‘Lock up your libraries if you like; but there is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind.’

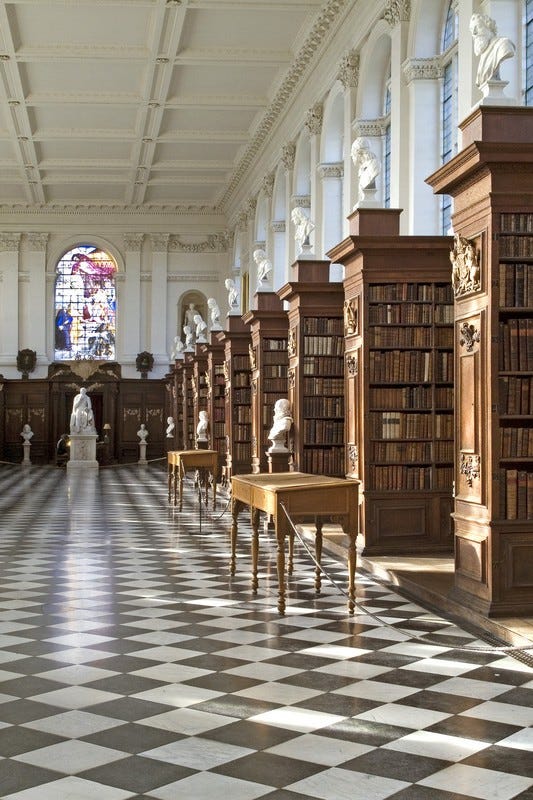

Virginia Woolf’s glorious declaration of intellectual freedom in A Room of One’s Own (1929) was the result of her female protagonist being prevented from entering the 17th-century Wren Library at Trinity College Cambridge (she calls it ‘an Oxbridge college’ in her book, but it’s easily identifiable). Woolf drew inspiration from her 1928 visit to Cambridge to give a lecture at the two women’s colleges.

This post is about two of the college libraries that were open to women students from the beginning, and are now among Cambridge’s best-stocked reading spaces, accessible to anyone with a reader’s ticket.

The right to read

When Cambridge University’s first two colleges for women, Girton and Newnham, opened their doors (in 1869 and 1871 respectively), they offered their students a ‘room of their own’ in which to live and study away from their families. ‘How much more effectually, & with how much less mental strain, a woman can study,’ Anne Jemima Clough, the first principal of Newnham College, wrote, ‘where all the arrangements of the house are made to suit the hours of study, — where she can have undisturbed possession of one room, — and where she can have access to any books that she may need.’1

Having the right to read books in a library, even in a place like Cambridge, was not something that could be taken for granted in Victorian times. From the beginning, female students, lecturers, scholars and scientists at Cambridge had only limited access to most of the university’s libraries, lecture halls and laboratories because as women, they were not permiited to be members of the university.

By the 1890s, as male undergraduate numbers grew, there was increasing demand on these privileged spaces and the women were edged out even further. Some male academics refused to allow female students into their lectures and laboratories. Distinguished women scholars had no automatic right to enter the University Library (even though some of the scholarly books and academic papers they had written and co-authored with male colleagues were stocked there). By 1897, the same year as the mass protest against Cambridge women students being given degrees, access to the library by ‘non-members’ (= men who were not members of the university, and women lecturers, scholars and scientists) was reduced to a meagre two hours a day.2

A reading room of their own

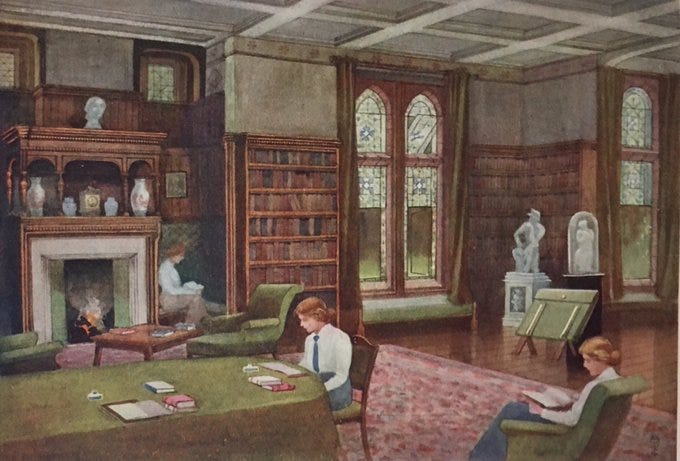

The answer for the women’s colleges was to build, not just residential and dining halls for their students, but well-stocked libraries of their own. To do this, they needed donations from members of the public. Tennyson, Ruskin and George Eliot were early supporters of Girton, and gave valuable gifts of books as well as money. Henrietta, Lady Stanley of Alderley (1807–1895) gave £1,000 towards the first Library, which was named after her in 1895. E. E. Constance Jones, Girton librarian from 1890 to 1893, recollected that ‘The library was to a great extent a lending library for the students, and the fine room which contained the bulk of our books at that time - the Stanley Library - was much frequented as a reading-room.’3 (Above is a painting of students at work there. Note the large shared table in the middle.)

