The curious afterlife of Lolly Willowes (2 of 2)

Reasons to read Sylvia Townsend Warner's 1926 classic today

Hello! I hope you’re having a lovely weekend. We’re currently enjoying very springlike weather in this corner of the UK, and my snap below – of Great St Mary’s in Cambridge earlier this week – shows a madly blossoming miniature cherry tree, despite, or perhaps even because of, its mature age. So it’s very appropriate that this post is about the late-blooming protagonist of Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes. Published almost 100 years in 1926, it’s a short novel that packs in an awful lot that makes it relevant today. So in this post I’m going to explore some of those things, and hope you’ll add your own thoughts. This is part of our 20th-century book club series: thanks so much for joining in, and a very warm welcome to all the new subscribers this month. Here’s our updated April- August reading schedule.

Thanks to

for sending me contemporary reviews from 1926. Do read ’s excellent article, ‘A Life of One’s Own’ (those words, spoken so passionately by Laura Willowes, MUST have inspired Virginia Woolf’s essay A Room of One’s Own published two years later in 1928.) And if you want more proof that Lolly Willowes is having a moment, see ’s Notes below (the latter refers to All Fours, the bestselling novel by – read on to discover more on this novel’s surprising connection to Lolly Willowes).‘It was the only time at which Sylvia could be considered a bestseller, and Lolly Willowes remains the book by which she is imperfectly remembered’ (Claire Harman)

What makes Lolly Willowes live on?

Sylvia Townsend Warner’s first novel made her famous in 1926, and within a year she was earning over eight times her modest income as a musicologist (I wrote about her early career here). Lolly Willowes got rave reviews on both sides of the Atlantic: British reviewers were reminded of the bestselling fantasy novel Lady into Fox (1924) by Sylvia’s friend, David Garnett, while American critics were reminded (curiously) of Jane Austen. When Townsend Warner’s mother told her that ‘it was almost as good as Galsworthy’ and others described it as ‘charming’, Sylvia told Garnett that ‘my heart sank lower and lower.’ Her aims in writing it were entirely different.

But given the first half of the novel, you can see why readers might mistake it for something familiar, akin to F.M. Mayors’s The Rector’s Daughter (1924). Part 1 tells the story of Laura Willowes (she never calls herself Lolly) who grows up with her two older brothers in the Willowes family home, Lady Place on the Welsh borders. Her mother, always ‘invalidish’ takes little interest in her daughter, and dies young; but her father, a gentleman brewer, dotes on Laura. She adores him, and the quiet country life they lead together, and when she comes of age she has no desire to become a ‘young lady’ or to marry any of her prospective suitors.

She did not want to leave her father, nor did she want to leave Lady Place. Her life perfectly contented her. She had no wish for ways other than those she had grown up in. With an easy diligence she played her part as mistress of the house, abetted at every turn by country servants of long tenure, as enamoured of the comfortable amble of day by day as she was. At certain seasons a fresh resinous smell would haunt the house like some rustic spirit. It was Mrs. Bonnet making the traditional beeswax polish that alone could be trusted to give the proper lustre to the elegantly bulging fronts of talboys and cabinets. The grey days of early February were tinged with tropical odours by great-great-aunt Salome’s recipe for marmalade; and on the afternoon of Good Friday, if it were fine, the stuffed foxes and otters were taken out of their glass cases, brushed, and set to sweeten on the lawn. (29)

But everything changes when her father dies. Her brother James inherits Lady Place, and moves in with his wife Sybil and their baby son, Titus who will eventually inherit the property and family business himself. Laura, by now twenty-eight and with five hundred pounds a year of her own, has no option but to leave her beloved home and move to Apsley Terrace in London, where her brother Henry lives with his wife Caroline and their two daughters.

To Laura it seemed as though some familiar murmuring brook had suddenly gone underground. There it flowed, silenced and obscured, until the moment when it should reappear and murmur again between green banks. (64)

When no husband is found for her, Laura is expected to be contented with her life as a useful spinster aunt, who is kept busy for almost twenty years. Even with the disruption of the First World War, and the children growing up and leaving home, nothing changes, or so it seems. With the onset of autumn every year she feels a sense of disquiet, and the risen moon seems to tell her ‘Now! Now!’, but she cannot interpret its meaning.

Then, in the winter of 1921, Laura wanders into a greengrocer’s in Bayswater, where her eye is caught by the ‘bottled fruits, the sliced pears in syrup, the glistening red plums, the greengages.’

