This week I’m delighted to introduce a guest post by the wonderful

, who has kindly contributed a piece about a hard-to-find place in Cambridge that combines vibrant nature and wildlife with memories of people. The Ascension Parish burial ground is maintained and made accessible thanks to the efforts of dedicated volunteers and supporters - and a few years ago Anne joined in with a work party there. This is the story of how deeply this green, magical place affected her.

Introduction

I’m Anne Thomas, a wandering American ecologist currently living and working in Grenoble, France, where the mountains are snowy and the valley is unfurling into spring. But I spent four years as a PhD student in Cambridge, England, where it was always green. In October 2020 I wrote the following essay about the graveyard where I kept company with some of the city’s élite, who happened to be underground, and the riot of green life competing with their memory.

‘The Ascension Parish burial ground (formerly St Giles’ burial ground) was opened in 1869 when the population of Cambridge, as with most Victorian cities, had grown dramatically. The parish of St Giles covered a large area to the north and west of the River Cam within which many scholars, scientists and university staff lived and worked. Thus the burial ground contains the graves of three Nobel prize winners, seven members of the Order of Merit, eight college masters, fifteen knights of the realm and thirty-nine people with entries in the Dictionary of National Biography. It is a burial place for all who lived in the Parish, of all faiths and none. These include Anglicans, Non-Conformists, Muslims, Jews, and those of many other faiths. The age span of those buried is from one hour to over 104 years.’

(from the Friends of the Ascension Parish Burial Ground website)

Green life and stone-cutting

A graveyard in England is rife with life. Even in October the churchyard is green. Soil rarely shows, shrouded by a tangle of grass in all stages of growth and senescence, leaves of so many different shapes they lose definition to human eyes. If the Friends of the Ascension Parish Burial Ground didn’t have their monthly work parties to keep the life at bay, within months, you wouldn’t know there were any dead kept and remembered here on All Souls’ Lane.

I join these work parties every month to plunge into green for its own sake and forget about work and global disasters. Today’s first task is to scrape ivy off headstones with plastic ice scrapers. It’s always a bit of a shame to strip down those early veins of deep green, but it’s easy to see the end result of their incursions on headstones that were missed the last few work parties: erasure of monuments, transforming them into topology alone. So I follow the stems down the stone, popping off each juncture of roots. I don’t try to uproot the whole endless plant. My job is only to delay.

The Parish of the Ascension church, a familiar English affair of peaked roof, rose window, and cobblestone walls, keeps humble watch over the burial ground, marking where living souls used to perform their ceremonies for the dead. The burial ground only closed to new burials in 2020, but the church has been defunct for quite a while. Now it’s repurposed as a workshop for the stonecutter, Eric Marland, who has etched out many of the more recent headstones.

Where there used to be pews—including a long narrow gap along the transept that Eric hypothesizes is where the coffin would stand during a funeral—is now a workbench, and the small chapel is cluttered with half-carved pieces of stone and tools and demonstrations of old lettering. The air is frigid, as it was designed to be, he says, to keep the bodies cold; there was no other morgue. Up on a high, deep windowsill is a painted portrait of a woman in the style of the ‘40s or ‘50s. Eric tells me it’s a painting of his aunt, who loved it here. The portrait is propped on top of a dusty box containing her ashes.

Cambridge dons and poets

The individuals in the ground outside were all notable on some level, to someone, but some have wider notoriety than others. I’ve more than once heard the quip that this graveyard holds the record for highest collective IQ, for all the Cambridge dons it contains. Ludwig Wittgenstein, the philosopher, is the most famous resident. (Eric was approached by the British Wittgenstein Society to restore Wittgenstein’s grave, and he said that doing so on film while some girls sang plainchant in the background was one of the more surreal experiences of his life.)

