Elizabeth Taylor, novelist in waiting (1)

Part 1 (1932-38): An unmuddled attitude to life

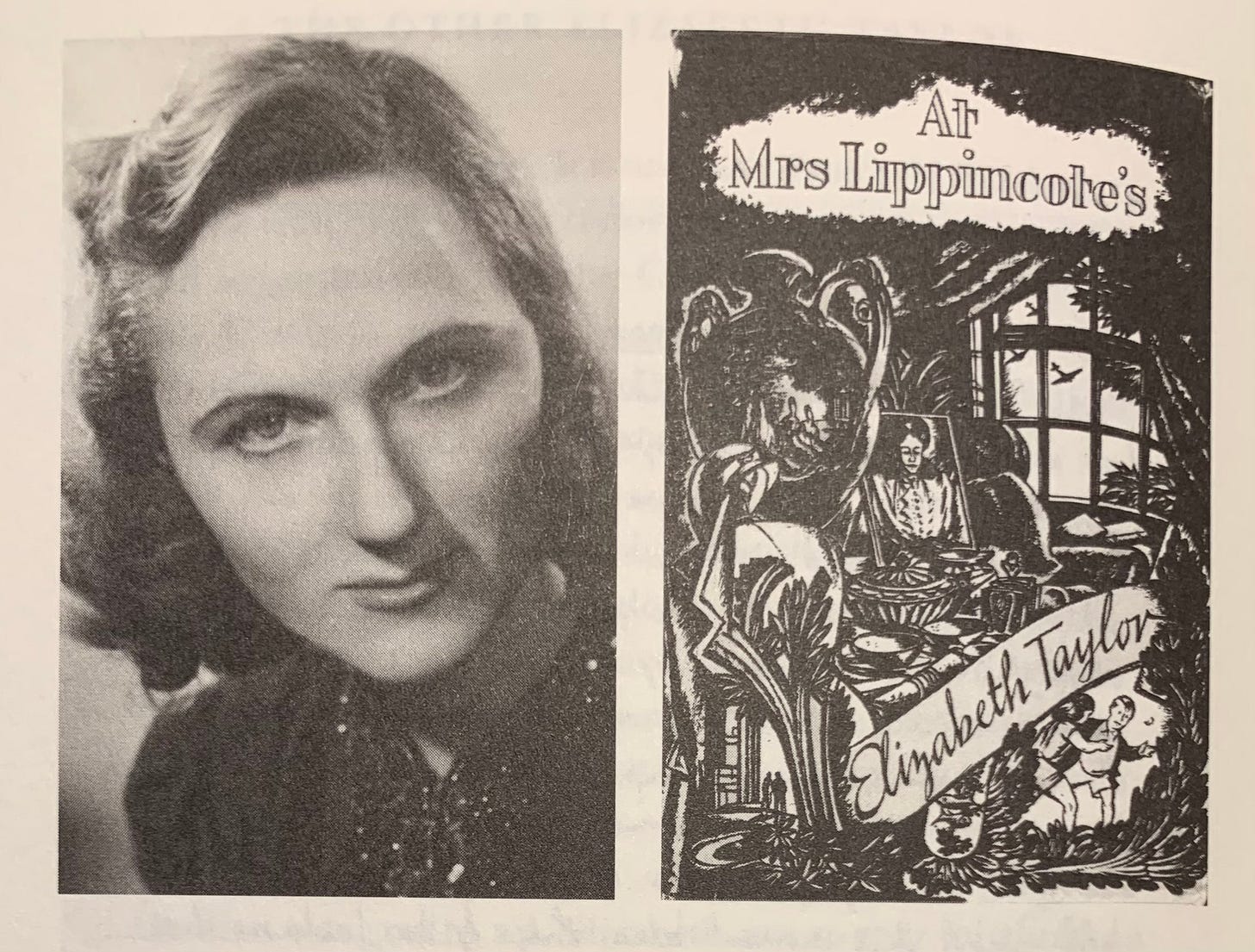

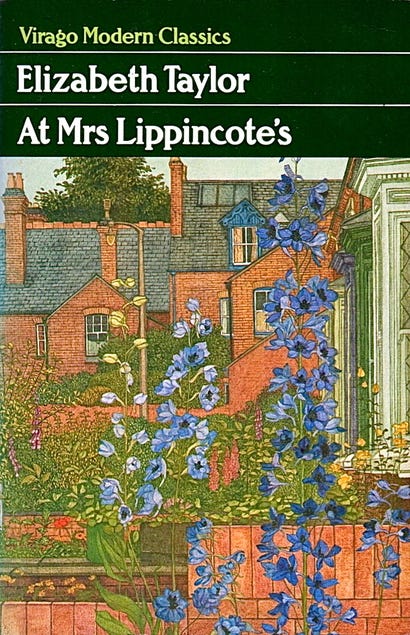

Hello! And welcome to another edition of the Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society. This week’s post is an introduction to the early life of the acclaimed English novelist Elizabeth Taylor, whose novel At Mrs Lippincote’s we’ll start reading this December. As a young woman she showed huge promise and ambition, but there would be great personal sadness in her life too, and it would take over a decade of rejection until her first novel was published in 1945. More details of our At Mrs Lippincote’s reading schedule is at the end of this post. I hope you’ll join us.

