Hello! And welcome. Last month I wrote about the water-reflecting presence of Gwen Raverat’s house by the river at the beginning and end of her life. My ‘circular’ post was in part inspired by thinking about her ‘Cambridge Upper River’ painting above, and one of my readers asked some perceptive questions: ‘Is the time of year spring or autumn? What do those hints of dark red on the branches of the tree suggest? If Gwen was painting what she saw in 1955, why (alas!) has she not painted the punt more accurately?’ It seems likely that Raverat added the punt from memory — and perhaps she didn’t mind that it wasn’t a very realistic image. I wanted to write something about the late-life circumstances in which she painted this, and other lovely views of the River Cam near her home.

Gwen Raverat's House by the River

‘This is a circular book,’ the artist Gwen Raverat, aged 62, explains at the start of her memoir Period Piece. It was her first book and she had wondered how to structure it, until she decided on the idea of thinking of it as like the wheel of a bicycle.

Raverat’s river paintings

After she finished writing her memoir Period Piece, published to great acclaim in 1952, 61-year-old artist Gwen Raverat suffered a stroke that left her paralysed on one side. She could no longer practice her wood-engraving but it was still possible for her to paint, so she continued to work on views of the mill-pond from the balcony of her riverside home, the Old Granary. Occasionally she asked to be taken in her wheelchair to the Backs or Coe Fen , ‘and left with a whistle round her neck for attracting attention, if needed, and there she painted for hours on end, often with cows looking over her shoulder’ writes Frances Spalding in her wonderful biography, Gwen Raverat: Friends, Family and Affections (Penguin paperback, 2021).

But after a second, even more debilitating stroke in 1955, Raverat’s daily practice of painting became increasingly difficult, until - thanks to a new drug recommended by the neuroscientist Horace Barlow (the youngest son of her first cousin Nora Barlow) - Gwen’s painful spasms were reduced, and she was able continue to paint outdoors whenever the weather permitted.

Seeing this photograph of Raverat below, in her shapeless black ‘curate’s hat’, peacefully painting on the Cambridge meadows near her riverside home seems in keeping with her ‘impassioned belief in life, existence and the beauty of the world.’ What a gift it was that the affection and support of her family and friends - along with progressive medicine - gave her during this last part of her life.

As Frances Spalding writes so beautifully, by writing Period Piece, still loved by so many readers, ‘Gwen had discovered by coming home, returning to the past and carrying it into the present, she had brought her life full circle’. The same might be said of her painting these peaceful riverside views, still much the same as the river beside which she played with her young Darwin cousins in the late nineteenth century.

The Cam in winter

Below is my photograph of the River Cam (from a different vantage point) taken in mid-January 2024: The sign ‘LEARN TO ROW’ on a college boathouse near my home seemed particularly apt last week, as the swollen river lapped ever closer to the boathouses’ steps. What better time might there be to have a boat, I thought to myself. Irony upon irony: due to the high level of the river, no rowing (or indeed punting) was possible until the floods subsided and boats and landing stages were accessible once again.

I’m pleased to report that the water level has receded this week, and it was very nice to see rowers back in force in Cambridge on this cold and sunny Saturday morning.

This week’s reading suggestions:

These illuminating insights by Sarah Harkness into the married life of Emily, Lady Tennyson: ‘There weren’t many great opportunities for women in Victorian England, and I choose to assume that at the age of thirty-seven, Emily Sellwood was quite capable of choosing the best and most interesting life she could.’

A thought-provoking joint post ‘How to live with three languages daily’ by Elin Petronella and Remy Bazerque: ‘To manage your own multi-lingual reality is one thing. To do so while parenting is yet another mind-blowing reality.’ This struck a chord with me, thinking about my own father Joe’s enduring love of the Irish language, particularly the poetry he learned by heart as a schoolboy.

