'Charming and violent and gifted'

Virginia Woolf and her nephew Julian Bell

Hello and welcome to Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society. This essay is about the writer Virginia Woolf’s relationship with sister Vanessa Bell’s oldest son, the poet Julian Bell. In 1929, when Julian was a student at King’s College, Cambridge, Virginia wrote to Vanessa: ‘I daresay he’ll give you a lot of trouble before he’s done… he’s too charming and violent and gifted altogether.’ Woolf was right in that Vanessa’s much-loved firstborn child would cause her great pain, but not in ways anyone could have predicted.

War and pacificism

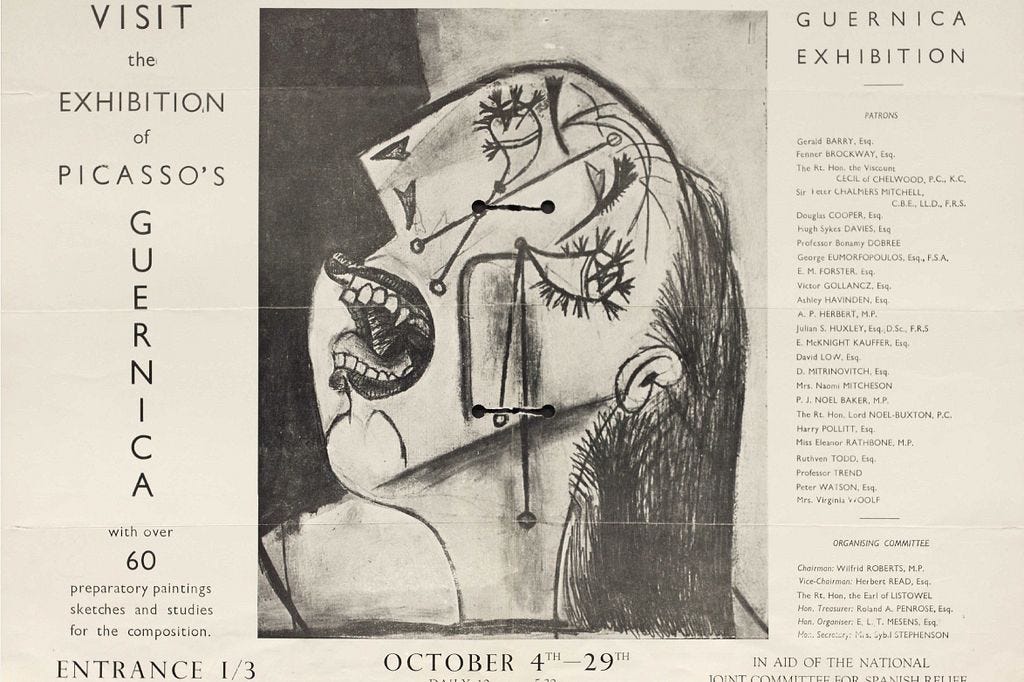

In May 1937 the artist Picasso was in Paris working on what would become his great anti-war painting Guernica, in response to the recent bombing of a town in the Basque country in northern Spain. Vanessa Bell, also an artist, visited him in his studio with her son Quentin Bell, and together they convinced him to donate a drawing to help raise funds for refugee Basque children.

A few weeks later, Picasso’s sketch of a weeping woman was auctioned with other items at the Royal Albert Hall in London on 16 June 1937. But Quentin’s older brother Julian Bell was not present. He had chosen another way to help the cause, and was already on his way to Spain to join the International Volunteers fighting Franco’s forces. He left England on 13th June 1937, planning to work as an ambulance driver and stretcher-bearer. It would be ‘a better life than most I’ve lived,’ he wrote to Vanessa.

A month later he was filling in shell-holes in the road during the Battle of Brunete. When aeroplanes started flying overhead, Julian and his co-worker took shelter under their lorry, but a shell exploded close by, injuring him severely with flying shrapnel. He died on 18th July 1937 at the military hospital at El Escurial, and was buried at Fuencarral Cemetery near Madrid. He was 29 years old.

Vanessa Bell was in her London studio at 8 Fitzroy Street on 20th July when she received the news by telephone that her first-born was dead. She gave a cry so terrible that the wood-carver working in the studio below never forgot it. Virginia Woolf rushed to be by her sister’s side, and did not leave her for ten days. Four years later, following Virginia’s death, Vanessa told Vita Sackville-West how much her sister had helped her during that terrible time.

‘I remember all those days after I heard about Julian lying in an unreal state and hearing her voice going on and on keeping life going as it seemed when otherwise it would have stopped.’

