Welcome to Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society, exploring hidden corners of literature and bringing forgotten women’s stories into the light. This week’s post is about a little-known but influential businesswoman in Victorian Cambridge. In the late nineteenth century, ‘separate spheres’ for men and women, together with the class system, in the UK usually meant gendered employment: a middle-class woman might be a governess or lady's companion, while her working-class sister might run a haberdashery business. It is hard to find exactly how many Victorian women were in charge of traditionally male businesses, but they were nevertheless active. Here’s one story I uncovered.

‘British historians have made extensive use of city and state trade directories, censuses and the records of insurance companies to try to track down women in business… All sources hide a number of women in business. Married women’s business in particular is very often attributed to their husbands – or simply invisible.’ Women and Business since 1500 Béatrice Craig (Palgrave 2016, pp. 98-99)

‘L. Greef’, painter

Florence Ada Keynes (née Brown) had happy memories of her time as one of Newnham College’s first cohorts of students from 1878 to 1881. In By-ways of Cambridge History (1947) she captures the prevailing fashion for Pre-Raphaelite art and colourful interior decoration:

‘Newnham caught the fever. We trailed about in clinging robes of peacock blue, terra-cotta red, sage green or orange, feeling very brave and thoroughly enjoying the sensation it caused.’ (p.x)

In her second memoir, Gathering Up the Threads: A study in family biography (1950) Florence recalls how, as a young wife and mother still living in Cambridge, she and her family were amused by the names of ‘Greef’, ‘Sadd’ and ‘Pain’ over the shops in King’s Parade.

