Becoming Sylvia (1 of 2)

'Long live the hedgerows!' Introducing Sylvia Townsend Warner (1893-1978)

Hello, and a very warm welcome to Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society. Today’s post for paid subscribers features a short introduction to the life of Sylvia Townsend Warner (1893-1978), as a prelude to discussing her novel Lolly Willowes (1926). If you’d like to know more, do have a look at my free post on 20th-century books here. Read on for a quick round-up of this week’s book news and literary links.

Book news

There’s no paywall this weekend on all Times and Sunday Times articles. You can read about the best-selling books that defined each decade, short articles about lesser-known novels in the excellent ‘Re-Reading’ series, and

’s take on Sally Rooney’s latest.‘What I’d like to read — what I’d like to write — is a book about women who became writers despite their mothers,’ writes

in Works in Progress, ‘a sort of mash-up of Phyllis Rose’s Parallel Lives and Colm Tóibín’s two books on men who write and their parents.’What makes a good book review? I recently wrote about the gentle art of book reviewing for the ‘bona-fide literary salon’ that is Inner Life. And I was very chuffed to get a mention on the cover of the TLS last week, see below.

If you’re keen on foraged fare and discovering inventive ways of cooking scavenged fruits and vegetables, sign up for the wonderfully named ‘Fruits of the Forage’ by

(Laura Willowes would approve). I also enjoyed this interview on ’s ‘Beyond the Bookshelf’ with Eleanor Anstruther, who says: ‘I read every day for about an hour. It’s the same practice as writing. Little and often, a sustained, repetitive schedule that moves mountains.’‘Long live the hedgerows!’ is the rather excellent slogan of the charming Sherlock & Pages bookshop in Frome, Somerset. Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes was, apparently, one of the best-selling books last year.

A kind reader has alerted me to this recent YouTube episode featuring Sylvia Townsend Warner’s writing locations in Dorset (it’s well worth watching). Visible Women UK are currently fundraising for a statue of STW in Dorchester, and say that any leftover funds will be used to conserve her archive.

There are still a few tickets left for this live Substack event in London I’m taking part in on 27 March. Hope you can come along. But now, back to Sylvia Townsend Warner’s early life, with thanks to

for sharing this marvellous book cover based on a London Transport poster.

Becoming Sylvia

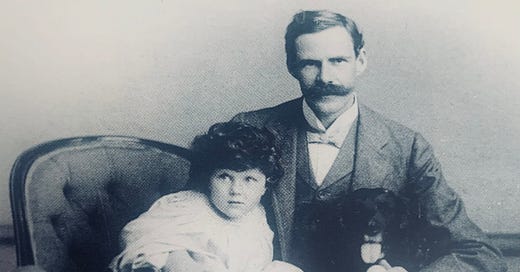

Sylvia Townsend Warner was born on 6 December 1893, at Harrow-on-the-Hill in Middlesex. She was the first and, as it turned out, the only child of George Townsend Warner and his wife Nora, née Huddleston. Nora had been brought up in colonial extravagance in Madras, India, where her father was a colonel in the Indian Army; the family’s fortune was lost when a bank collapsed, and they had to move back to England. Nora’s passion for fashionable dress-making, playing the piano, and recalling her colourful past, never left her. ‘My mother’s recollections of her childhood in India were so vivid to her that they became inseparably part of my own childhood,’ her daughter Sylvia later wrote.1

Sylvia grew up in the environs of the prestigious Harrow School for boys, where her father George taught history. Before becoming a schoolmaster, he had been an outstanding student at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he was taught by the eminent historian Mandell Creighton. Improving the teaching of history at Harrow became George’s lifelong mission, and he challenged his pupils to think and respond for themselves. He was also a stickler for a good essay-writing style. The novelist L.P. Hartley recalled George telling him, of a schoolboy blunder he made, ‘If you ever say that again I shall fall on you with my teeth and my umbrella.’

From the moment she was born, George adored his little daughter. Her first lessons were when her father recited the poetry of Keats and Elizabeth Barrett Browning while riding a rocking-horse with her. Sylvia’s ability to learn was prodigious, and she became his star student: as a teenager she was referred to as ‘the best boy at Harrow’ and her father included an early of essay of hers in his textbook, On the Writing of English. Nora taught her to read and ignited her imagination as a young child with stories, but lost interest as her daughter grew older and less appealing. ‘For the first seven years of my life I interested her heart,’ Sylvia wrote, ‘I was an amusing engaging child, and she enjoyed her efficiency in raising me. But nothing compensated for my sex.’2

Sylvia was, in the words of her biographer Claire Harman, ‘an only child, and a girl-child, living on the fringes of a world given over to Boys.’ She grew into a tall, angular figure (much to Nora’s disappointment) who loved piano and organ lessons with her teacher, Dr Percy Buck, and aged 17 she refused to play the part of a demure upper-middle-class débutante. At ‘coming out’ balls, she only ever wanted to dance with her father, and at dinner parties she turned the conversation to theology and music, giving her views frankly. Worse, she scandalised polite Harrow-on-the Hill society by wearing ever more outrageous hats to church, including one with an enormous artificial lily on a tall stem.