Mary Roblyn’s amicable question, Who are the people in my neighbourhood? inspired by gatherings outdoors during the Covid pandemic: ‘People showed up. They continue to show up. They bring friends, family members, pets, house guests, and visiting scholars. Actually, we’re all visiting scholars. We read a lot of books.’ I am very glad that Mary and I are part of one another’s virtual neighbourhood here on Substack.

Paid subscribers really do help me to keep this newsletter afloat (no pun intended) so if you value this space and can afford to do so, I encourage you to upgrade. Thanks so much for reading and sharing, and as ever, I would love to hear your comments and thoughts.

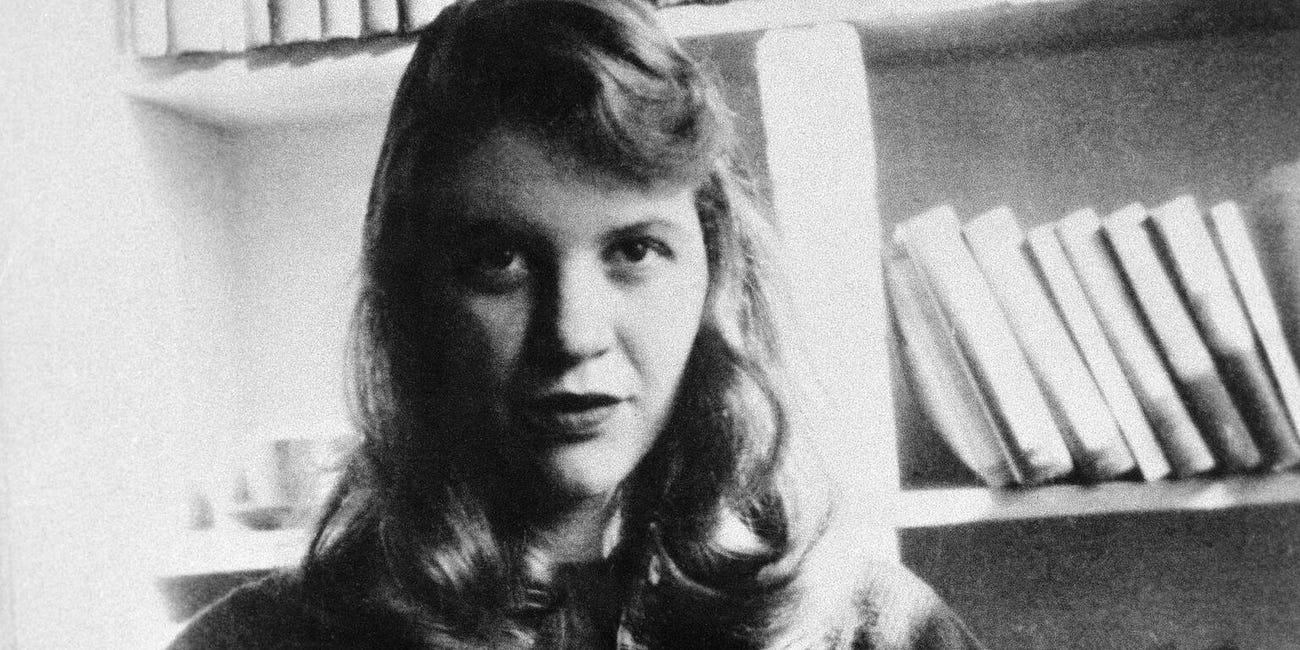

Sylvia Plath at Home

‘On Dec. 7th a new life will begin,’ Sylvia Plath confidently wrote in a letter home to her mother in Massachusetts. December 7th 1956 was when Cambridge University’s Michaelmas term ended, and the date that Plath, who until then had been in student halls, officially moved into her first marr…

I got chills from Raverat's determination to make art despite her stroke. It also reminds me to sit in gratitude and more importantly, do the work! Glad I found you here Ann!

I loved this glimpse of Raverat in her creative and determined old age. As a childhood reader of Lucy Boston, I look forward to rekindling memories here.