Becoming Elizabeth

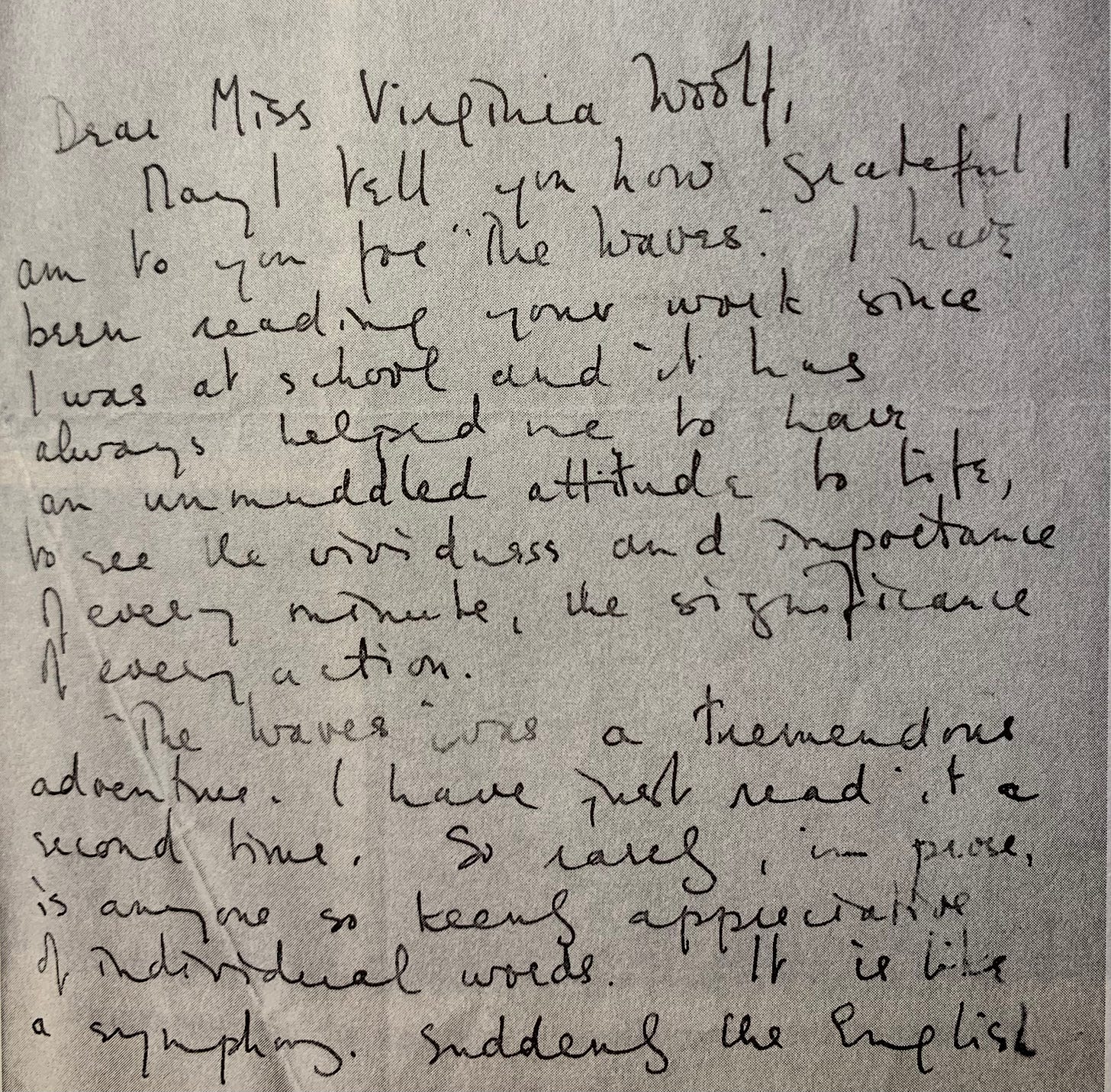

In October 1932 a young woman called Betty wrote a breathless fan letter to one of her favourite authors, Virginia Woolf.

‘Dear Miss Virginia Woolf,

May I tell you how grateful I am to you for “The Waves”. I have been reading your work since I was at school and it has always helped me to have an unmuddled attitude to life, to see the vividness and importance of every minute, the significance of every action.’1

Sadly, Woolf’s reply to this marvellous letter has been lost, but we can assume that it was encouraging for Betty, who later became known as the writer Elizabeth Taylor. Although she struggled to be published for many years, Betty never gave up her own clear-sighted ambition and unmuddled attitude to life.

Elizabeth Coles was born in Reading in Berkshire in 1912, the daughter of Oliver, an insurance inspector who had been invalided out of active service in the First World War, and Elsie, a full-time mother. Elizabeth and her mother were always close. ‘I suppose I lived in the shadow of her loveliness and gaiety and kindness,’ Taylor wrote in 1938. ‘She was not like my mother. She was always my comrade’.2

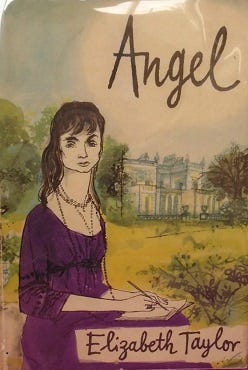

As a schoolgirl at Reading’s famous Abbey School, of which it was said (incorrectly) Jane Austen and her sister Cassandra had once attended,3 Betty read widely. Novels by Austen, the Brontës and Woolf of course, but also Yeats, D.H. Lawrence, Siegfried Sassoon, E.M. Forster and Katherine Mansfield. As well as copying extracts from their writing into her ‘commonplace book’ she started working on her own fiction. After leaving school in 1927 she took secretarial classes in Reading – mainly to please Elsie, who was anxious for her daughter to get a steady job. But at the age of 18, Betty was already confident enough in her future ability as a writer to start sending out her prospective novels to publishers. Elizabeth Taylor captures the disappointment of youthful rejection in her 1957 ‘anti-memoir’ novel Angel. ‘Soon I knew the shame of taking from the doorman a great parcel of rejected manuscripts. “Perhaps my next one will be some good” I wrote in my diary to console myself.’

