The Ladder of Academic Success

By Muriel Bradbrook, English scholar extraordinaire

Hello, and welcome to Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society. This week’s post is about the scholar M.C. Bradbrook (1909-1993), the first woman to become an English Professor at Cambridge University. Her 1951 board game humorously summed up some of the predicaments affecting Cambridge’s academic women even after they had gained equal membership of university (at long last) in 1948. Thanks for reading, and get ready to roll that dice...

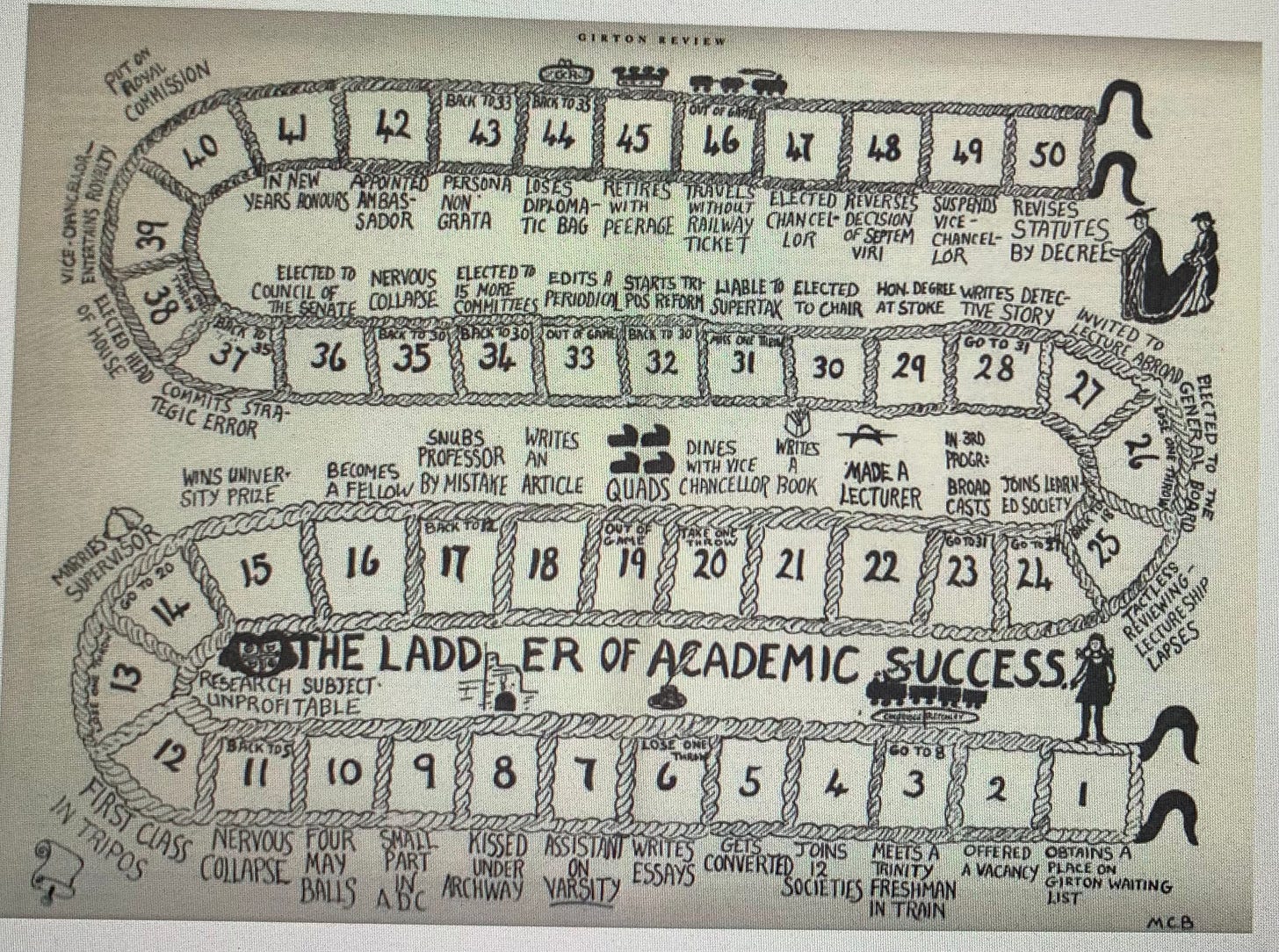

The literary scholar Muriel Clara Bradbrook (1909-1993), better known as M.C. Bradbrook, was the author of seventeen scholarly books on Shakespeare, John Webster and T.S. Eliot among others. She was a fellow and later Mistress (Principal) of Girton College Cambridge, one of the university’s two women’s colleges. In 1951 Bradbrook published a witty design for a board game in the college magazine, which is reproduced in the 2021 Girton College Review. Devising “The Ladder of Academic Success” (which to me looks more like a long and winding road) may have provided her with a welcome distraction from editing the proofs of her Shakespeare and Elizabethan Poetry which was published that year. She had already fulfilled many of the game’s snakes-and-ladders-style moves herself: after gaining a place on Girton’s waiting list in 1927 (square 1) and writing many essays, being kissed under an archway and having a nervous collapse (squares 6-11), Muriel Bradbrook gained the equivalent of a first-class degree in 1930 (square 12) and was appointed lecturer at Cambridge University in 1948 (square 22).

After that, some of her predictions of 1951 came true: in 1965 she was appointed the University’s first woman Professor of English (square 30) then Mistress of Girton in 1968 (square 38, after ‘commits strategic error’ and another nervous collapse) and a Life Fellow of the college in 1976. As far as I’m aware, Bradbrook never published a detective story (square 28) unlike Dorothy L. Sayers, whose Gaudy Night (1935) presents the crime writing novelist Harriet Vane wistfully contemplating an alternative life as an Oxford scholar.

Winning the game (square 50) remained a fantasy in Bradbrook’s lifetime, and so far, ours: it involved a woman being elected as Chancellor, seizing absolute power and abolishing the University’s age-old statutes. It was both an imagined ‘let’s start again, but this time with a woman in charge’ endgame and a tongue-in-cheek riposte to the academic men who were still very much in charge. The ‘septem viri’ (the Latin name for the seven men who ran the University’s disciplinary court), stood for all the Cambridge men who had been writing the rules in the Senate House and excluding women for hundreds of years. But now, at last, the game was up.

A college on Saturn?

