Hello and welcome. I’ve been lucky enough to have been asked to review some excellent nonfiction for the TLS and other literary journals in 2023, and one trend that has emerged strongly is the travel memoir. Perhaps this renaissance of the travel writing genre is due to writers emerging from the cocoon-like restrictions of the worldwide Covid-19 pandemic, or maybe there’s another reason known only to publishers. But armchair traveller and archive explorer that I am, three brilliant travel memoirs by women writers have given me huge pleasure this year, and opened my eyes to different ways of looking at the world. My two previous posts were on what ‘home’ meant to Sylvia Plath and Gwen Raverat. You could say that the recently published memoirs I discuss here reflect on the idea of home being everywhere, and nowhere.

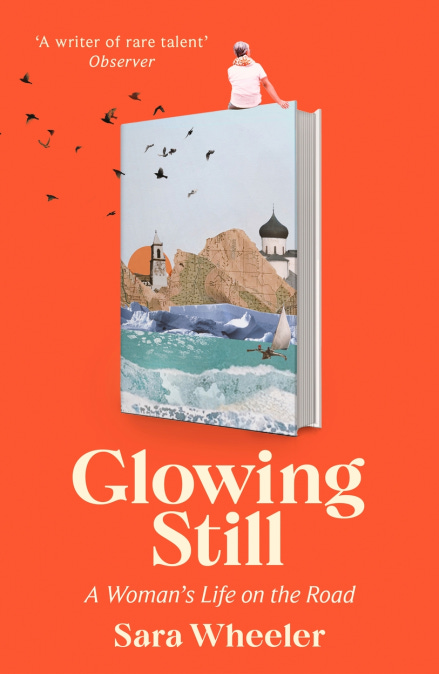

Sara Wheeler’s Glowing Still: A Woman’s Life on the Road was published by Abacus in the UK in March 2023. Wheeler is the acclaimed author of ten previous travel books and two biographies of male explorers, and Glowing Still is a retrospective overview of her almost nonstop travelling across seven continents, from Antarctica to Zanzibar, for over forty years. Her early life was very different; she was brought up in Bristol, by Methodist parents who had blue-collar jobs and deep suspicions of what they called ‘Abroad’. ‘We didn't like anyone who was not like us’, she says of her stolidly conservative relatives. Yet as she grows older and looks back at the freedom she had, travelling solo or with her young children, she gets an insight into her mother’s frustrated longing to see the world. The book’s title is deliberately double-edged: Wheeler smoulders with anger about injustice, inequality and people being displaced from their native lands. She’s also outraged about intrepid women travellers throughout history being excluded from the ‘boys’ club’ of male explorers, and made to feel that their rightful place is in the home. But Glowing Still is primarily a warm celebration of a lifetime of travelling and connecting with people worldwide, and Wheeler is funny and self-deprecating about what travelling so widely has taught her. No matter where you go, she admits, she can never escape from her own limitations. 'I go to the very ends of the earth,' as Isabel Savory writes in A Sportswoman in India (1900), 'and behold, my skeleton steps out of its cup-board and confronts me there.'

Suzanne Heywood’s Wavewalker: Breaking Free is a memoir that takes a very different approach. Suzanne was just seven years old, her brother four, when her parents set off with them on a round-the-world sailing trip in a 70-foot schooner called “Wavewalker” in 1976. It was to be a once-in-a-lifetime adventure, following the route taken by Captain Cook, and it was planned to take no more than two years. Their father, a keen amateur sailor, told their mother not to worry about their children missing out on their schooling. ‘I can’t think of a better education than sailing around the world’, he told her. But after two years there was no sign of the end of the great adventure in sight. Although Suzanne longed to go back home, her parents decided that they would not return to England, and instead make a living by offering sailing expeditions around Hawaii, Samoa and Vanuatu. The children’s wishes for the stability of school and lasting friendships were easily dismissed. “This isn’t a democracy,” their father told them. “The captain always gets the casting vote.” As time went on, any pretence of lessons on board was abandoned, and gender roles were increasingly enforced. While her brother lent a hand on deck and learned to sail, Suzanne was expected to assist her mother in the galley kitchen, cooking and cleaning for their paying guests. She would have preferred to be climbing the masts like her brother: “down below helping do all the housework was not where I wanted to be.” But most of all, she longed for the chance to study and pursue her dream of going to university. She describes her childhood as ‘trapped in someone else’s dream’ and Wavewalker relates how she fought to get the education she needed. Her will as a teenager to gain control over her life is matched only by her courage in confronting her past in this book.

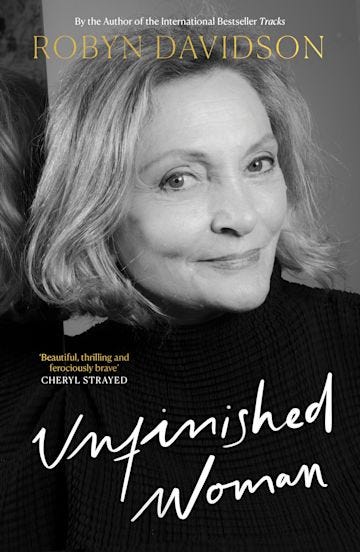

In 1977, when she was twenty-six, a young woman called Robyn Davidson crossed 1,700 miles of Australian desert on foot, with only her dog for company and four capricious camels to carry her gear. Her six-month expedition was originally meant to be ‘a deeply private act’ but the book she wrote about her journey, Tracks (1980), became a best-seller around the world and later a Hollywood movie. Since then, Davidson has travelled and published widely, but her new book Unfinished Woman: A Memoir is about a journey she has never previously written about, her own life. The strength of Unfinished Woman is connected to Robyn Davidson’s honesty about the impossibility of writing about her mother, and the absolute necessity of writing about her as a way of understanding her own past and present. She contrasts the freedoms she has enjoyed - travelling, writing, and relationships - with the constraints imposed on her mother Gwen, a gifted pianist, who, like Sylvia Plath, had to conform to what was expected of a married woman in the late 1950s and early 1960s. She describes growing up in sun-drenched rural Queensland and the family tragedy that at the age of eleven marked the end of her childhood. ‘My mother died when she was forty-six,” Davidson writes. ‘It never crossed my mind to write about her, indeed even to think about her, until I approached the same age. Then that erased, safely buried woman came back with, literally, a vengeance.’ It’s a powerful and beautifully written book, with Davidson dipping in and out of different periods of her past and describing her travels to London, New York and India, exploring forests and deserts, and living in homes that included a squat in Sydney, a fashionable flat in literary London and an Indian palace in the Himalayas. ‘Being a stranger is partly exile and partly the attempt to be at home everywhere,’ as she puts it. Unfinished Woman is about making her way home at last, and finding an understanding of her own life through that of her mother.

Well written reviews. Made me want to ready them.

Loved this, thank you! Very happy we seem to be seeing a travel boom. I've been meaning to read Sara Wheeler for ages!