Charlotte Mew (1869-1928) was a poet who was ‘very good and interesting and unlike anyone else’, as Virginia Woolf put it. She wrote some of the best English poems of the early twentieth century, and yet her poetry is less well known than her difficult life. ‘Mew wrote many beautiful and devastating poems’ writes Joanna Kavenna. ‘She has her admirers, but remains obscure.’ A fascinating new biography by Julia Copus shifts the focus back to Mew’s poetry, and describes how, despite many difficulties, she carved out a name for herself as a poet who was greatly respected by her peers.

When she was on form, the poet Charlotte Mew was electrifying company, it seems. In March 1914 she was invited to read her poetry aloud to a select gathering of women at Catherine Dawson Scott’s house in London. Although Mew was at first deeply reluctant to do it (‘how I hate it – the performing monkey!’) her friend’s influence in literary circles meant that there might be a chance of some of her poems being published as a result. But because she was the sole breadwinner in her female household (which included her ailing mother, artist younger sister and rambunctious parrot, Wek) she needed the exposure and influential contacts she could get.

So, one stormy afternoon, Charlotte Mew walked from Bloomsbury to Southall carrying her bag stuffed full of handwritten sheafs of paper on which her poems were handwritten. When she got to her friend’s house, she took out her papers, laid out a few of her freshly rolled cigarettes on the table in front of her, and began to read.

Afterwards, the three women who comprised her small audience in Mrs Scott’s front parlour were left stunned, speechless, and intoxicated (not just due to the after-effects of cigarette smoke). As Evelyn Underhill wrote to her friend the following day,

‘My dear Mrs. Scott, I feel as if I departed yesterday without thanking you, but really an hour with Miss Mew is like having whiskey with one's tea – my feet were clean off the floor! Heavens, what a tempest she produced - the most truly creative person I have ever come near.’

It's a delightfully vivid image of this diminutive figure whipping up a storm with the power of her words.

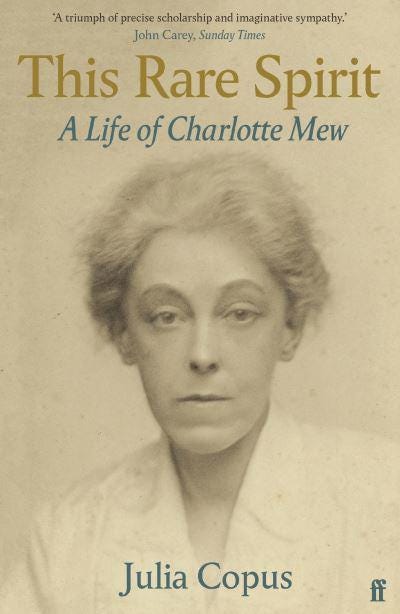

This Rare Spirit: A Life of Charlotte Mew, is a beautifully written and lucid biography by Julia Copus, herself a prize-winning poet and children’s writer. In Penelope Fitzgerald’s Charlotte Mew and Her Friends (1984), Mew is portrayed as an unhappy spinster whose life was scarred by tragedy, shame and unfulfilled lesbian longings.

Julia Copus’s book shifts the focus back to Mew’s distinctive poetry and what she achieved despite all the odds stacked against her. It’s a gripping, beautifully written biography that questions everything we might think we know about this remarkable poet.

The difficulties of Mew’s personal life were legion: an architect father who died young, a brother and a sister who were committed to mental asylums, the family’s shame and persistent financial strains, the prevarications of her publishers and even the demands of her parrot. These are sympathetically portrayed by Copus but the overall effect is that her life was not about tragedy any more than Virginia Woolf’s was, despite her struggle with mental illness. Mew’s determination to be independent, write in her own way and make a living from her poetry is all the more more impressive given her circumstances.

Mew gained her first real attention with the publication of a poem, "The Farmer's Bride," in the Nation in 1912. ‘Having previously only published seven pieces of poetry in various journals, this work established her literary reputation’, as The Poetry Foundation website writes.

The narrative poem tells the story of a farmer and his young wife. The farmer is determined to win the love and affection of his hesitant bride, but instead, they become even more isolated from each other. The poem ends with none of the farmer's desires fulfilled, and he is left lonely, yearning for his wife.’

Charlotte Mew was deeply proud of her work. Convinced that her poems were powerful enough to speak for itself, she kept herself apart from literary cliques (including Woolf’s Bloomsbury set) and avoided most social gatherings.