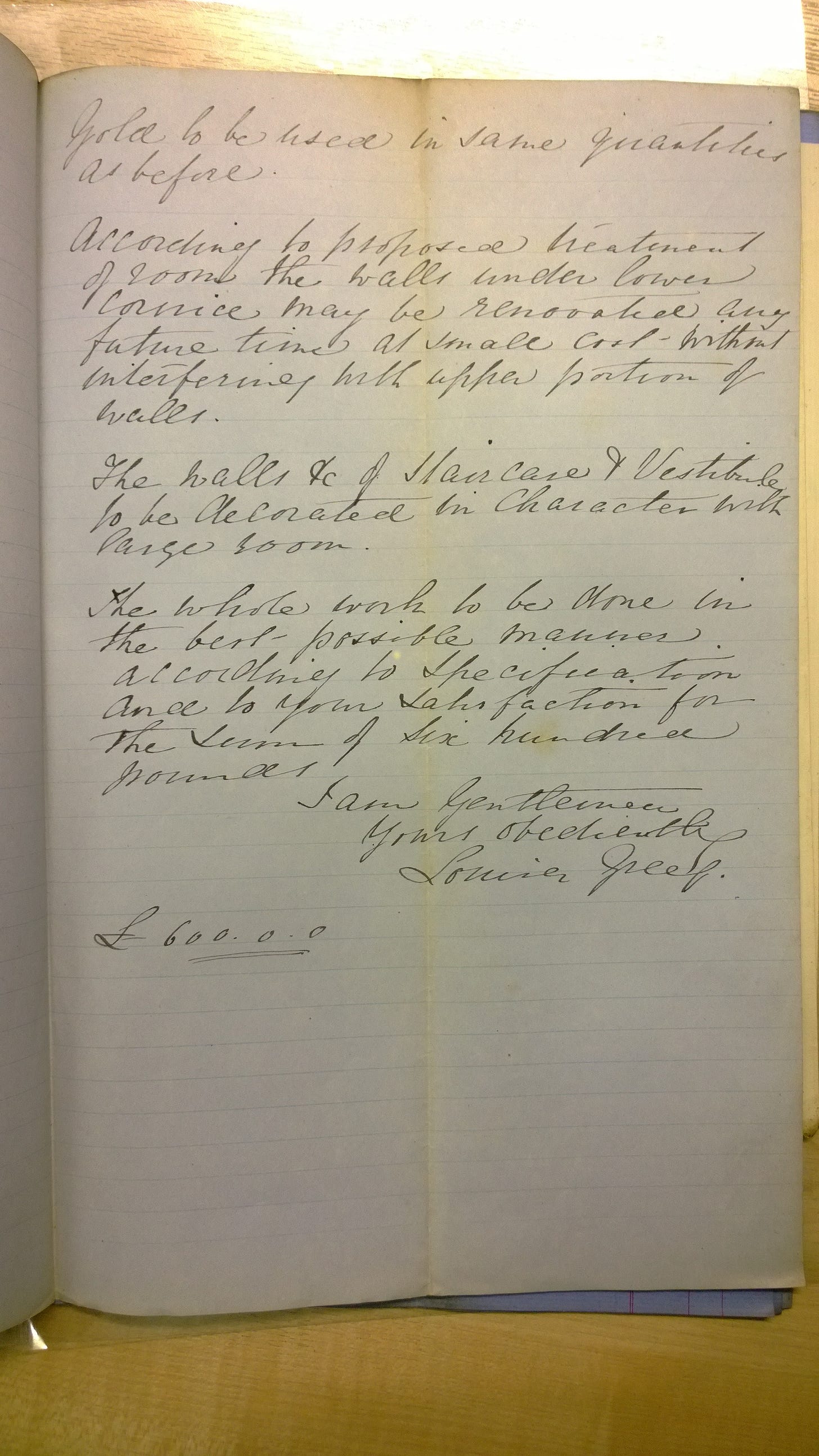

A few years ago, as part of my research into pioneering women students, workers and university wives at Cambridge, I was looking through Newnham College archive account books from the 1880s when the name ‘Greef’ caught my eye. There was a carefully written note of a payment made by the fledgling women’s college to ‘L. Greef, painter’, and I assumed that this referred to a male painter and decorator.

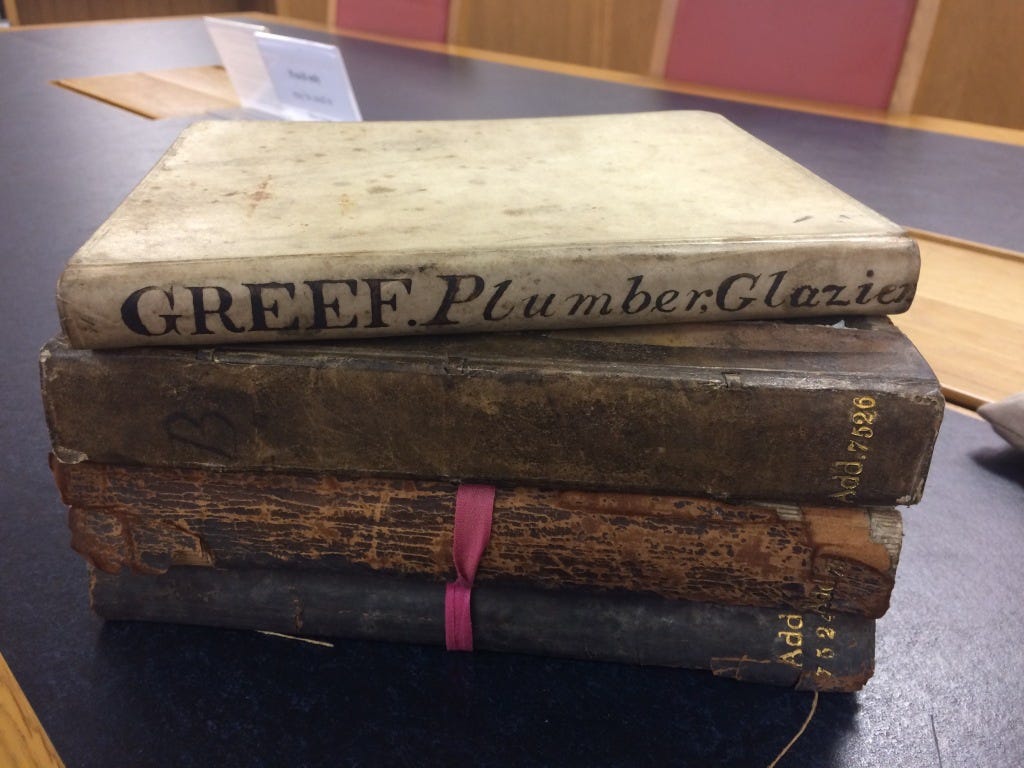

After further research, including consulting the Greef company’s substantial account books dating back to 1798 (held in the Manuscripts Room at Cambridge University Library),1 I discovered to my surprise that L. Greef was Louisa, and that she was the boss. In the late 1870s she had taken charge of the long-established family business that had provided plumbing and glazing services to the Cambridge colleges for over a hundred years, and she took on the challenge of steering the firm in an ambitious new direction: painting and interior decorating. So while Florence Keynes and her student friends were drifting around in colourful dresses (and studying hard too, of course), Louisa Greef was busily building up her firm and finding work in university properties, public buildings and the private houses that were springing up in the suburbs of the town.