In 1930 Betty moved with her parents to High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire where she became a part-time tutor and then – after attending an interview ‘dressed to kill, with a hat reminiscent of Gold Cup Day at Ascot’4 – she got the job of head librarian at the local branch of Boots ‘Book Lovers’ Library’. ‘Betty Coles is in charge of Boots Library in High Wycombe,’ announced her school magazine proudly. Book-lover though Betty certainly was, the library job did not represent her long-term ambitions or her desire for adventure. She became an amateur actress and in 1935 met a young man called John Taylor at High Wycombe Theatre Club. He was the son of a local businessman, and would inherit the family business; all this added to his attraction. But Betty was ambitious for herself and wanted to become a famous writer like Virginia Woolf. The last thing she wanted was to marry and end up settling for domesticity in rural Buckinghamshire like her mother Elsie.

Then something happened that changed Betty’s mind. In late December 1935 Elsie Coles suddenly became ill after the family Christmas together, and was admitted to the local hospital with undiagnosed appendicitis. An operation was too late to be successful, and three weeks later she died in January, aged 47, in a side room of the ward. Her daughter later described it with bitter irony as ‘the room of her own, coming to her at the end of a life of drabness and denial.’ Taylor’s bleak summing-up of her mother’s life (from Taylor’s the short story, ‘First Death of Her Life’ ) subvert Virginia Woolf’s lines ‘A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.’

Another side of Mrs Taylor

It was a desperately sad time for 23-year-old Betty, and seven weeks later she left her library job and quietly married John in London. As Mrs Elizabeth Taylor, as she now preferred to be known, she fitted the picture of a conventional new bride: elegantly attired, cooking lunch every day for her husband and spending evenings at home with him in High Wycombe, reading by the fire.

But in other ways the newly married Elizabeth (as she now preferred to be known) was quietly radical. She joined the Communist Party of Great Britain at a time when intellectuals such as Philip Toynbee were joining, and even Virginia Woolf was writing for the Daily Worker. The CP members would often drive together to London to attend political meetings, and Elizabeth, by now pregnant with her first child, met a fiercely working-class young radical called Raymond Russell who worked at a fibreboard mill in the town, and was an aspiring artist (he would later design the cover for the first edition of At Mrs Lippincote’s; Elizabeth disliked it).

Their friendship was forged in their creative connection and a shared passion for the cause. They sold copies of the Daily Worker together in the High Street and had discussions in the party’s cramped headquarters (similar to the flat in ‘Vasco Street’ above the shop in At Mrs Lippincote’s). When her son Renny was a year old, Elizabeth wrote to Ray to confess her feelings for him, and told him what she loved most about him:

‘You did not make the fact of my sex a burden to me, or tiresome. You did not shut me out from any part of your life, or expect me to do less because I was a woman.’5

It was the beginning of a ten-year affair, although for four of those years Ray would be in a prisoner-of-war camp and Elizabeth would give birth to her second child, a daughter. Her marriage to John, and with it a safe domestic respectability in Buckinghamshire, continued. Elizabeth looked elegant, managed her household and her children superbly and wrote whenever she could find the time. It seemed as if the fierce fire that once burned in her to become a novelist had been extinguished.

But beneath the smooth-running domestic surface there was something else going on. During that time, and throughout the war years, she also wrote hundreds of passionate letters to Ray, almost all of which are preserved in an archive today, a remarkable quarter of million words. These are love letters, certainly, but most of all they were a place where Elizabeth gave herself permission to work out important aspects of her creativity. ‘I am in a bad way, so hag ridden with this bloody need to write,’ she told Ray in 1942. ‘Some dreadful strength rushes through me. What is it? Do all human creatures experience this?’… Always I have the feeling that not to write is evil. I shall never get over it now.’6

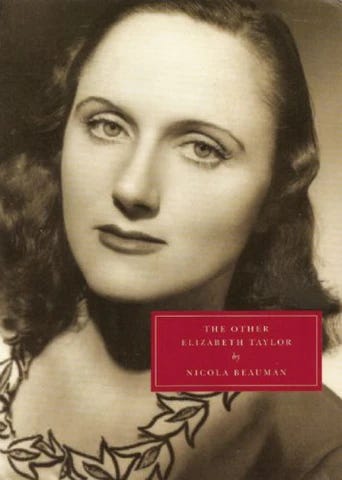

Ray was her comrade, as her mother once had been. He was also her creative brother-in-arms. As Taylor’s biographer writes, the letters ‘reveal the development of a writer’s art over the decade that Elizabeth would call wasted because she was not published.’ But things were about to change, as she started to write seriously again. ‘I begin to smoulder… I Have Started Again.’