The death of a child

Ten days later Vanessa was well enough to return to her home at Charleston Farmhouse, and Woolf began to jot down her memories of her nephew.

‘I am going to set down very quickly what I remember about Julian, partly because I am too dazed to write what I was writing; & then I am so composed that nothing is real unless I write it.’

Why was it so important for Woolf to write about Julian? As Jane Dunn writes in her double biography of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell, ‘there was a friction always between the sisters over what to Virginia appeared to be Vanessa’s blind maternal prejudice and what to Vanessa appeared to be Virginia’s jealousy and possessiveness. With no one was it more marked than with Julian.’1 Now that her nephew was dead, Woolf could be honest about her own feelings about him.

Her 1937 Memoir of Julian Bell is moving, insightful and honest, and can be read in full here. It’s just a few pages long (5,000 words) and was written, it seems, over a few days. Quentin Bell included excerpts from it in the appendix to his 1972 biography of Virginia Woolf, but the memoir remained unpublished in its entirety until 2005, when it appeared in the academic journal Insights Into The Legacy of Bloomsbury. As the scholar S.P. Rosenbaum writes, ‘the unpublished parts of Virginia Woolf’s memoir display its narrative shape and the extent to which it is a family memoir that reflects her relationships with Vanessa, Julian, and his brother Quentin.’

Rosenbaum notes that while Virginia could write about Julian’s life in her memoir, she was unable to write about his death in her diary, interestingly. The first entry that Woolf wrote in her diary was on 6th August 1937:

‘Its odd that I can hardly bring myself, with all my verbosity—the expression mania which is inborn in me—to say anything about Julian’s death—I mean about that last 10 days in London. But one must get into the current again. That was a complete break; almost a blank; like a blow on the head: a shrivelling up [...] Then I thought the death of a child is childbirth again; sitting there listening. (Diary, V, 10)

Toast or eggs?

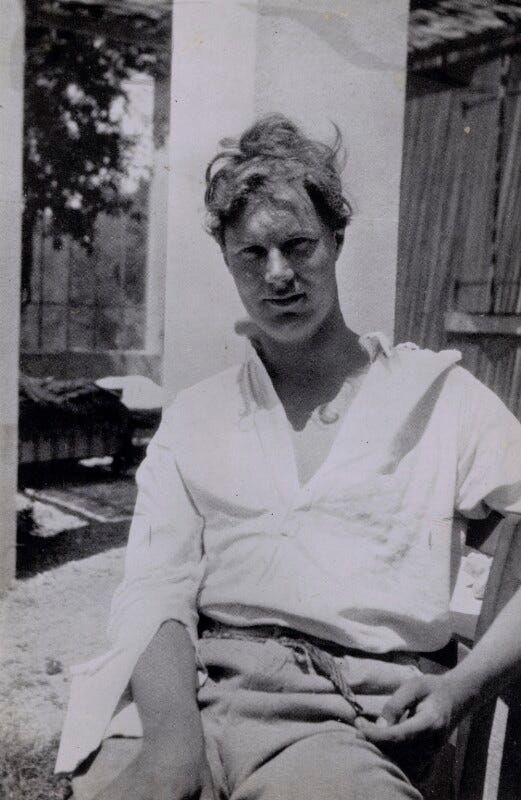

The urgency with which Woolf wrote her memoir of Julian allowed her to bring him back to life in her imagination. She describes the last time she saw him, two days before he left for Spain, and the impact of his physical presence:

‘He had a peculiar way of standing: his gestures were, as they say, characteristic. He made sharp quick movements, very sudden, considering how large & big he was, & oddly graceful. They reminded one of a sharp winged bird—one of the snipe here in the marsh. I remember his intent expression; seriously looking, I suppose at toast or eggs, through his spectacles.’

In Quentin Bell’s biography of Woolf, there is only one entry in the index for ‘moments of merriment’ in his aunt, and even that seen as a warning sign of her imminent breakdown in 1941, while he has a whole section on Woolf’s ‘pathobiography’: all the ways in which her mental health affected her life.

In a Daily Mail article in 1974 entitled “Our Outrageous Parents” Quentin Bell talked about his mixed feeling about being an offshoot of the Bloomsbury set: “As I grew older, surrounded by all those brilliant people, I began to feel – as I told Virginia once – like a toadstool in a forest with all those great trees above me. I felt I was ringed round by enemies.”

Julian and Quentin’s half-sister Angelica Garnett was not very flattering about her aunt either in her own memoir, Deceived by Kindness, seeing her as selfish and taking advantage of her mother Vanessa: ‘there was also a common family habit of referring to Virginia’s ‘madness’ which made it seem quite unreal’ Garnett writes. But she recalls her shock in seeing her aunt near a breakdown.