The Greef household

Louisa Headdey was born in Cambridge in 1829, the fourth and youngest child of William Headdey, a butler at Clare Hall (now Clare College) and Elizabeth Headdey (1807-1887). She married Robert Greef at All Saints’ Church in 1863 and moved into his family home at 4 King's Parade (depicted in the painting above), over the shop that Florence Ada Keynes remembered. Robert Greef had inherited the long-established family business, and their house was situated between that of John Swan, a retired bootmaker and his wife, and Mary Careless, a bedmaker with her five student lodgers.

The Greef household included Louisa's mother Elizabeth Headdey (listed in the census as an ‘assistant’), three undergraduate lodgers and a cook and housemaid. Robert and Louisa's only child, Louisa Ellen Greef, was born in 1864 but sadly died just a few weeks later. (The family grave is in Mill Road Cemetery, and there is more information about the Greefs on their excellent website).

In the 1871 census Robert Greef was listed as a ‘Plumber Master employing 10 men’. A year later the household had been joined by two young Headdey relatives who became the Greef firm’s newest employees: Louisa's 17 year old nephew Arthur Headdey (the son of her brother William) who came to work as a trainee accountant, and his younger cousin Henry Edward Fuller (the son of Louisa's sister Elizabeth Fuller) who started work as an apprentice plumber.

Louisa’s ambitions

When Robert died in 1876, aged just 43, Louisa took charge. It was not unknown for a widow to take over the family business in this way (for other enterprising women, see Lizzie Broadbent’s Women Who Meant Business blog). After Robert’s own father died in 1838, his mother Ann ran the business while bringing up three children, and Louisa’s sister Elizabeth Fuller, also a widow, had been running her husband’s bakery and brewery business at 45 Sidney Street since 1869. Elizabeth’s children, including Henry, had done well: her older son was now working as a college cook and her daughter Annie was a music governess.

With the help of her two young nephews, Louisa began to expand the Greef business. According to the 1881 census, she was employing thirty men, which means that in the five years since she was in charge, the company's size had tripled. This was probably due to her decision to move into the lucrative area of painting and decorating, in response to the growing demands of domestic customers in the family houses being built up around Cambridge in the 1880s, after Fellows were permitted to marry in 1882. As it happens, one of those houses belonged to the newly married Florence Ada and her academic economist husband (John) Neville Keynes: they bought a large, newly built villa on Harvey Road, moved in while the paint was not yet dry and raised their three children there.

From the beginning, Louisa Greef had ambitions for her growing company: 'L. Greef, Plumber, Glazier, Plain & Decorative Painter and Paperhanger' was advertised in Spalding's Almanack stating that they offered a range of services for 'Public and Private Buildings'. In 1882 Greef was one of three companies to tender a quotation to refurbish the old Guildhall. Unfortunately for her, the contract went to F. R. Leach instead; already well known for his work in decorating churches, grand houses and civic buildings all over England, he had recently opened an elegant shop and showroom at 3 St Mary’s Passage in the centre of Cambridge.

