Hello and welcome! I had such a lovely time earlier this week, taking part in a discussion hosted by

at the beautiful Libreria bookshop near London’s Brick Lane. Cosi Carnegie’s background is in classics and archaeology, and she’s passionate about sharing ancient history in an informative and accessible way. So I was delighted when she invited me, and to talk about our research and writing as part of a celebration of women in history.We also chatted about writing on Substack and what the future might look like for historical storytelling, as technology and digital platforms evolve. There was wine, laughter and a stimulating exchange of questions and ideas from everyone present. Thank you for all those who were able to join us – it was super to meet fellow Substack writers in person, including

, , , , and others.Do check out this post by

‘Men are great but they're not the whole historical story’ and below there are a couple of questions from Cosi I’ve been mulling over ever since last Thursday. As Women’s History Month draws to a close, which women in history or literature do you think should be known better?In A Room of One’s Own (1929) Virginia Woolf describes looking up ‘position of women’ in G.M. Trevelyan’s History of England (1926). Disappointed to find only references to arranged marriage and Shakespearean heroines, she wondered why there was no room for the lives of real women through history and planned to write her own book following ‘the progress of Anon from the hedge side to the Bankside.’

Women’s history month is all about amplifying voices that have been overlooked. Is there a particular moment or figure from history that you personally think deserves more airtime?

If someone were to leave tonight feeling inspired to explore history or storytelling further, what’s one book, resource, or Substack (other than your own) you’d recommend?

A bouquet of flowers

It’s Mothering Sunday in the UK today. For those of you who celebrate, or who find this day poignant, here’s my post from last year on Charles Darwin’s mother Susannah, who died when he was just eight years old.

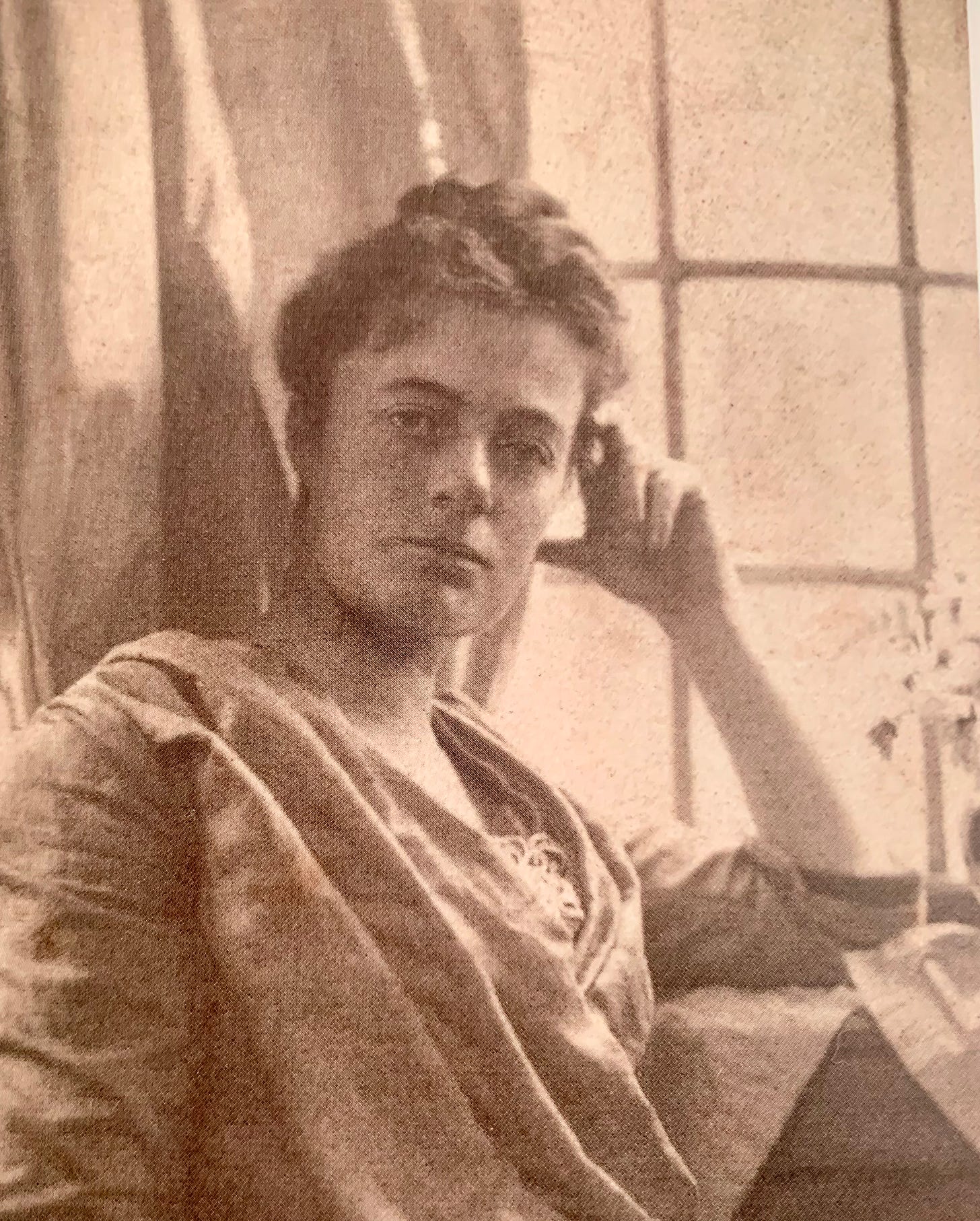

Susannah Wedgwood Darwin (1765-1817)

