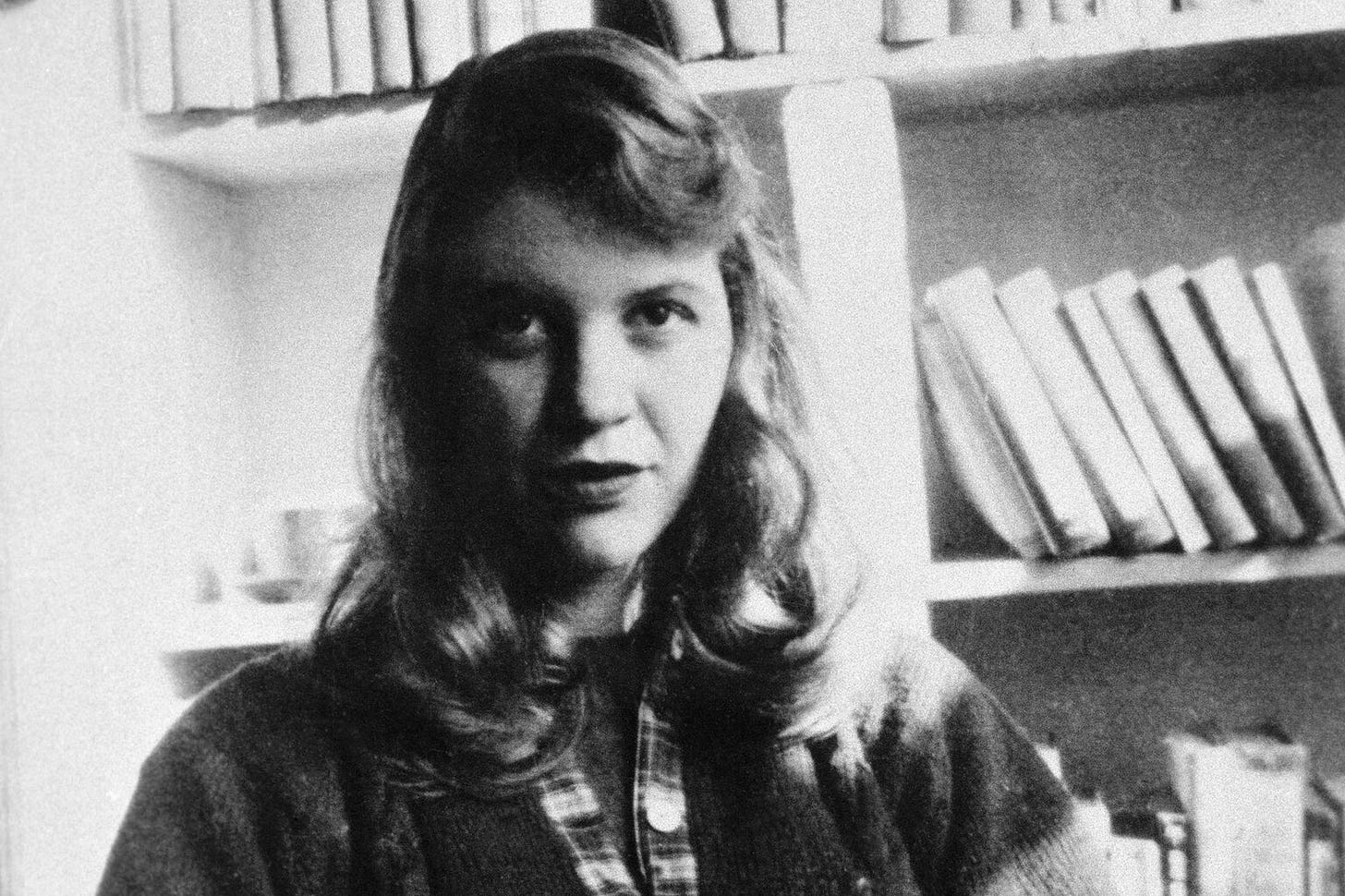

‘On Dec. 7th a new life will begin,’ Sylvia Plath confidently wrote in a letter home to her mother in Massachusetts. December 7th 1956 was when Cambridge University’s Michaelmas term ended, and the date that Plath, who until then had been in student halls, officially moved into her first married accommodation. ‘Home’ for the next six months would be a rented flat at 55 Eltisley Avenue, a Victorian terrace near Newnham College where she was in her final year of an English Literature degree.

They had married in London six months previously, but had kept their marriage a secret from everyone but their immediate families and a few trusted friends. Following advice from Sylvia’s mother Aurelia, they had both agreed to tell no one about their marriage until Plath had taken her final Tripos exams in May 1957.