Chasing twopences

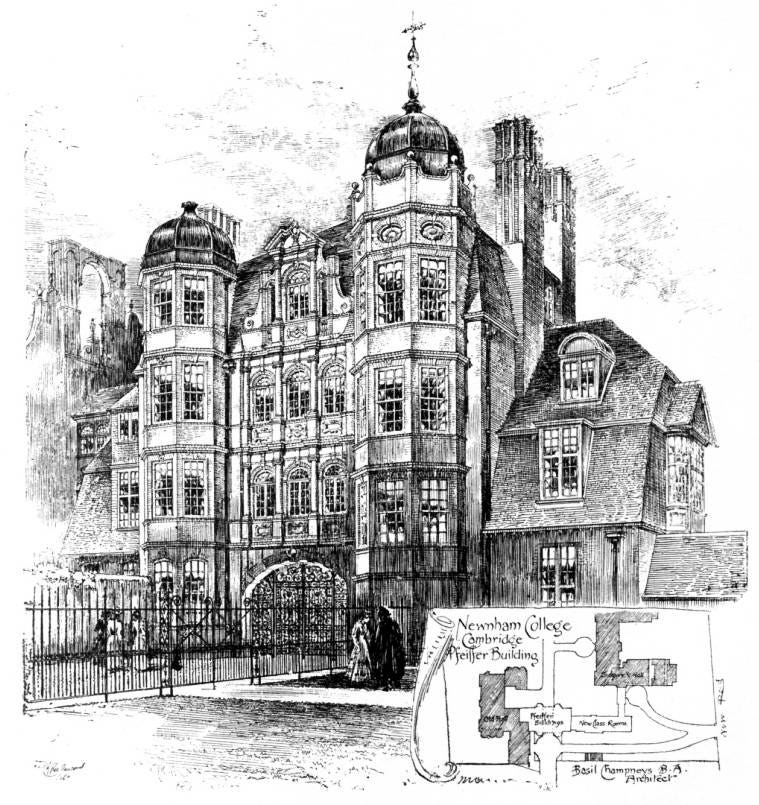

Luckily, there was plenty of work to go around for both firms in the busily expanding Cambridge of the 1880s - and there were no hard feelings, as can be seen by the fact that Leach and Greef worked together on a decorating and bathroom refitting job for Trinity Hall in 1882, as Leach’s work diary reveals.2 Soon afterwards, Louisa Greef’s firm took on a new Newnham College contract. They had been employed there since the mid-1870s as the college’s plumber and glazier, but from Michaelmas term 1885, ‘L. Greef’ had taken over the painting and decorating work previously carried out by F.R. Leach.

Why did Newnham decide to employ Louisa Greef instead of Frederick Leach at this time? It might have been that the Leach firm was too busy, or simply had become too expensive for the college, who had to manage their finances very carefully in the early years. (The Vice-Principal and mathematician Eleanor Sidgwick, in charge of the accounts, called her work ‘chasing twopences’.) As I turned over the pages of Newnham College’s neatly written account books, I thought about the three women in charge during those early years. Eleanor Sidgwick, Anne Clough and Helen Gladstone all worked so hard to ensure their college’s legacy and financial survival, so that other young women would continue to have the opportunity to study at Cambridge. It is possible that they also wanted to support a decorating company run by an honest and reliable professional woman, namely Louisa Greef.

Postscript

The Greef company was financially secure when, in 1891, Louisa handed over the management to her nephew Henry, and she continued to live at King's Parade while Henry managed the business. He later changed his surname to Greef,3 so the family name continued; and Louisa had a long and, it seems, happy retirement, living with her two unmarried nieces, Annie and Alice Fuller. She died in 1913.

While looking through the Greef account books in the university archives I came across something else I wasn't expecting: an estimate book for another woman's painting and decorating business at 3, All Saint's Passage in Cambridge. After her husband's death in 1886 or 1887 Mrs Pratt took over the running of ‘F. Pratt & Son’, the family painting and decorating business. Soon, as she defined herself less as a wife and more of a businesswoman, she was confidently signing estimates and bills under her own name, as 'Mrs Pratt, Painter etc'. She would be the boss for the next ten years, picking up business from domestic customers (university wives and their families) as well as new shops in town, before she handed it over to her son.

With thanks to Anne Thomson (former Newnham College Archivist), author and historian Shelley Lockwood, Mary Naylor (for showing me around Mill Road Cemetery) and the David Parr House team. Any errors are my own. Do get in touch via the Comments section below with any questions or for more information, including about my online talk for David Parr House in April 2022: ‘“A great deal of taste”: Frederick Leach’s domestic commissions in Cambridge, and the women behind them.’ To find out more about Cambridge in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, see Capturing Cambridge.

Further reading:

‘Agnes Garrett (1845-1935)’ in Lizzie Broadbent, Women Who Meant Business: Stories of early business women who broke the mould (online blog article, 2021)

Crawford, Elizabeth, Enterprising Women: The Garretts and their Circle (Francis Boutle, 2002)

‘Suggestions for House Decoration in Painting, Woodwork and Furniture’ by Rhoda and Agnes Garrett (1876)

Garrett, Miranda (2018) Professional Women Interior Decorators in Britain, 1871 – 1899. PhD thesis, University of the Arts London

Greef family account books, Add. 7524-51, Cambridge University Library Department of Manuscripts.

See F.R. Leach diary, 25th March 1882: a reference to a bathroom in Trinity Hall, client's name possibly Maine.

This is lovely stuff - and meat and drink to anyone writing historical fiction. There's always more complexity, individuality and range in real history than the potted versions we're taught.

I hadn't come across Florence Keynes's memoir, except at one remove in reading about her sons Maynard and Geoffrey. Delightful to see Gwen Raverat's illustration on the cover: handy to have an artist as your daughter-in-law's sister!

As one of your commenters said below, Ann, wonderful inspiration for anyone writing historical fiction (something I would love to try my hand at one day). History has always been one of my favourite subjects, but the stuff we're taught at school barely scratches the surface and more often than not completely omits women in the retelling. I can't wait to read more!