‘I had been shielded from knowledge of these, partly because Virginia had needed protection when she was suffering from them. But [...] seeing her suddenly threatened left me with the impression of a stoic vanquished only for the moment’.

Although Virginia adored Angelica and loved Quentin, her relationship with Julian seems to have been much warmer and genuinely friendly. Her memoir reveals how often they made each other laugh.

‘And then he laughed— less when he came back,’ Woolf recalled, ‘but he laughed so that he broke chairs. “My dear Aunt—Have you asked him what did you have for breakfast?” one of our stock jokes.’

‘Pictures of Julian at all stages, quite at random, & irrelevant—that is, without throwing light on his development—come to me: one night at Charleston when he suddenly began dancing in the Paddock with Angelica. She was a child then. He danced like a Russian, falling on one knee. It was extraordinarily beautiful; quite spontaneous’

Julian Bell at Cambridge

In her memoir Woolf expresses her lasting admiration for nephew’s ‘clear and strong’ intelligence:

‘he was one of the most directly honest, & sharply & even sternly honest people I have ever known [...] He was very Cambridge. He would wrinkle up his face in a very queer way, the Cambridge way. He would twist his hands. He would make the oddest grimaces.’

Bell’s years at King’s College Cambridge from 1927 were formative in terms of his move towards socialism and his decision to become a poet. When he was his second year in 1928, Virginia Woolf gave two lectures at Newnham and Girton colleges for women, subsequently published as A Room of One’s Own (1929), one of the twentieth century’s most influential reflections on gender politics. She encouraged Julian to think of women students more as intellectual equals, suggesting that he should give his own lecture at Newnham College. Woolf had become aware of what the women students lacked: ‘Why should all the splendour, all the luxury of life, be lavished on the Julians and the Francises…?’ (see my post on Woolf at Cambridge here).

Becoming an Apostle

Julian Bell’s academic prospects and performance while at Cambridge were much discussed by his mother and her friends. The economist John Maynard Keynes kindly wrote to Vanessa in 1929 to reassure her about her son’s promise as a poet.

‘Lytton thinks that the young lack blood and it would be better if they cared more about politics and less about aesthetics; however we all agree that Julian is miles the best of the younger generation.’

A highlight was when Julian was elected to Cambridge’s elite discussion group, the Apostles. ‘I really felt I had reached the pinnacle of Cambridge intellectualism,’ he wrote a few years later. ‘I am still not quite sure how.’ (His Bloomsbury connections, including Keynes, probably helped). At any rate, for Julian becoming an Apostle was the ‘most important event of my Cambridge life’.

In the late 1920s, Anthony Blunt wrote, ‘states of mind were the only thing that mattered’ to the Apostles, ‘and direct action was of quite secondary importance.’

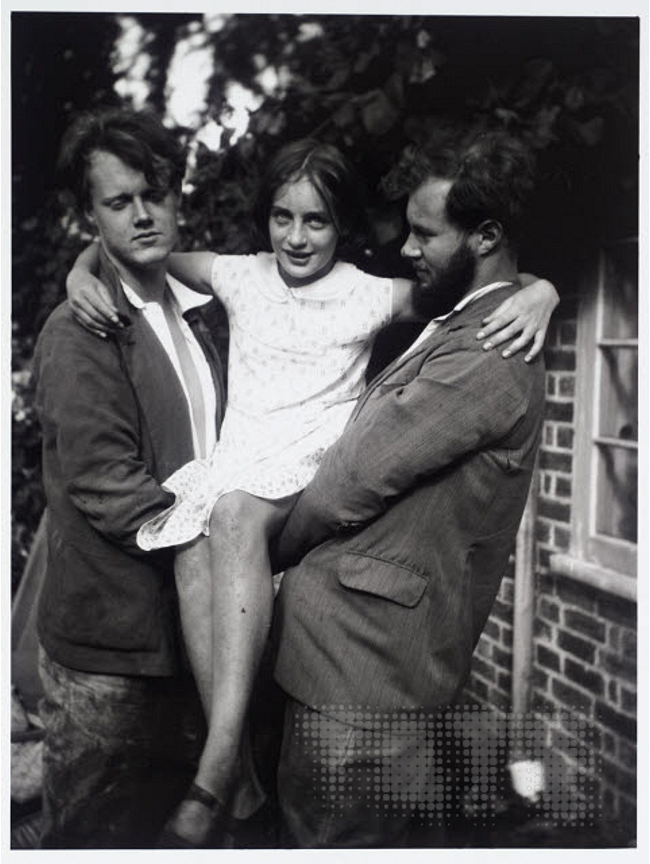

Anthony Blunt (who later would become an art historian and Soviet spy) was a fellow Apostle and Julian’s first lover; after that Bell’s many love affairs were with women.

