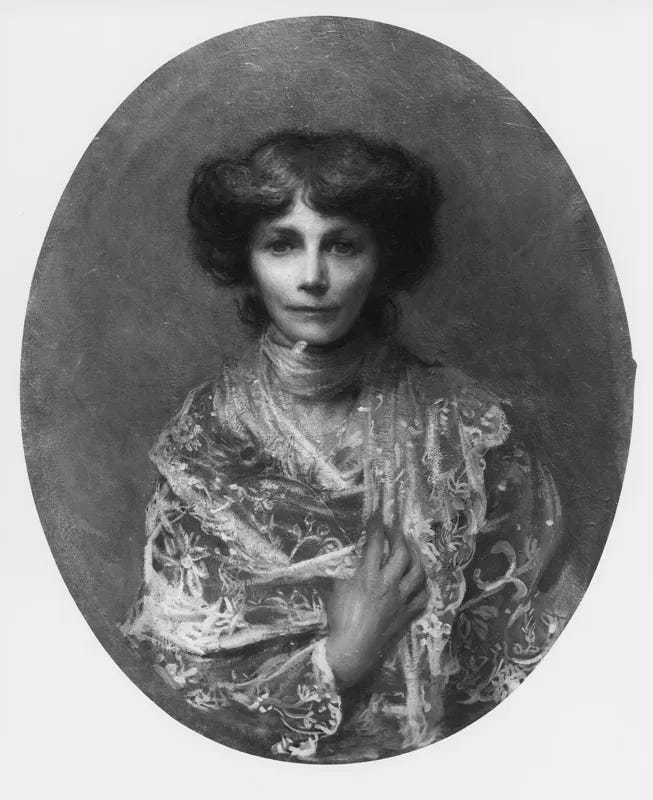

Hello! and welcome to this week’s Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society newsletter. This week’s post is a brief introduction to one of the twelve members of the group, Fanny Prothero. An Irishwoman who moved to Cambridge to be close to her academic brothers, she was bright, funny and insightful and shared the editing of a prestigious journal with her historian husband. But it was her remarkable gift for friendship that I want to highlight here.