Thank you for reading. Next time: Part 2 1942-48.

Reading schedule December 2025-January 2026

Our next book club appointment, all being well, will be on 13/14 December, discussing how Elizabeth Taylor started writing again in 1942, and the opening chapters of her first novel At Mrs Lippincote’s, published in 1945.

We’ll continue our discussion of At Mrs Lippincote’s on 3/4 January 2026, after my festive break 22-31 December. Happy reading meanwhile.

The 20th century book club is a perk for my paying subscribers, who also have full access to the book club archives and my literary essays as well as original posts on Cambridge women’s history. I’m so proud of the friendly community that we’re building here together. Thank you for continuing to support independent research and journalism as we head into 2026!

My posts on other mid-century women writers here:

The fascinating Miss Pym

Last week I wrote about the poet Philip Larkin’s correspondence with his mother Eva. This reminded me of another important relationship in his life, with the English novelist Barbara Pym. Despite their different personalities and writing styles, Larkin was one of Pym’s most devoted fans, admiring what he described as her ‘rueful yet courageous acceptance of things which I think more relevant to life as most of us have to live it’. This post is about how their literary friendship brought about a change in her life that she could never have predicted.

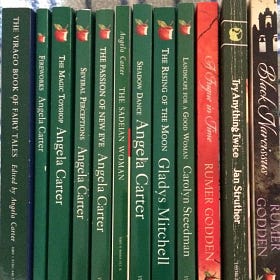

Reading 20th-century women writers

Today’s post is the story of how, back in the 1970s, the UK publisher Virago started re-issuing novels by international women authors from the 19th and 20th centuries. Today there are lots of publishing imprints (eg Daunt Books and Persephone in UK; McNally Editions in USA) as well as magazines and literary podcasts that focus on recovering ‘lost’ literature, including

Other writers on Elizabeth Taylor

‘How deeply I envy any reader coming to her for the first time.’ (Elizabeth Jane Howard).

‘Sophisticated, sensitive and brilliantly amusing, with a kind of stripped, piercing feminine wit.’ (Rosamond Lehmann)

‘One of the best English novelists born in this century.’ (Kingsley Amis)

Further Reading

Nicola Beauman, The Other Elizabeth Taylor (Persephone Books, 2009)

Erica Brown, Comedy and the Feminine Middlebrow Novel: Elizabeth von Arnim and Elizabeth Taylor (Routledge, 2012)

Rachel Cooke, ‘The original Elizabeth Taylor’, Guardian, May 2009

Do read laura thompson, who is simply brilliant on 20th-century women writers. Here she is on Elizabeth Taylor: ‘Elizabeth Bowen was an admirer, as in her caustic way was Ivy Compton-Burnett, and so too (more on this later) was Elizabeth Jane Howard. Nevertheless [Taylor] was far too widely regarded as a ‘writer for women’, a description designed to imply limitations.’ (‘Summer with the Elizabeths’)

For more on Lady Florence Boot, who instigated Boots lending libraries in the UK in 1898, see Lizzie Broadbent’s illuminating essay here.

Quoted in Nicola Beauman, The Other Elizabeth Taylor (Persephone Books, 2009), p.37.

Letter to Ray Russell, 1938.

I am grateful to my reader Anne (and former Abbey school student) for pointing this mistake out to me.

Joy Grant interview, 1978, quoted in Beauman, p. 53.

Quoted in Beauman, p.81.

Letter 152 to Ray Russell, 6 October 1942.

I stumbled across Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont decades ago in the library and was hooked. It is wonderful, and Angel is spectacular. And the rest of her work certainly doesn't disappoint.

I have to keep reminding myself to not confuse her with the OTHER Elizabeth Taylor...