'What women I met! What fights I joined!'

A Bohemian women's club in Greenwich Village

Hello, and welcome to Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society. I’m on my travels at the moment, so here’s my review of a book I enjoyed a couple of years ago. Speaking of reading for pleasure (and work)

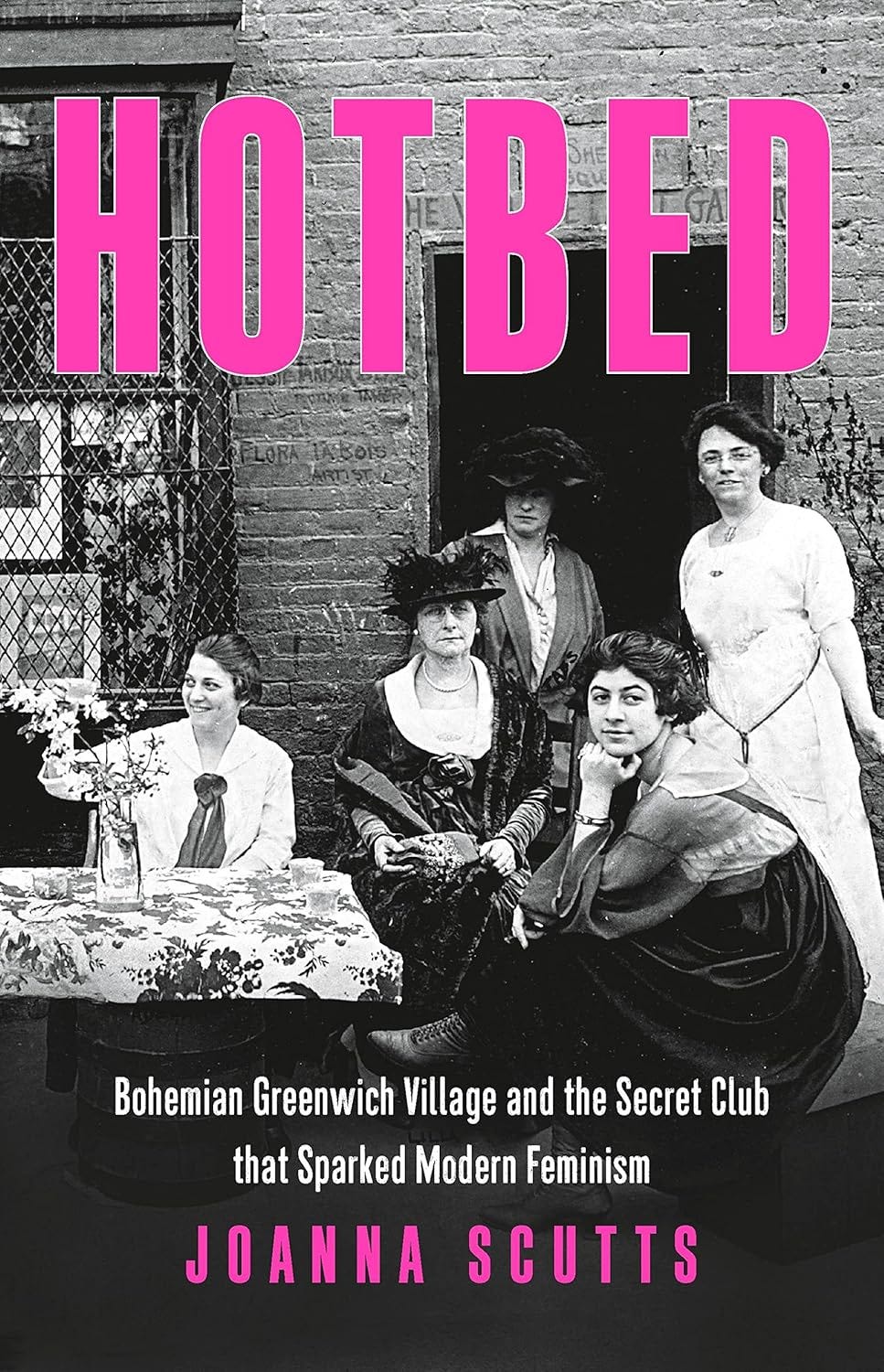

’s ‘How to read and why’ made me think about why we choose to read books in the way that we do, and ways in which that habit changes over our lifetimes. So this week I’d love to hear more about what you’ve been reading recently, and what you’re enjoying about it.Joanna Scutts Hotbed: Bohemian New York and the secret club that sparked modern feminism (Seal Press 2022 in USA; Duckworth paperback in UK, 2023).