It’s Mothering Sunday in the UK, the day in early spring in which mothers are celebrated, and traditionally gifts of flowers or plants are given by their children. This week’s post is about Susannah Wedgwood Darwin (1765-1817), the mother of Charles Darwin. Susannah’s influence on her naturalist son is often overlooked, partly because she died when he was only eight. But her vital presence was connected to some of his happiest childhood memories: being at her side in the family’s Shropshire garden, watching her close attention to plants and flowers, learning from her.

Coming up in 2025

I’ll be giving a talk on Virginia Woolf’s friend, the Cambridge scholar Jane Ellen Harrison, as part of Literature Cambridge’s summer school (online and in person) in July; more information about the course here. Below is a link to my essay, based on my talk last year, on Virginia Woolf and her poet nephew Julian Bell.

Next time on Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society

‘At the time of her death in 1978, few of Sylvia Townsend Warner’s books were in print, but her posthumous career has been lively and surprising,’ Claire Harman wrote in the TLS last year, ‘ Coming up next, for subscribers to 20th-century book club, I’ll be writing about Lolly Willowes (1926) and its surprising afterlife. This year’s reading schedule, if you’d like to join us, is here. Thanks very much for reading and subscribing.

*

is the author of the excellent Literature For the People: How The Pioneering Macmillan Brothers Built a Publishing Powerhouse (Pan Macmillan, 2025) and ‘Advocating for the Ignorant’ on Substack.'Charming and violent and gifted'

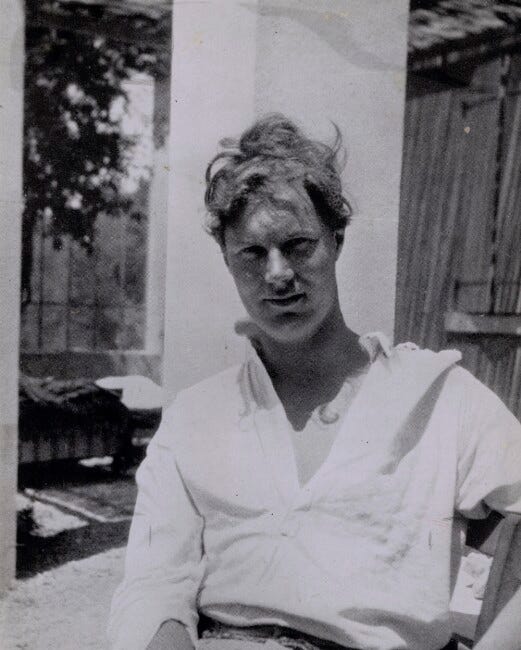

Hello and welcome to Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society. This essay is about the writer Virginia Woolf’s relationship with sister Vanessa Bell’s oldest son, the poet Julian Bell. In 1929, when Julian was a student at King’s College, Cambridge, Virginia wrote to Vanessa: ‘I daresay he’ll give you a lot of trouble before he’s done… he’s too charming and violent and gifted altogether.’ Woolf was right in that Vanessa’s much-loved firstborn child would cause her great pain, but not in ways anyone could have predicted.

How about Elizabeth Montagu (1718-1800) a British socialite, intellectual, and social reformer, who, thoroughly tired of social gatherings where alcohol flowed and men dominated the conversation, got together with a couple of friends to start up a series of more thoughtful and sexually equitable salons, which were hugely popular and - because they valued original thought over formally splendid dress - were affectionately nicknamed the Blue Stocking gatherings. These were both inspiring and influential and certainly were at least indirectly a spur to Mary Wollstonecraft to write A Vindication of The Rights of Women. By the beginning of the 19th century men were getting just a little bit nervous of all this female energy and began actively to destroy the bluestockings by jeering at them and insulting them and gradually the movement wore down. There's very little written or celebrated about them today. But they were the ones who first floated the idea of women's equality, and the debt we modern women owe them is immeasurable.

St. Macrina the younger, a woman theologian in the 300’s AD who taught her brothers, Gregory of Nyssa and Basil, everything they knew. Gregory and Basil were two of the Cappadocian fathers who went on to lay down some of the foundational principals of early Christian theology. Gregory in particular often wrote in praise of his sister. He wrote a biography of her and, in his book On the Soul and Resurrection, which is written as a dialogue, she plays the part of Socrates, answering his questions. Gregory was the first historical figure to explicitly state that the institution of slavery is a moral evil, and he likely did this under Macrina’s influence, as she had convinced her mother to free all their slaves and form one of the first organized women’s monasteries, so she was also a founder of women’s monasticism.