When Emily Davies co-founded Girton College in 1869 as the UK’s first residential college for women she was determined that it would become ‘a living branch of Cambridge’. Millicent Fawcett, later famous for her suffrage campaigning, was part of separate scheme run by sympathetic Cambridge dons and their wives and daughters to establish ‘Lectures for Ladies’. At first they had to be cautious not to refer to it as a college: ‘wishing to establish a college for women in Cambridge was like wishing to establish it on Saturn,’ she recalled.1

The first five Newnham College students including Mary Paley Marshall took up tentative residence in a rented townhouse in 1871 under the watchful eye of Anne Jemima Clough. Four years later, Newnham’s first residential building opened its doors to students on its permanent site. It was a tangible, optimistic statement that Cambridge women were planning to stay.

Florence Ada Keynes (née Brown) had happy memories of her time as one of Newnham College’s early cohorts of students (1878 to 1881). In By-ways of Cambridge History (1947) she recalled the prevailing fashion for Pre-Raphaelite art and colourful interior decoration:

‘Newnham caught the fever. We trailed about in clinging robes of peacock blue, terra-cotta red, sage green or orange, feeling very brave and thoroughly enjoying the sensation it caused.’ (p.x)

An unmarried Victorian woman could now live and study in a room of her own in either of these two unofficial colleges, and, with a chaperone, attend university lectures. Funds were raised and scholarships made available to give women an education that was equal to that of her father and brothers. The right to sit for Cambridge University’s final year examinations (the Tripos) was the first hurdle that these early students faced in 1881. The vote giving female students the right to take the Tripos on the same terms as men was passed by the Senate House; as Blanche Clough, later Principal of Newnham observed, ‘there was still a gentlemanly disposition not to refuse to do what you were asked to by ladies’.

Women’s wish for equal access to education could be indulged by Cambridge gentlemen as long as it seemed a light-hearted game, but with proof of their intellectual ability, it became a more serious matter.

In 1887 Girton’s Agnata Ramsay (later Butler) made newspaper headlines by being the only Cambridge student to be placed in the first class of the Classical Tripos, and three years later Newnham’s Philippa Fawcett (Millicent Fawcett’s daughter) outperformed all of the male undergraduates in the Mathematics Tripos. Their striking success in academic subjects traditionally considered to be a male preserve gave a much-needed boost to the women’s cause, but also led to growing unease in some quarters at the prospect of women being awarded degrees. The road to the Senate House was as far away as ever.