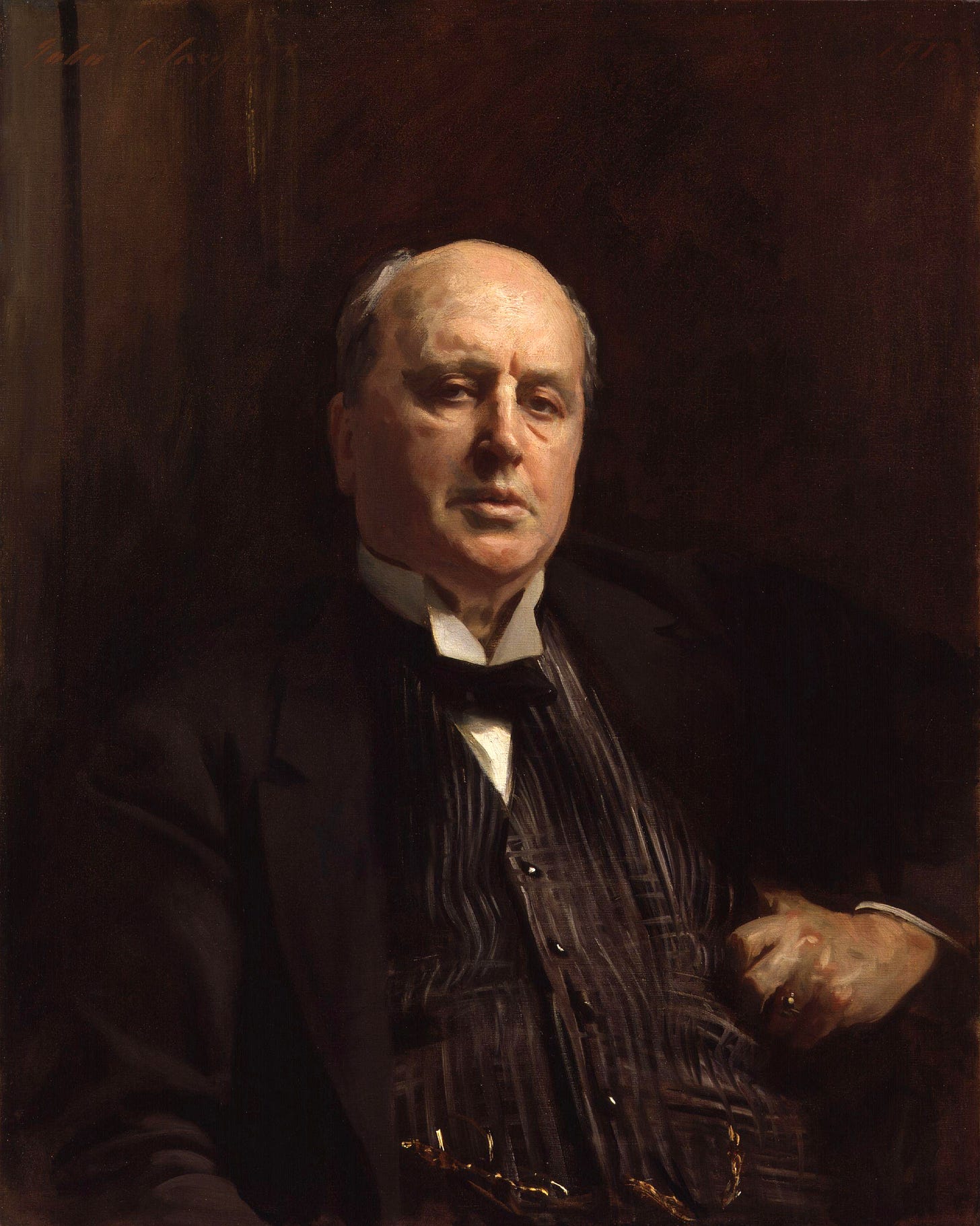

In 1906 the Cambridge historian and editor of the Quarterly Review, George Prothero, 58, and his 52-year-old wife Fanny Prothero took a weekend cottage in Rye in Sussex, close to where Henry James (63) lived in Lamb House. Both of the Protheros soon became part of James’s innermost circle of friends, but it was with Fanny that the great writer could talk most openly, and have the most entertaining conversations.

‘James did like a yarn’, as the Irish writer John Banville writes.

‘He was fortunate in having a large number of female friends who were lively, clever and inquisitive observers of the comédie humaine. It was mainly from these sharp-eyed and sharp-eared women, and most often at the dinner table, that he had many of the instances and ideas for stories that he recorded in his notebooks.’1

Fanny Prothero provided excellent company and good stories. Over the next ten years James would write over a hundred letters to her, warmly addressing her as ‘Dearest Fanny’ or ‘Best of Friends!’ In 1912 he looked forward to inviting her to his new flat in Chelsea for tea ‘and perhaps another opium pill at (say) 4.30. Then there will be such tales to tell!’2

Fanny was born Mary Francis Butcher in 1854, and grew up with her three sisters and two brothers in County Meath in Ireland, where her father was the Church of Ireland bishop, Samuel Butcher. Both of her brothers attended Trinity College, Cambridge and Fanny was a frequent visitor, settling there permanently in 1882 after her marriage to George Prothero, then a Fellow of King’s College, Cambridge. She became good friends with Ida Darwin and her husband Horace, often visiting him during one of his frequent illnesses. ‘I honour a few ladies by allowing them to come and see me,’ Horace told his sister Henrietta Litchfield, ‘the sprightly and vivacious Mrs Prothero and the gentle, charming and refined Mrs Sidgwick.’3

In 1890 both Ida and Fanny were invited to join the select dining and discussion club, the Ladies’ Dining Society. The group had strict rules about sticking to the set topic of the evening; champagne and personal conversations were forbidden, as was personal conversation. ‘Fanny Prothero never really liked it,’ Louise Creighton recalled, ‘she at that time always wanted intimate talk with one person.’

Talking intimately was something that Fanny did best, with both men and women of all social classes. She was useful to Henry James in all sorts of practical ways – helping him to sort out furnishings for his London flat, finding him a reliable cook and frequently popping into the kitchen at Lamb House to sit with her feet on a chair, chatting to his servants. ‘It was her way of keeping an eye on them,’ James’s biographer Leon Edel writes.

But I like to think that it was more than that. Fanny Prothero was genuinely interested in other people, whatever their station in life, and she was as good at asking questions as she was at talking. It was not shyness that made her, in the early meetings of the Ladies’ Dining Society group, lacking in ease at dinner but rather the semi-formality of the occasion.

She was, according to Henry James, ‘the minutest scrap of a little delicate black Celt that ever was – full of humour & humanity & curiosity & interrogation – too much interrogation’.4 In 1913 he confessed to his sister-in-law Alice James (widow of his brother William) that sometimes Fanny’s vivid interest in what he was saying irritated him.

She has a tiresome little Irish habit (it gives at last on one’s nerves) of putting all her responses (equally), at first, in the form of interrogative surprise, so that one at first thinks one must repeat and insist on what one has said… It is her only vice!

When the First World War broke out in August 1914, both Henry James and Fanny (by now Lady Prothero) volunteered for charitable work finding homes for a wave of Belgian refugees and visiting wounded soldiers in hospital. In July 1915, partly in protest at America’s refusal to enter the war, he applied for naturalization in Britain, sponsored by George Prothero among others. James was passionate in his support of the war effort, but increasingly struck down by bouts of poor health, and Fanny Prothero became his devoted nurse in Chelsea. She was ‘as wonderful as ever in her indefatigability,’ a grateful Henry James wrote to his niece Peggy on the evening of 1st December 1915.

It was the last letter that he would ever write. The next morning, as he was dressing, his left leg gave way beneath him and he fell to the floor. His doctor diagnosed a minor stroke and advised bed rest, but it seems that he had a premonition that his death was imminent. Later that day, Fanny came as usual to see him and he told her that as he fell, he heard a voice distinctly say, ‘So here it is at last, the distinguished thing!’