Her happiest times were during the summer holidays the family spent at Ettrick in the Scottish borders, where her father fished and wrote his books, and Sylvia joined him for all-day walks over the moors. In 1914 George and Nora bought a piece of land on the edge of Dartmoor in South Devon, and began to build a house and garden there, before their bucolic dream was interrupted by the outbreak of war. George was asked to join the Foreign Office ‘on a work of national importance’, while Sylvia went to work in a munitions-making factory. Her father encouraged her to write about her experiences in a piece called ‘Behind the Firing Line’, which appeared in Blackwoods magazine in 1916, and earned her sixteen guineas.

It was the only published writing by Sylvia that her father ever saw. She was working on her first story in Dartmoor when he fell ill, and died shortly after they returned to Harrow. ‘My father died when I was twenty-two, and I was mutilated’, she wrote starkly, years later. Living with her grieving, angry mother was sheer misery, and there was no respite, even at night; Nora took it for granted that Sylvia would sleep with her, on her father’s side of the four-poster bed.

An unexpected reprieve came in 1917 when Sylvia was invited to join a group of eminent musicologists working on a publishing project on assembling, editing and publishing Elizabethan church music. Her former tutor and clandestine lover, Percy Buck (who was 22 years older than her, and married) may have had something to do with her appointment, knowing how miserable she was living with Nora. The salary of three pounds a week gave Sylvia her freedom, and instead of moving to Devon with Nora, she was able to rent a small flat of her own in Bayswater, London. ‘From time to time I felt hungry, and in winter I often felt cold,’ she recalled. ‘But I never felt poor.’

She loved everything London had to offer, and was very good at her job, visiting libraries, cathedrals and churches to gather partworks by composers including John Taverner and William Byrd. If anyone had assumed that, as a young woman with little experience, she would be happy to act as a secretary or general dogsbody, she soon put them right. As well as her paid job, Sylvia composed music and did original research into sixteenth-century notation, and she insisted on her status as co-editor of what would be a ten-volume work, Tudor Church Music. ‘I think the best we professional people can do when we find an amateur like Miss Warner’ said Percy Buck, ‘who knows far more about her subject than we do, is simply to adopt the attitude of learners.’3

In 1922 Sylvia bought a map of Essex in a sale at Whiteley’s department store, and, intrigued by the place-names (‘Old Shrill’ and ‘Sheldon Powells’), decided to take a train there on a day off from work. The mysterious marshy landscape she found at the Blackwater marsh near Southminster left her in a state of ‘solemn rapture’, she wrote, and surprised her with ‘the discovery that it was possible to write poetry.’ She also began to write a novel. ‘One line led me to another, one smooth page to the next. It was as easy as whistling,’ she recalled. ‘I told nobody. I barely told myself. I felt no obligation to go on, let alone finish.’

Her first novel, Lolly Willowes was published in 1926, and would make her famous… (to be continued in part two) Meanwhile, I love the comment below about the novel by Katherine May, which made me wonder: what novel(s) that you first read in your youth did you later re-read, and change your mind about?

Further reading

‘Surprised by joy’ on The Diaries of Sylvia Townsend Warner (Virago Classics, 1995). ‘Sylvia never stopped to ask herself why she wrote, or who she was writing for,’ he writes. ‘However, there is a clue in one of her earliest novels, where a character reflects: “One does not admire things enough: and worst of all one allows whole days to slip by without once pausing to see an object, any object, exactly as it is.”’ admires Sylvia Townsend Warner’s The Corner That Held Them; and describes her experience as a publisher of her short stories and other writings here (£).Laughter in the library

Hello and a warm welcome to this week’s edition of the Ladies’ Dining Society. It’s a mild, sunny day as I write here in Cambridge, but the leaves are changing colour rapidly and starting to twirl downwards (always hard to resist gathering those shiny new conkers/horse-chestnuts). Soon students will be returning to their colleges in the town, and some of them might even be lucky enough to study somewhere like this, below. It’s the beautiful Yates Thompson Library at Newnham College Cambridge, designed by Basil Champneys in 1897.

Thank you

That’s all from me for now. There’ll be another post about Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes soon and you can also get in touch with me directly by replying to this email. Thank you for joining our 20th century book club, and I’d love to hear your thoughts on this, or anything else you’ve enjoyed reading recently.

Quoted in Claire Harman, Sylvia Townsend Warner: A Biography (Chatto & Windus, 1989)

Sylvia Townsend Warner, Letters, ed. William Maxwell (1982), p. 251.

Quoted in Harman, p. 43.

I began reading "Rural Lives " by Harriet Baker last night, which features Sylvia Townsend Warner (she was my reason for buying it )- so this is a lovely coincidence! She is such a remarkable writer and happily I still have several of her books to read. I loved this quote, “One does not admire things enough: and worst of all one allows whole days to slip by without once pausing to see an object, any object, exactly as it is, ” - certainly one to keep! Thank you too for the Times paywall offer as I love their rereadings column and often miss it!

Loved the TLS cover! And this is great — in truth, I’ve avoided Lilly Willowes for years now on the impression that I’d find it a little dark. But this wonderful bio is causing me to rethink.