The Cambridge 'Masters' Wives Quilt'

Carolyn Ferguson on a detective story and a mystery

I’m delighted to publish a guest post this week by textile historian Carolyn Ferguson, who has done brilliant original research on a rare embroidered coverlet from 1892. The ‘Masters’ Wives Quilt’ is currently on display at the Museum of Cambridge as part of a free exhibition, The Stories Behind the Stitches, from 27 March -23 September 2024, exploring wellness, disability and self-expression through Cambridge textiles.

In 1985 an important piece of Cambridge history came up for auction in London, Carolyn Ferguson writes. It was not a written document, painting or a piece of pottery, but a textile that had been given the moniker ‘Masters’ Wives Quilt’. In 2012 the Museum of Cambridge acquired it (Museum of Cambridge Collection: 1.2014). An embroidered ‘1892’ suggested a likely date but who made this textile, and why, remained a mystery. As an inveterate quilt and fabric researcher I have been lucky enough to be able to study this historic textile closely during the past eight years. Along the way there have been many red herrings and blind alleys; it has been quite a journey, involving both hard graft and incredible good luck.

The so-called ‘Masters’ Wives Quilt’ is an embroidered coverlet with a chequerboard design of alternate 'Turkey red' and white blocks. There was no provenance to support the name of this textile, other than scant information from the seller’s family, but it clearly belongs to the genre of ‘signature quilts’ where individual blocks have multiple names or initials that are written with ink or stamped or embroidered on to the fabrics in some way. Signature quilts form important primary historical documents that give insights into communities, neighbourhood groups, relationships, family history and important historical events. They were made either for fund-raising or for commemorative purposes, and in the UK the heyday of production was the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The ‘Masters’ Wives Quilt’ differs from the signature quilt norm as each block has an embroidered motif and/or initials. I have studied the iconography of each of its 475 embroidered blocks, about half of which have initials as well as stitched motifs, and I now believe that there were more than 200 individual stitchers - a much larger group than the 13 or so Cambridge Master’s Wives that existed in 1892! I have discovered that the quilt's makers also included wives of Fellows and other University employees and town dignitaries, as well as women members of charitable organisations and neighbourhood and friendship groups. In addition there are initials of children.

What clues can be found in the individual blocks? 55% of them illustrate the Victorian love of flowers.

Their content is, as we might expect, symbolic; there are daisy motifs representing the innocence of young love (and also the floral emblem for Girton College); ivy for fidelity and marriage; tulips for romantic love; corn to give riches and fertility and pomegranates for fertility and marriage. As an emblem of the Christian Church pomegranates represent hope for eternal life; in the near East, the abundance of seeds gives it the meaning of fertility.

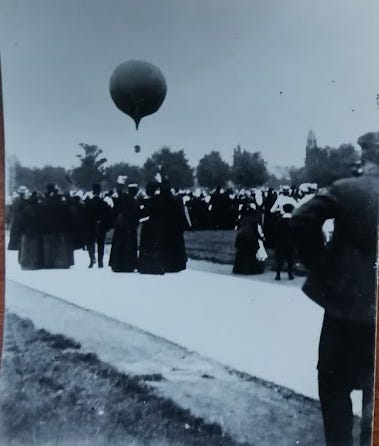

Birds and animals also feature; love-birds, swallows, swans and storks all echo the sentiments of love, good fortune and fertility. Horse-shoe blocks suggest good luck wishes, and there are blocks that show 1890s fashions in sporting pastimes and motifs from oriental china and fans. There are also national flags for the US and Germany, religious symbols, Cambridge college crests and symbols and hot air balloons.

Many people do not know that Cambridge has a history of ballooning. 1829 saw the first balloon ascent in Cambridge, from the Seven Sisters Brewery in Newmarket Road. Thereafter this became an annual event. At Queen Victoria’s Coronation celebration, on Parker’s Piece in 1839, some 30,000 people saw a balloon ascent by Britain’s most famous balloonist, a Mr Green. This ascent cost 70 guineas - about £6000 today - and so was clearly very special. A balloon ascent also featured at the public festivities to celebrate the wedding on Prince George, later King George and Princess May (Mary of Teck) in July 1893.

It seems likely that this ‘Masters’ Wives Quilt’ of 1892 was made to celebrate a wedding, and that given that the quilt's makers were important people from Cambridge town and gown, this wedding must have been significant.

Two blocks offer important clues: one containing an obscure Welsh runic alphabet and another, poorly executed block of a slightly different colour, with a simple chain stitch cross. It’s likely that this ‘cross’ block was a replacement for an earlier one identifying the recipients. This suggests that the wedding never took place, as it would have been bad luck to keep the couple’s initials in place.

There is a further vital clue in the Welsh runic block (see below), which follows the 'Coelbren Y Bierdd' or Welsh Bardic alphabet. The words ‘duw a digon’, translate as 'God is enough' or 'God and Plenty'. Additionally this block has the initials, ‘m’ and ‘e’ above the runic letters and the initials AWT below. The top initials might represent ‘m’ for Princess May (Mary of Teck) and ‘e’ for Eddy, the name by which Prince Victor Albert of Wales, Duke of Clarence was commonly known.

At the time of their engagement in early December 1891, Prince Albert Victor was second in line to the throne and would have become Prince of Wales after the death of Queen Victoria. The Welsh motto has a royal connection, for the National Trust collection has a George V Jubilee mug of 1935 showing a picture of the King and Queen with a ‘duw a digon’ inscription.

I suggest that the quilt was made as a wedding gift by the Royal Borough of Cambridge for the royal marriage between Prince Victor Albert and Princess May (Mary) of Teck, due to take place on 27 February 1892.

After the engagement was announced, committees were set up in December 1891 by societies, royal boroughs and masonic lodges across Britain, all keen to contribute to impressive wedding gifts. As we know, this royal marriage never took place because the Prince tragically died of influenza some weeks before the wedding date.

You might say that the time between the news of the royal engagement and the projected wedding was too short to complete such a detailed quilt in Cambridge. However, given the timing of the engagement in just such a pandemic (then ‘Russian flu’) as the world experienced in 2020-21, perhaps the women who made it were at home trying to amuse their children and needed a creative outlet. You, the reader, must make up your mind as to whether my argument is convincing or not.

© Text and photographs by Carolyn Ferguson (all rights reserved). This blogpost was first published on Ann Kennedy Smith’s Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society Wordpress blog on 14 April 2020. Carolyn Ferguson's publications include ‘A weave of words: fabric print and pattern in mid-nineteenth-century women’s writing’ in Fashion and Material culture in Victorian Fiction and Periodicals ed. Janine Hatter and Nickianne Moody, Edward Everett Root, 2019, p 67 - 85.

There are so many stories behind stitches. I've done every form of textile work. Because the labor takes time, stories evolve. The original goal can end or change. The skills of the artist can improve. Sometimes there is a break in the endeavor, in my case, a decade sometimes. During that time, my interest and patience waned. I've knitted cancer caps for a person who chose to not suffer chemo and thus did not need caps. I embroidered countless patches in the 70s for CB-loving friends of my parents. I've spent years making lavish needlepoint pillows with the focus of a Victorian lady. But I've never been a quilter. I love the modern op-art quilts made by today's contemporary artists. But I most poignantly remember the mothers and lovers carrying their hand made squares down Christopher St, New York City, in 1988 with bearers carrying a candle beside them. Everyone was crying, remembering the person who had inspired their square. Stories and textiles. Powerful stuff.

What a fascinating object, and a fascinating - and convincing - theory.