Henry James knew that his friend would want to hear all about it: it was quite a tale to tell. And Fanny Prothero did, later recounting James’s account of his near-death experience to another close friend, Edith Wharton (see this fascinating essay by

on Wharton’s wartime work: ‘Edith Wharton in Paris’.)‘He survived the stroke,’ his biographer Leon Edel writes,

he survived the pneumonia; he lived for more than two months. His mind wandered on faraway places and things; he sat watching the boats on the river through his big Chelsea windows. George V gave him the Order of Merit on New Year's Day, 1916 (for James had become a British subject six months before). He survived until February 28. The funeral was in Chelsea Old Church, and Mrs. William James brought his ashes to America.

Edel believed that it was Howard Sturgis who was told about ‘the distinguished thing’, but we know that Fanny Prothero was one of James’s most dedicated nurses, as well as his confidante, and is the more likely source. Twenty-two years later, Edith Wharton remembered the story and included it in her memoir A Backward Glance (1934): ‘The phrase is too beautifully characteristic not to be recorded,’ she wrote. ‘He saw the distinguished thing coming, faced it, and received it with words worthy of all his dealings with life.’ It was a comfort to Wharton to know that even though she could not be there herself, Fanny Prothero was with Henry James towards the end. They were the best of friends, and she was listening carefully.

Sources: Ann Kennedy Smith, ‘The Ladies’ Dining Society’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (May 2018); ed. Susan E. Gunter, Dear munificent friends: Henry James’s letters to four women, (1999) pp. 192, 228, 193; Leon Edel, Henry James, A Life (1987); Philip Horne, ‘James, Henry (1843–1916)’ ODNB 2004; Edith Wharton, A Backward Glance (1934). For more on Ida Darwin’s historic garden, see my post about Murray Edwards College below.

Writing we loved this week

- asked the question ‘What book(s) did we love this year?’ and I’m enjoying the suggestions from readers (ongoing) while thinking about my own favourites. What books have you enjoyed most this year? I’d love to hear - I’m planning a special end of year round-up soon, with a focus on biography and memoir (delighted that my review of Home is Where We Start by features on the cover of this week’s TLS with James Baldwin).

Where does the phrase ‘women of a certain age’ come from, and is it always an insult? Not so, Professor Deborah Cameron writes in her excellent blog Language: a feminist guide. Historically ‘rather than being disdained as unattractive and undesirable, the “woman of a certain age” is praised for her knowledge, experience and sophistication—qualities which young girls, however beautiful, cannot offer. Honoria Scott’s Amatory Tales (1810), for instance, describes a character as ‘a woman of a certain age, and handsome person; her understanding intelligent and cultivated; she had moved much in the circles of fashionable life.’

On English Republic of Letters there’s a lovely dual post by

and exploring an influential 18th-century Chinese novel, The Dream of the Red Chamber: ‘While I didn’t yet recognize many Chinese characters in the book,’ writes of reading the book as a child, ‘the illustrations drawn in traditional Chinese painting style caught my eyes—those were totally different from any paintings I had seen in my young life, which were mostly depicting workers and peasants and soldiers, as Communist heroes’.‘There can be few other books in American literary history which have had so enormous an impact on the imagination of half the reading population, and have been so neglected by the other half.’ Can you guess what book the influential critic Elaine Showalter is talking about? Yes, it’s Louisa M. Alcott’s Little Women (1868) and in her enjoyable essay

argues persuasively this week that it’s a book (not just a film!) that very much deserves to be taken seriously by modern readers.Good to hear that Caroline Biggs’s book The Spinning House (which I wrote about in Cambridge Notebook 11) has made the national news this week, with Cambridge University being urged to apologize for jailing innocent women without trial in the 18th and 19th century. Thank you

for alerting me to this.Finally, thanks so much for all the wonderful comments on my pictorial post on trees last week. It’s made me appreciate my evening walk home all the more.

Not Afraid of Virginia Woolf

In 1928, a twenty-year-old student called Elsie Phare (later known as E.E. Duncan-Jones) wrote to Virginia Woolf, inviting her to give a talk on the subject of women and fiction to the Arts Society at Newnham College, Cambridge. The society’s president Elsie Phare was in her second year studying English Literature, so it must have been thrilling when one of the great modernist writers of the time provisionally accepted the invitation (the following year T.S. Eliot politely turned her down). The success of Virginia Woolf’s

‘Master copy: Contemporary fruit of Jamesian seeds’, TLS review, May 18, 2018. (https://www.the-tls.co.uk/literature/fiction/master-copy)

Leon Edel Henry James: A Life (1987) pp 643-4.

CUL Darwin family papers, Add. 9368.1.5204.

Gunter, p. 192.

Wonderful essay, Ann, and I’m happy to learn more about Fanny Prothero. The stories of Henry James’ friends could fill many books, I think! Interestingly, Emily Sargent, John Singer Sargent’s sister and best friend, lived down the hall from Henry in Carlyle Mansions i. Chelsea, and was also good friends with Henry, through John, and they often had dinner together. She and younger sister Violet stayed over in Henry’s flat after the second stroke, waiting for Alice James to arrive.

Very interesting. It's not a name I recognise but she sounds lovely!