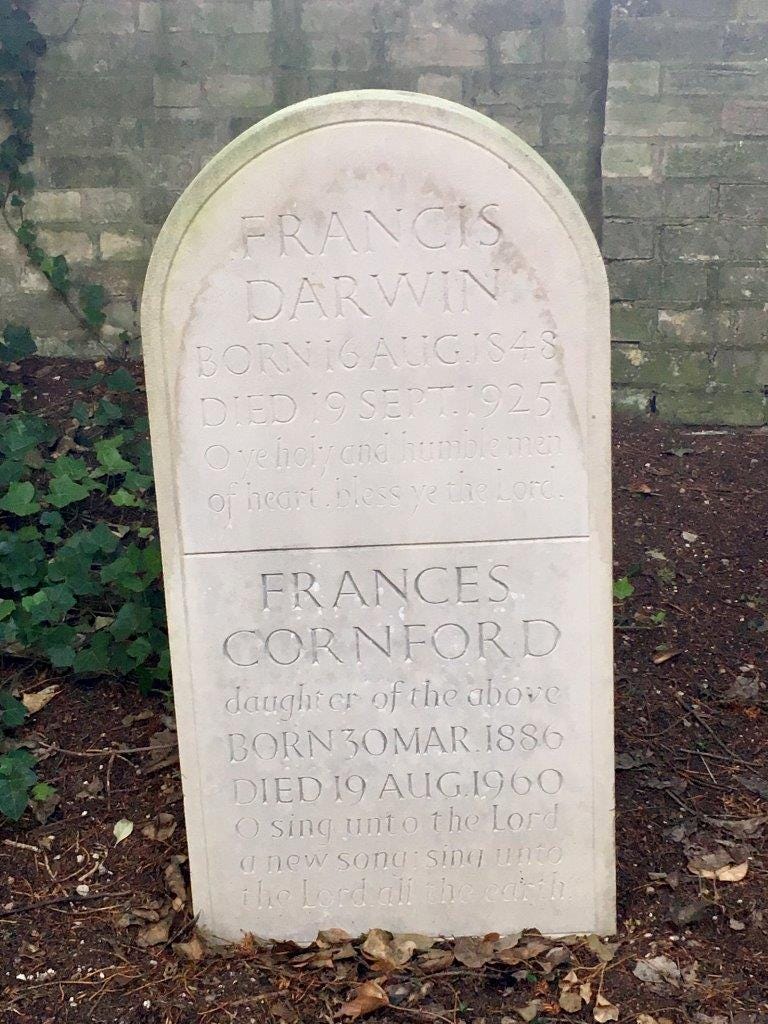

Wittgenstein is perhaps followed in fame by several of Charles Darwin’s family members: two sons, two daughters-in-law, and a granddaughter. Frances Cornford, née Darwin (1886-1960) was a poet, and Eric Marland put up a poem of hers in stone on the church wall.

All Souls’ Night

My love came back to me

Under the November tree

Shelterless and dim.

He put his hand upon my shoulder

He did not think me strange or older

Nor I, him.

Life and death

I think about life and death every time I come here, working alongside the mostly white-haired Friends of the Ascension Parish. I think about the contrast between our active party, our eager work and movement, and the silent anonymity of the people the graves are meant to mark—even the famous ones, whose lives we must continually clear of the ivy of time. I think about how soon each of our warm bodies will enter that phase of stillness.

Some grave borders have sunk partly beneath soil as the ground has shifted and as plants and their creatures make more soil. Are the bodies and coffins beneath still recognizable or have they also melted into soil? Are one hundred, two hundred years enough for this? Where is Ludwig Wittgenstein in the life cycle of this lush crust of ground? What does Frances Cornford look like now? Would she think herself strange?

I think also of war. You can find here memorials to pilots and servicemen killed in combat or accidents. In one tree-curtained corner there’s a strange, square concrete structure with rough windows. I’m told it was an anti-tank barrier, a pillbox, relict of the second world war, positioned to slow the possible onslaught of enemies bringing new death. They never came, at least not by land.

A safe haven

In the end, the most overwhelming impression is that of life. As I tear apart weft and warp of grass and rip up ivy runners, I uncover scurrying neighborhoods of pill bugs and millipedes in the damp rich soil, bright yellow snail shells with brown candy-stripes. Some headstones are held in a woody embrace of tree trunk. Brambles spread even more heartily than the ivy, sending out thick thorny ropes across the ground and plunging pink tips into the soil that burst into knots of root fiber. We use heavy shears and spades and sweat and occasionally blood to tame these.

Today, like many English graveyards, Ascension Parish Burial Ground is a wildlife reserve. Despite our shears, we want life here. The graveyard cradles diversity of life in a way the neighboring fallow field, an apparent monoculture of dandelions, doesn’t. We merely keep the graves visible, slow the overtake of brambles, and leave the wildflowers, the bird and deer habitat, the creeping things and the rich soil. We cultivate a haven for these eager lives, and for us, and for the memory of the dead.

©Anne Thomas, April 2024. All images by Anne Thomas.

I warmly recommend subscribing to Anne Thomas’s publication Anne of Green Places and you can also read some of her excellent personal essays about Cambridge on ‘The Cambridge Placebook’ here: https://thecambridgeplacebook.com/

Find out more about the history of the Ascension Parish Burial Ground, and how to join its working parties here: https://ascensionparishburialground.uk

Wikipedia has a list of the people buried there and suggestions for further reading here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ascension_Parish_Burial_Ground

Next time on Lost in the Archives: books about Cambridge and the results of last week’s mini-survey (still time to add your thoughts below!). Thanks for all your feedback and your excellent comments.

Poignant. My mum’s funeral/memorial service is this Friday. 🌿✨

A lovely little graveyard. Would like to hear more about who is buried there