His relationship with Cambridge photographer Lettice Ramsey meant that she took some of the best photographs of him, and they continued as friends for years after their romantic relationship ended (I wrote about their 1932 trip to Charleston here).

A published poet

While at Cambridge Julian began writing for student magazines, especially The Venture, and publishing his poetry. Near the end of his university career his first book of poems, Winter Movement (1930), ‘was greeted as one of the most promising of its day, and compared to W. H. Auden's Poems (1930)’ (see Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). Virginia and Leonard Woolf did not think a collection of his poems good enough to be published by their Hogarth Press, however, a decision she later regretted.

Following his undergraduate studies, Julian spent four years researching two dissertations, one concerning Pope's poetry and the other on applications of ethics to aesthetics and politics. Neither gained him the Cambridge fellowship he sought, however, and in 1935 he went to China as a Professor of English at the National University of Wuhan. There he became interested in Chinese revolutionary politics. ‘‘I feel it in the same sort of way, with the same sort of strength, that I imagine you must feel about painting’, he told Vanessa. Although he would not want to give her pain, he now believed that some causes were worth fighting for: ‘I have had an extraordinarily happy and complete life, and would rather be killed violently than die any other way.’

He told her of his admiration for Rupert Brooke who ‘wasn’t a poet – much, but the most remarkable human being I’ve ever heard of. I suppose I should have liked to have all his gifts – looks and a fellowship and worldly successes.’ The fact that Brooke died on his way to fight in the First World War was not lost on him, even though Bell had recently edited an anthology of writings called We Did Not Fight: 1914-18 Experiences of War Resisters (1935).

‘The damned literary question’

As well as Brooke’s poetry, one of the modernist literature courses he taught in China was on Virginia Woolf’s novels, which he was delighted about. But what Woolf later described as ‘the damned literary question’ still kept them at arm’s length. She was not impressed by his dissertation on Pope and told him so; she had serious doubts about his talents as a poet; later she felt he should have become a lawyer. In her memoir this is what she most regrets.

‘I was always critical of his writing, partly I suspect from the usual generation jealousy; partly from my own enviousness of anyone who can do in writing what I cant do ... But again that’s my character; & I’m always forced, in spite of jealousy, to be honest in the end. Still this is my one regret; & I shall always have it; seeing how immensely generous he was to me about what I did—touchingly proud sometimes of my writing.’

Woolf’s memoir was her belated apology, a way of paying tribute to Julian and acknowledging his talents. Although she wished she had been more encouraging to him, she felt their relationship was secure, ‘because it was founded on our passion—not too strong a word for either of us—for Nessa.’

‘Julian was bitter at dinner against the Bloomsbury habit of education. He had been taught no job; only a vague literary smattering. But I wanted you to go to the Bar, I said. Yes, but you didn’t insist upon it to my mother, he remarked, rather forcibly. He now finds himself, at 29 without any special training. He is learning the mechanics of lorries. Hadn’t even been taught that at Cambridge.’ Virginia Woolf, Diary, 4 May 1937

In 1937 Woolf was convinced that her nephew should have found some other way of supporting the cause of liberty and she told him so. But when she realized that he was determined to go to Spain to join the fight against fascism she did what only she could do: she encouraged him to write about his experiences.

‘Then, as we walked toward the gate together, I went with Julian, & said, Wont you have time to write something in Spain? Wont you send it us? [...]

And he said, very quickly—he spoke quickly with a suddenness like his movements— ‘Yes, I’ll write something about Spain. And send it you if you like.’

Do, I said, & touched his hand.’

Listening to the past

Woolf’s anti-war polemic Three Guineas was published a year later, in 1938. In her diary Woolf later wrote that writing it had ‘supported her like a spine’ after the horror of Julian’s death and that she was always thinking of him when she wrote it. She told Vanessa that ‘in fact I wrote it as an argument with him’ (Letters, VI, 159).

Yet the feminist arguments and attitudes expressed in Three Guineas are mostly a continuation of A Room of One’s Own, while the third part on ‘arms and the man’ reflects Woolf’s long-held conviction, expressed in her letters, diaries and conversations that it was better to fight for liberty through writing.

Yet there is a sense in which Three Guineas connects the babble of voices and propaganda for and against the coming Second World War, with Picasso’s weeping woman in ‘Guernica’ and the unbearable pain of losing a child.