She thought of the woman who had filled those jars and fastened on the bladders. Perhaps the greengrocer’s mother lived in the country. A solitary old woman picking fruit in a darkening orchard, rubbing her rough fingertips over the smooth-skinned plums, a lean wiry old woman, standing with upstretched arms among her fruit trees as though she were a tree herself, growing out of the long grass, with arms stretched up like branches. It grew darker and darker; still she worked on, methodically stripping the quivering taut boughs one after the other. As Laura stood waiting she felt a great longing. It weighed upon her like the load of ripened fruit upon a tree. She forgot the shop, the other customers, her own errand. She forgot the winter air outside, the people going by on the wet pavements. She forgot that she was in London, she forgot the whole of her London life. She seemed to be standing alone in a darkening orchard, her feet in the grass, her arms stretched up to the pattern of leaves and fruit, her fingers seeking the rounded ovals of the fruit among the pointed ovals of the leaves. (83-4)

She buys chrysanthemums, which the grocer wraps with a spray of beech leaves which ‘smelt of woods, of dark rustling woods like the wood to whose edge she came so often in the country of her autumn imagination’. Suddenly her course of action lies clear before her.

Just extraordinary writing, isn’t it? If you’ve read Parts 2 and 3, you’ll know what happens next. It really does get better and better: lyrical and satirical, funny and uplifting.

In her introduction to Virago’s 2012 reissue of Lolly Willowes, Sarah Waters emphasizes some of the novel’s political themes and its particular historical context, 1921. Below I’ve suggested a few other issues that make it seem relevant today, as well as the Rural Hours effect, and I’d love to hear your thoughts too.

Class politics

The peace and equanimity that Laura finds in the country, even with little money (her brother invested her inheritance unwisely) is disrupted by the arrival of her charming and patrician nephew. Unlike Laura, for whom class barriers have shifted, Titus is fresh out of Oxford and views the village and its surrounds as his own, entitled playground. What else is the countryside and its quaint rural dwellers for, other than to serve and entertain him as a gentleman? (Even his fiancée-to-be, Pandora Williams plays a rebec, a medieval stringed instrument.)

After a week he knew everybody, and knew them far better than she did. He passed from the bar-parlour of the Lamb and Flag to the rustic woodwork of the rector’s lawn. He subscribed to the bowling-green fund, he joined the cricket club, he engaged himself to give readings at the Institute during the winter evenings. He was invited to become a bell-ringer, and to read the lessons. He burgeoned with projects for Co-operative Blue Beverens, morris-dancing, performing Coriolanus with the Ancient Foresters, getting Henry Wappenshaw to come down and paint a village sign, inviting Pandora Williams and her rebeck for the Barleighs Flower Show. He congratulated Laura upon having discovered so unspoilt an example of the village community. (p.159)

‘Once a wood, always a wood’

An environmental message runs through the novel. This weekend I read some good news (for a change) that England’s non-woodland trees have been mapped for the first time, revealing that suburban and other trees make up nearly third of our nation’s tree cover. It’s part of efforts to boost woodlands, including plans for ‘a new national forest’, apparently. I immediately thought of the wonderful passage towards the end of Lolly Willowes when Satan, in the shape of the loving huntsman, corrects Laura who thinks that the trees have gone forever, telling her: ‘Once a wood, always a wood.’ She turns over his words in her mind, and sees London in a new light. Even in the midst of a city, wild nature is always there. ‘The goods yard at Paddington, for instance—a savage place! as holy and enchanted as ever it had been.’ (231) Some day the woods might take over again.

The Rise of Mid-life Women

The wave of novels about older women who rebel makes us see Lolly Willowes through fresh eyes. In The New Yorker last year, Jessica Winter called it ‘the witty and captivating spinster aunt of the contemporary women’s-midlife-epiphany book’ and finds traces of its influence in the recent fiction of Annie Ernaux and Sally Rooney. What Winter describes as ‘the erotic reawakening of older women’ is found especially in Miranda July’s bestselling All Fours (recently shortlisted in the UK for the Women’s Prize 2025 in fiction). The critic Lara Feigel describes this author as

part of a generation of novelists seeking new forms for midlife – whether it’s “hot-flush noir”, or the plotless, evacuated voice of Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy. The classic menopause novel remains Doris Lessing’s The Summer Before the Dark, another story where a woman abandons her own life and discovers new forms of rage and lust. (Guardian, 16 May 2024)

Righteous Rage

When Titus looks set to make his home in the village, Laura gradually becomes aware that her peaceful, solitary countryside life is threatened, just as it was when she was first forced to leave Lady Place. ‘The wind blew steadily from the old quarter, it was the same east wind that chivied bits of waste paper down Apsley Terrace. And she was the same old Aunt Lolly, so useful and obliging and negligible.’ She feels hunted and helpless, then realizes that, if she wants to keep her independence, she will need to fight for it.

As if by magic, into her room strolls a black kitten which scratches her. She identifies it as her familiar, and that their blood compact gives her special powers as a witch. When she at last meets Satan, who first appears as a benign gamekeeper, then as a gardener, she does most of the talking. By telling him everything, she gains new insights into the lives of ‘useful’ women who are kept busy, but increasingly disregarded as they grow older. Their powers remain hidden until something dramatic happens. ‘Is it true that you can poke the fire with a stick of dynamite in perfect safety?’ she asks.