That room, with its beautiful stained-glass windows, is still there today, but in the 1930s, a bigger library was required to cope with Girton College’s increasing numbers of students and book collections, and the beautiful McMorran Library, with its awe-inspiring vaulted timber ceiling (see my photo below) was built. It has been expanded with a multi-award winning modern extension, and with over 95,000 books it’s still one of the largest, and arguably most-loved, libraries in the university.

(more here about Newnham College’s Yates-Thompson Library which opened in 1897… meanwhile, here’s a tiny peek at its amazing vaulted ceiling.)

Not Afraid of Virginia Woolf

In 1928, a twenty-year-old student called Elsie Phare (later known as E.E. Duncan-Jones) wrote to Virginia Woolf, inviting her to give a talk on the subject of women and fiction to the Arts Society at Newnham College, Cambridge. The society’s president Elsie Phare was in her second year studying English Literature, so it must have been thrilling when one of the great modernist writers of the time provisionally accepted the invitation (the following year T.S. Eliot politely turned her down). The success of Virginia Woolf’s

Five things to read (outside the library)

This month I loved "Hey, Can You Read This for Me?" by

, about the tricky subject of asking others to comment on your writing, and (on the subject of etiquette) the dos-and-don’ts of family gatherings, with sound advice from Shakespeare, Austen and the Brothers Grimm, brought to you (just a little tongue-in-cheek) by the well-read .I was intrigued to read

’s two-part post on ‘The character assassination of Alison Uttley’ - why did the author of the Little Grey Rabbit stories attract such criticism? - and ’s ‘What's got my attention this week #52’ was a great pleasure to read, stuffed with so many brilliant suggestions, and I was thrilled to find my piece on ‘manless climbing’ and the great Dorothy Pilley included.And if mid-June happens to be inclement where you are, I recommend plunging into

’s blissfully balmy ‘Summer Collection’ of paintings on Beyond Bloomsbury.

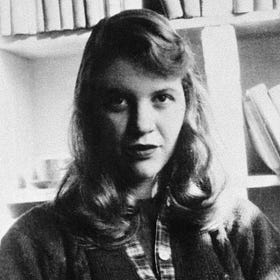

Coming up this June: Sylvia Plath and more

Next Sunday June 16th is Bloomsday, and I’ll be publishing my double post on the ‘lost’ wedding photographs of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. Don’t miss it - it’s the first of my new series of special monthly posts for paid subscribers. Meanwhile I hope you have as happy a time as this lady at The Orchard in Grantchester last Sunday, above, reading with her very patient canine friend. (It’s not exactly warm in this corner of England, but it is the perfect weather for reading outdoors, and there are no wasps on the jam yet.)

Sylvia Plath at Home

‘On Dec. 7th a new life will begin,’ Sylvia Plath confidently wrote in a letter home to her mother in Massachusetts. December 7th 1956 was when Cambridge University’s Michaelmas term ended, and the date that Plath, who until then had been in student halls, officially moved into her first married accommodation. ‘Home’ for the next six months would be a rented flat at

Finally, over to you

Thank you so much for reading, and I’d love to read your comments, if so inclined. Here’s what I’d like to know this month:

Is there a novel or story you particularly associate with summer?

What library from childhood (or older!) is especially memorable for you?

If it’s not an impertinent question, where do you enjoy most enjoy reading?

If funds allow, I hope you might consider upgrading to a paid subscription for Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society - and join this friendly community for book club discussions, chat threads and more.

A talk given in 1874, quoted in Gillian Sutherland, Faith, Duty and the Power of Mind: The Cloughs and their Circle 1820–1960 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 99.

‘In this paper, I explore the admission of women readers in greater detail and examine how the control of access to (male) privileged spaces such as the University Library (alongside lecture halls and laboratories) was bound up with and symbolic of the status of women in the university.’ Jill Whitelock, ‘"Lock up your libraries"? Women readers at Cambridge University Library, 1855–1923’ in Library & Information History, Volume 38 Issue 1, Page 1-22, ISSN 1758-3489.

Summer reads - JL Carr's A Month in the Country and Swallows & Amazons.

Summer read: AS Byatt's Virgin in the Garden is a wonderful 1950s summer memory. Also The Go-between...and most recently, Ann Patchett's Tom Lake. Favourite place to read...on a lounger, by a pool, with a glass of wine!