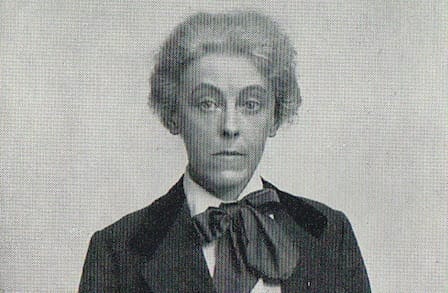

She was a small, short-haired woman who wore tailored men's suits and always carried a black umbrella. But rather than being a hermit, in her letters she is revealed as a spiky and determined with a select circle of loyal friends.

As Julia Copus writes, Mew ‘loved nothing better than to make people laugh, valued loyalty and stood loyally by her friends, spoke her mind, had an aversion to authoritarianism and peppered her letters with cartoonish drawings.’

One of her closest friends was Sydney Cockerell, Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge from 1908 to 1937. He and his wife Florence helped to ensure that Charlotte Mew was awarded a Civil List Pension in December 1923 in recognition of the merit of her work; many writers signed the letter of support.

Although the Civil List pension helped to ease Charlotte Mew’s financial situation, there some difficulties that were simply too great for her to bear alone. She was badly affected by her sister Anne’s illness from cancer and her death in 1927. In her despair Mew began to suffer from delusions, was admitted into a nursing home and took her own life in 1928.

‘So over seven-acre field and up-along across the down/ We chased her, flying like a hare/ Before our lanterns.’ (The Farmer’s Bride)

As a poet, Charlotte Mew’s literary output was modest, with only a dozen stories and essays and one poetry collection, The Farmer’s Bride (1916) published in her lifetime. Despite this, her friend and admirer Thomas Hardy described her as ‘the greatest poetess’ he knew, and Siegfried Sassoon said she was ‘the only poet who can give me a lump in my throat.’ In more recent times, the Irish poet Eavan Boland has described Mew’s 1916 collection as ‘one of the most remarkable poetry publications of the early twentieth century’.

‘Mew’s poems are much more than a fever chart of a harsh existence. They are also a powerful and dissenting conversation with English poetry. She was a rhetorical maverick, with little loyalty to narrative or lyric. Her tone owes almost nothing to the Victorians. It unfolds through big, willful lines that are always on the verge of a prescient, pre-Modernist fragmentation.’1

A couple of years ago I was lucky enough to hear This Rare Spirit’s author Julia Copus reading some of Mew’s poetry to a small audience in one of the oldest houses in Bloomsbury, near Great Ormond Street Hospital. Listening to ‘The Trees Are Down’ and ‘The Farmer’s Bride’ being read aloud in this Victorian front parlour was thrilling, especially when candles were briefly lit, and an indistinct, ghostly image of Mew’s face shimmered on a red velvet curtain behind the author (see below). As I listened to her poetry come alive in that setting, Charlotte Mew herself seemed to emerge from the shadows as a very modern and distinctive presence.

A weapon, a game, a kiss

This week’s TLS features two newly discovered poems by Virginia Woolf. Perhaps it’s generous to call them poems. Sophie Oliver, the UK academic who found them in a folder of letters to Woolf’s niece, Angelica Garnett (née Bell) describes them as ‘doggerel’. It’s probably fair to say that they are not likely to be included in any poetry anthologies, that doesn’t mean that these scribbled verses are not significant. Oliver argues that the point of such verse for Woolf was ‘to play, poke and charm, and to help with what Angelica thought was one of her aunt’s greatest gifts, creating intimacy with people.’

The fascinating Miss Pym

Last week I wrote about the poet Philip Larkin’s correspondence with his mother Eva. This reminded me of another important relationship in his life, with the English novelist Barbara Pym. Despite their different personalities and writing styles, Larkin was one of Pym’s most devoted fans, admiring what he described as her ‘rueful yet courageous acceptanc…

‘Islands Apart: A Notebook. Oliver Goldsmith, Charlotte Mew, and the definitions of a poet’ by Eavan Boland (Poetry Magazine, 21 May 2008)

Still catching up with previous posts and now intrigued about Charlotte Mew having only known her via the PF biography. My mental picture of her has entirely shifted so I will have to find this biography.

Two things jumped out at me…the house near Gt Ormond St. (our GOS nurse’s home in the 1970s was in just such a building) and also mention of Evelyn Underhill. I rarely hear mention of Evelyn these days but her writing was recommended to me years ago by a very knowledgeable local vicar and I certainly followed it up.

Thank you as usual for more trails to follow!

'...like having whiskey with one's tea'. Wonderful! ✨️