In my post ‘No Women at Cambridge!’ I’ve written about the riots that ensued following a vote at the Senate House in 1897 to permit women being awarded the title of B.A. degrees. The antipathy demonstrated towards women students and scholars was deeply shocking to many onlookers.

1948 and after

Given such antipathy in 1897, and another riot in protest against women’s degrees in 1920, it’s perhaps not surprising that Cambridge was the last UK university to give full membership and degrees to women, in 1948. The Queen Mother was the first woman to be awarded an honorary degree in the Senate House, following a grand procession through Cambridge, partly to ensure that there would be no further protests. Muriel Bradbrook composed a (tongue-in-cheek?) ‘Triumphal Ode’ for the royal visitor to celebrate the university’s finally admitting women to full degrees.

At a separate ceremony the female dons were given their degrees, including Bradbrook, belatedly awarded her degree in English Literature. In her inaugural lecture as Professor of English in 1965, she declared of Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens: ‘Life begins on the other side of despair – the maxim of Sartre would not have seemed unfamiliar to the 17th century, for something like it was found in the writings of Luther.’ In 1968 ‘Brad’, as she was fondly known by her students, was elected Mistress of Girton College and oversaw the change in statutes in 1969 when, 100 years after the all-women college was founded by Emily Davies, Girton voted to accept male students and fellows.

‘The dichotomy between “the University” on the one hand and the “women” on the other has passed away’, writes Rita McWilliams-Tullberg, ‘thanks to the patience and persistence of four generations of Cambridge women and their male supporters.’ Patience and persistence indeed. In 1998, 900 jubilant women who had completed their studies before 1948 were invited back to Cambridge to graduate with full honours, and to wear an academic gown for the first time. For them, the road to the Senate House was a long one, and the journey isn’t over yet.

Today, only 40% of lecturers and 20% per cent of professors are female, and there are many other pressing issues around equality, diversity and inclusion at Cambridge University. But women students and academics have played the long game and are gradually winning an equal education at this ancient university. In the main entrance hall of the University Library there is a large painting by Caroline Walker showing two lung stem cell researchers working at the University’s Gurdon Institute. Commissioned for 2019’s The Rising Tide exhibition marking 150 years of women at Cambridge, these scientists seem oblivious to the viewer’s gaze: surrounded by the clutter of a brightly lit laboratory, caught up in their work, these women look as if they have always been there.

Further reading: ‘Obituary: Professor Muriel Bradbrook’ in The Independent, 18 June 1993; Adrian Storey’s delightful short film featuring Muriel Bradbrook’s board game; a richly illustrated overview of 150 years of women at Cambridge, with exhibits from ‘The Rising Tide’ exhibition 2019–20 and a lovely introduction to Mary Paley Marshall; M.C. Bradbrook, "That infidel place": a short history of Girton College, 1869-1969 (Chatto & Windus, London, 1969); a personal post by

: ‘Graduating from Cambridge: The Senate House’.‘I like to live spaciously, but rather plainly, in large halls with great spaces and quiet libraries.’

So wrote the archaeologist and classical scholar Jane Ellen Harrison in her Cambridge memoir, Reminiscences of a Student’s Life, published by Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s Hogarth Press in 1925. Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, published three years later, acknowledges Harrison’s lifelong influence. I’ll be discussing the work of Jane Ellen Harrison in this summer’s Virginia Woolf course for Literature Cambridge. More details here.

Thanks so much for subscribing and supporting the Cambridge Ladies' Dining Society newsletter. I couldn’t do it without you. Coming soon: a post on the author of Lolly Willowes, Sylvia Townsend Warner. Head over to the chat if you’d like to join in the discussion!

Quoted in Rita McWilliams-Tullberg,Women at Cambridge (CUP, 1975), p.56.

My mother read law at Cambridge in the early 50s, she never said that much about it but your article made me realise she was one of the first to gain a degree. Thank you 😘

"The ladies’ wish for an education could be indulged by Cambridge gentlemen as long as it seemed a light-hearted game, but with proof of their intellectual ability, it became a more serious matter." Fascinating perspective, Ann.