Anyhow, even if it isn’t true of dynamite, it’s true of women. But they know they are dynamite, and long for the concussion that may justify them. […] Even if other people still find them quite safe and usual, and go on poking with them, they know in their hearts how dangerous, how incalculable, how extraordinary they are. Even if they never do anything with their witchcraft, they know it’s there—ready!” (238)

What makes Lolly Willowes memorable for you, and why do you think it’s still worth reading? How does it compare to other novels you’ve read? You can add your thoughts below, or get in touch with me directly any time by dropping me a line at this email address: akennedysmith@substack.com

Becoming Sylvia

Hello, and a very warm welcome to Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society. Today’s post for paid subscribers features a short introduction to the life of Sylvia Townsend Warner (1893-1978), as a prelude to discussing her novel Lolly Willowes (1926). If you’d like to know more, do have a look at my free post on

More on Sylvia’s revival: The Rural Hours effect

In the 1980s and ‘90s Virago reprinted Townsend Warner’s seven novels over a period of fifteen years, and more recently there have been selected essays and editions of stories reissued by Persephone Press, Black Dog, Faber and Handheld Press. In 2021 Penguin Modern Classics brought out all seven of her novels. ‘This last was the clearest sign yet that Warner is in position to be taken seriously,’ writes her biographer Claire Harman.

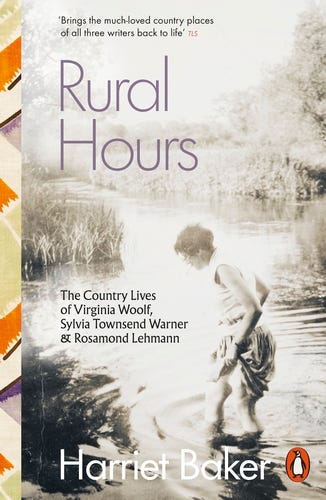

Last year saw renewed interest Townsend Warner’s writing following the release of Rural hours : the country lives of Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Townsend Warner and Rosamond Lehmann by Harriet Baker. As Laura Hackett wrote in her Times review, Rural Hours:

‘is packed with evocative details, such as how Townsend Warner, enamoured with her newly domesticated existence, pitched a cookbook to her publisher called The Devil Sent the Cook (proposed chapters included “Unusual breakfasts” and “Other herbs than parsley”). Baker has just been awarded the Sunday Times ‘Charlotte Aitken Trust Young Writer of the Year Award’, worth £10,000.

Campaigning continues to fund a statue of Sylvia Townsend Warner in Dorchester, with a cat of course (see photo at the top). You can read more about Sylvia’s statue here.

Wise women and witches

Am I imagining things, or has there been a renewal in interest in modern-day witches recently? (Plus tarot readings, and of course, herbal remedies). If you’re in London on 23 April and want to discuss witches, don’t miss this ‘History of the Witch’ evening event at the British Academy, with Dr Laura Kounine, who is co-editing the ‘Cambridge Companion to the Witch’ (Cambridge University Press, forthcoming). I can thoroughly recommend

’s Wise Women: Myths and Stories for Midlife and Beyond (Virago, 2024). Below is a new book from Manchester University Press, featuring a chapter on Townsend Warner’s After the Death of Don Juan (1938). (I do admire a stylish cover design.)In other news…

At this time of year, whenever I see cherry blossom here in Cambridge, I’m reminded of

’s uplifting post, ‘The eternal and ephemeral spring’.And in an unexpected boost this week, I spotted my name briefly at number 26 on the Substack ‘Rising in Literature’ leaderboard of 100 writers. How exciting! This is all thanks to you, my generous paying subscribers, who enable me to keep doing this work. Very much hope you continue to find value in it, and I really appreciate your ongoing support.

Sources

All page references are from the first edition of Lolly Willowes, or The Loving Huntsman, published by Chatto and Windus in 1926 (available to read online).

Eleanor Perenyl, ‘The Good witch of the West’, NYRB July 18 1985; Claire Harman, Sylvia Townsend Warner: A Biography, Penguin paperback, 2015); Dorset County Museum archive; Jessica Winter, ‘The Women’s Midlife-Crisis Novel Enters the Season of the Witch’ The New Yorker, October 19, 2024.

Laughter in the library

Hello and a warm welcome to this week’s edition of the Ladies’ Dining Society. It’s a mild, sunny day as I write here in Cambridge, but the leaves are changing colour rapidly and starting to twirl downwards (always hard to resist gathering those shiny new conkers/horse-chestnuts). Soon students will be returning to their colleges in the town, and some of them might even be lucky enough to study somewhere like this, below. It’s the beautiful Yates Thompson Library at Newnham College Cambridge, designed by Basil Champneys in 1897.

Thank you so much for the mention! And for this great piece - the mention of class is very interesting and something I hadn't picked up on, but of course that sense of entitlement that Titus has is not just because he's male. It's curious that Laura almost seems to shift down slightly class-wise throughout her life, although still not quite enough to put her on a level with the rest of the villagers in Great Mop.

Speaking of the woods, I came across a wonderful new podcast yesterday regarding the National Forest hosted by Dr. Eleanor Barraclough. It’s really interesting.

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-national-forest-podcast/id1806268375?i=1000702019085