For middle-class bohemians in New York before the First World War, Greenwich Village was the place to be. The attraction of this part of Manhattan was the “contagious buzz” of new ideas about how to live and love: the Washington Square Bookshop, which opened in 1913, had a “complete shelf of Psychoanalysis and the Psychology of Sex”, and the new Freudian vocabulary lent spice to conversations in Russian-themed tearooms and basement restaurants. When Vassar-educated poet Edna St. Vincent Millay and her younger sister Norma moved into the neighbourhood, they worked hard to learn the local language. “We sat darning socks on Waverly Place and practiced the use of profanity as we stitched”, Norma recalled. “Needle in, shit. Needle out, piss. Needle in, fuck”.

Another shocking new word was “feminism”. Newspapers poured scorn on it for implying everything they feared: non-motherhood, free love, easy divorce and economic independence for women. “The implication”, as the journalist Rheta Childe Dorr put it, was that feminism was “something with dynamite in it”.

Childe Dorr was one of the early members of Heterodoxy, a debating society for women founded in Greenwich Village in 1912, and the subject of Joanna Scutts’s Hotbed: Bohemian New York and the secret club that sparked modern feminism. This enlightening book covers the first ten or so years of the club’s existence. It is also the story of the early feminist movement in the US, and highlights the under-acknowledged part that these activist women played in psychology, education, theatre, journalism, anti-lynching legislation and the early-twentieth-century American labour movement.

"What women I met! What fights I joined! How many speeches I made!," Inez Irwin recalled. "But best of all – what women I met!"

The Heterodoxy club was the brainchild of Marie Jenney Howe, a former Unitarian preacher from Des Moines who declared herself a “disciple” of Charlotte Perkins Gilman after reading her Women and Economics (1898). After moving to New York in 1910 Howe became an organizer in the newly revived suffrage movement, and the club she founded two years later included “Democrats, Republicans, Prohibitionists, socialists, anarchists, liberals and radicals of all opinions” as well as Gilman herself. In 1914 the group was the subject of an exposé by the New York Tribune, which described it as “a de facto star chamber council of the prominent women of New York” – but, according to the arts patron Mabel Dodge Luhan, they were simply “women who did things, and did them openly”.

The club itself did not aim to “do” anything apart from meet in a no-frills Village restaurant on alternate Saturday afternoons, with a topic of discussion agreed in advance. To give each other space “to doubt and to disagree”, members kept no records; guest speakers included the poet Amy Lowell and the founder of Planned Parenthood, Margaret Sanger, while Emma Goldman gave a talk on anarchy. “We thought we covered the whole field,” one member recalled, “but really we discussed ourselves.”

The Heterodoxy women did more than that, of course, and much of the action of the book takes place away from the club itself. When, in 1913, a weavers’ strike began in Paterson, New Jersey, the International Workers of the World union stepped in and club member Elizabeth Gurley Flynn organized street meetings, co-ordinated stop-work protests, called out police brutality and helped to expose the silk industry’s exploitation of teenage girls.

The causes of suffrage and labour rights were allied in 1910s New York, where protests, fundraisers and rallies kept both issues in the news. When the glamorous lawyer and suffragist Inez Milholland was photographed wearing an evening gown alongside textile workers on a picket line, the headline in the New York Times was “Inez Milholland Helping”. She knew the vote-winning value of a photo opportunity. In 1913 she led the National American Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington DC on a white horse, while wearing a crown and flowing cape.

There were other, less visible campaigns. In 1914 a high-school teacher, Henrietta Rodman, challenged the New York school board on its “don’t ask, don’t tell” strategy requiring women teachers to hide the fact that they were married. And in the late 1910s campaigning for access to birth control, especially for working-class mothers, became an important focus of Heterodoxy’s activism.

The concerns of the mostly middle-class and well-educated Heterodites resonated differently among the less privileged. Rose Pastor Stokes was born into a poor Jewish family in the Russian empire and brought up in the East End of London. When her family moved to Ohio she worked in a cigar factory for eleven years before becoming a journalist. Her move to New York and marriage to a Madison Avenue millionaire did not stop her activism, and in 1912 she led a strike by the city’s hotel and restaurant workers. But when she asked one strike-breaker why she hadn’t joined the union, the woman looked straight at her and pointedly replied: “I’m in hopes that some rich man will come along and marry me”.