‘As we listen to the voices we seem to hear an infant crying in the night, the black night that now covers Europe, and with no language but a cry, Ay, ay, ay, ay... But it is not a new cry, it is a very old cry. Let us shut off the wireless and listen to the past.’

This essay is based on my talk for

’s summer programme 2024. Huge thanks to students and other attendees for their stimulating questions and comments. I’m grateful to for her fascinating post which develops themes from my talk: ‘Disciplines, Judgements, and the Questions We’re Compelled to Ask’. My warm thanks also to for her insightful comments on Bell and Woolf; to and others for sending me photographs of Charleston Farmhouse; to Waterstones Cambridge for hosting, and to Literature Cambridge for inviting me to participate in their summer programme. I’ll be giving a talk on the Cambridge scholar Jane Harrison, online and in person, in July 2025; more information and booking details here.You can read more about Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell and their circle in

’s Beyond Bloomsbury and see for more on John Maynard Keynes. (Both highly recommended.) Please let me know your thoughts and comments and thank you for reading.

Sources and further reading

Winter Movement and other poems (Chatto & Windus, 1930) Julian Bell

We Did Not Fight: 1914–18 Experiences of War Resisters (Cobden-Sanderson, 1935) edited by Julian Bell

Work for the Winter (Hogarth Press, 1936) poems by Julian Bell

Julian Bell: Essays, Poems and Letters Quentin Bell (London: Hogarth Press, 1938)

Peter Stansky and William Abrahams, Journey to the Frontier: Julian Bell and John Cornford, their Lives and the 1930s (London: Constable, 1966)

— Julian Bell: From Bloomsbury to the Spanish Civil War (Stanford University Press, 2012)

Jean McNicol, ‘All this Love Business: Vanessa and Julian Bell’ London Review of Books (24 January 2013)

Jane Dunn, Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell: A Very Close Conspiracy (reissued by Virago, July 2024)

Patricia Laurence, Lily Briscoe's Chinese Eyes: Bloomsbury, Modernism, and China (University of South Carolina Press, 2023)

Ros Wong, ‘Bloomsbury in China – Julian Bell, a teacher in Wuhan University in 1935-37’ (online article, October, 2017)

S. P. Rosenbaum, ‘Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell: Memoirs of Julian’ (Insights into the Legacy of Bloomsbury, 2005, republished online autumn 2017)

Frances Spalding, Vanessa Bell (1983) and The Real and the Romantic: English Art Between Two World Wars (2022)

Virginia Woolf, The Diary of Virginia Woolf: Volume 5: 1936-1941 with an introduction by Siri Hustvedt (Granta Books, 2023)

‘The fight to save a Spanish Civil war mass grave’ Guardian article from 2023 about honouring Julian Bell’s and other volunteers’ final resting place.

And if you enjoyed this, below are some of my other posts featuring Virginia Woolf:

Connecting threads (1)

In May 1927, Virginia Woolf gave a lecture at Oxford called ‘Poetry, Fiction and the Future’ and among the audience was a young undergraduate called Gertrude Trevelyan who listened to Woolf’s words about a new type of fiction carefully. A month later Trevelyan became the first woman student to win Oxford University’s most prestigious poetry prize, a huge achievement at a time when the rights of women at Oxford were being contested yet again. The story begins with Virginia Woolf recording her sense of awe after seeing the total eclipse over Yorkshire in 1927.

Coming soon: The Rector’s Daughter Book Club

Last month I mentioned my new feature of my publication: a virtual ‘book-club’. I’ll suggest an overlooked 20th-century novel or memoir and a few weeks later publish a piece about it, followed by an online discussion with subscribers either in a ‘chat thread’ or via the comments section (you can also email me your thoughts: akennedysmith@substack.com). The first book in this series will be The Rector’s Daughter by F.M. Mayor, published 100 years ago this year (see my short introduction here). My essay on this beautiful novel and our first online discussion is planned for 21st September 2024; because of the numbers involved, the discussion will be limited to paid subscribers. Hope you’ll join us!

Jane Dunn, Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell: A Very Close Conspiracy (reissued by Virago, July 2024), p. 279.

Among the many illuminating artifacts you’ve gathered in this moving essay, I’m most struck by the irony of Vanessa Bell securing a sketch from Picasso that would reflect her own grief just a month after the auction. When I look at Guernica (the painting) now, I’ll see Vanessa in the wailing mother of the far left vignette.

As always, you write with both grace & accessibility—a rare combination! I was very touched by the warmth of the bond shared by Virginia & Julian, as I was not aware of their depth of connection. Virginia’s quest for catharsis through the creation of Julian’s tribute seems to have functioned equally as pursuit of a liberating atonement that seemed to elude her tragically in any full sense throughout her haunted life.