Socialists and feminists were equally guilty of overlooking racial injustice, Scutts notes, as can be seen in the distance between Heterodoxy’s white bohemians and their Black counterparts. Club member Ida Rauh, who helped found the Provincetown Players in 1915, took a stand when she refused to cast white actors in “blackface” for Eugene O’Neill’s The Dreamy Kid (1919), but Grace Nail Johnson, who promoted anti-lynching legislation and later became prominent in the Harlem Renaissance movement, was the club’s only African-American member. The group’s acceptance of her had undertones of unconscious prejudice. “You were today elected to the Heterodoxy with real enthusiasm”, Howe told her, “so do be a good girl and come regularly and be responsive.”

The First World War demanded that Heterodites take sides. Those who were for “a woman’s war against war”, as Dodge Luhan put it, found themselves pitted against pro-war patriots like Gilman, who resigned from the club in protest at her pacifist sisters’ views. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and America’s entry into the war severely tested Heterodoxy’s founding principle – the right to speak one’s mind. “One could talk about anything, anything!”, Scutts says. “One could be convicted of anything (anything!) too.”

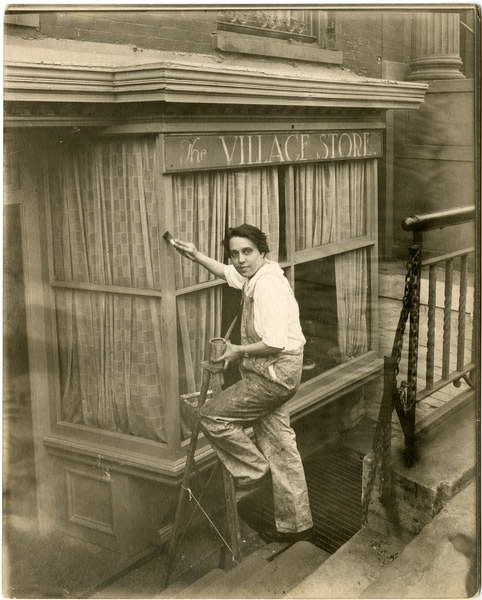

There was an attack on another front after the war, as Greenwich Village became a tourist attraction. A series of postcard photographs taken by Jessie Tarbox Beals promoted the quaintness of Village life, the drinking dens, antique shops and colourful characters. Nonconformist and transgressive elements associated with the area were scrubbed from the record.

Hotbed is a vibrant and engaging account of female autonomy in the early twentieth century. As Joanna Scutts admits, the history of a long-running club can be an unwieldy subject. But the stories come vividly to life nonetheless, and their continuing relevance is not in doubt: the anti-lynching legislation that Grace Nail Johnson called for a hundred years ago was signed into law in March 2022 as the long-delayed Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act, and the courage of Heterodoxy’s Mary Ware Dennett is even more impressive in the light of the overturning of Roe vs Wade. Under continual threat of imprisonment, she refused to stop distributing her sex-positive educational pamphlet “The Sex Side of Life” through the US Postal Service. The struggle to enlighten is far from over.

Thanks for reading this, a longer version of my review first published in the Times Literary Supplement here. I would love to hear your thoughts about this club, or other friendships and alliances from history that have inspired you, and what books you would recommend about them (I loved Daisy Hay’s group biography about Joseph Johnson’s dining club, see my post below). There was a fantastic response to my post on Dorothy L. Sayers at Oxford last week, with some truly excellent comments. But if you just want to sit and quietly ruminate, like these gentle creatures, that’s fine too.

Joseph Johnson's modern dining club

In late 18th century London there was a little-known, but influential, dining club for writers, artists, political thinkers and scientists hosted by publisher and patron of the arts, Joseph Johnson. He is the subject of biographer Daisy Hay’s new book,

When you’re shaking up the world, you need a tribe. These women were shaking the world about 50 years before my adolescence—not so long, really—and I had never heard of them. Some of their names and deeds are still new.

Thank you for reposting this, Ann. Like Hilary, I read the Millay series in the New York Times, and realized how little I know about her life and her work. I didn’t know about the shameful delay in passing the Emmett Till law, or its origins. I appreciate how much you’ve given me here, sending me in the right direction.