Wistaria and sunshine

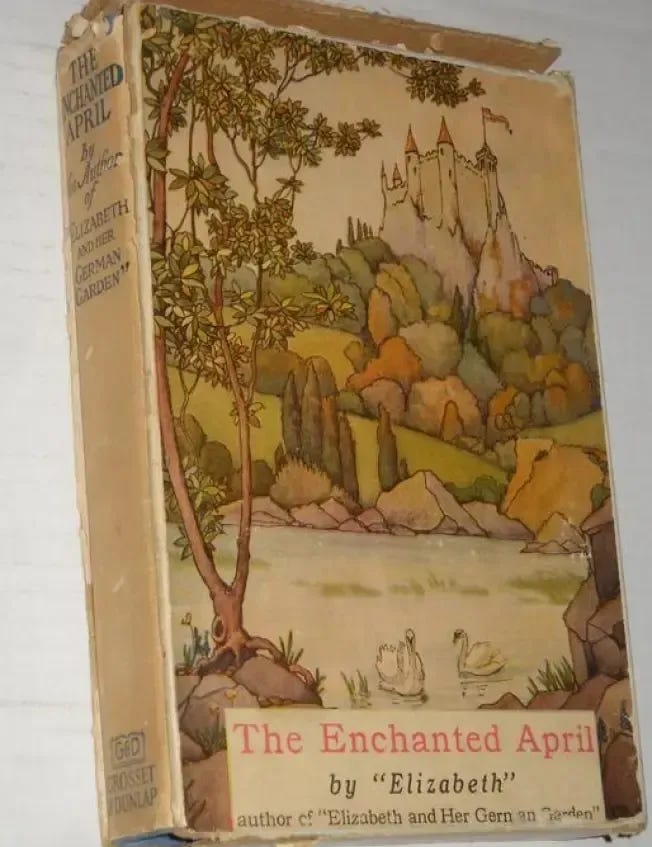

Introducing Elizabeth von Arnim's classic, The Enchanted April (1922)

‘It began in a woman’s club in London on a February afternoon - an uncomfortable club, and a miserable afternoon’: the opening sentence of The Enchanted April by Elizabeth von Arnim sets the scene in a drab postwar London of the early 1920s, when a downtrodden housewife, Mrs Lotty Wilkins from Hampstead, spots an irresistible advertisement in the agony column of The Times:

‘To Those who Appreciate Wistaria and Sunshine. Small mediaeval Italian Castle on the shores of the Mediterranean to be Let Furnished for the Month of April. Necessary servants remain. Z, Box 1000, The Times.’

Beneath the paywall: an introduction to von Arnim’s early life, and how she began to reinvent herself as the bestselling author ‘Elizabeth’. But first, a digression on the long-disputed spelling of ‘wisteria’ in the UK: with thanks to Jo Thompson for sharing this glorious glimpse of English wisteria in full force this month.

Wistaria or wisteria?

A single word in this, surely one of literature’s most famous advertisements, has contributed to one of the longest-running arguments in the respectable pages of The Times. Should the correct spelling for the twining, leguminous, flower-laden plant be wistaria or wisteria? People in England who read this newspaper and live in picturesque houses with names like ‘Wistaria Cottages’ have strong opinions about it, naturally.

Nowadays I tend to agree with the argument that spelling, like the English language itself, is always evolving. It’s simply more usual these days for words to be spelt the way in which they’re pronounced, though I imagine the OED editor Dr Robert Burchfield would have had something to say about that (see my post ‘English as she is murdered’).

I am not alone in this. In 2009 The Times announced, with gravity, ‘We are changing to the phonetically perspicuous but eponymously incorrect wisteria.’ Its style guide of 2016 has a detailed entry on the vexed subject.

‘Wisteria: now prefer to wistaria as the variant for the common name, after epic and absurd controversy in 2009 at The Times. The internationally agreed scientific name for the genus is Wisteria, hence, for example, Chinese wisteria is Wisteria chinensis. The plant was named by Thomas Nuttall, an English botanist, in honour of Caspar Wistar, an American anatomist and physician (1761-1818) and friend of Thomas Jefferson, but bizarrely he decided to spell the genus Wisteria. Wistar’s family came from Germany with the surname Wüster: one branch, so to speak, decided to change it to Wister rather than Wistar, which may have confused Nuttall (for more detail, see a passage and footnote from The Perennial Philadelphians, by Nathaniel Burt). Incidentally, the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia, the first American independent biomedical research facility, also commemorates Caspar Wistar.’1

But the last word has not yet been spoken, it seems, and the wisteria/wistaria argument rumbles on, in the letters pages of this publication at least. ‘Can I entreat your help in rescuing wistaria?’ one reader wrote, pleadingly, later that year. ‘The creeping substitution of an ‘e’ for the first ‘a’ has reached even the columns of The Times. It’s enough to make me hystarical.’

Becoming Elizabeth

Over four decades spanning the 19th and 20th centuries, the author we know as Elizabeth von Arnim produced twenty novels, a children’s book and a memoir called (brilliantly, I think) All the Dogs of My Life (1936). During her lifetime she was known professionally, and later by her friends, as simply ‘Elizabeth’ (the ‘von Arnim’ was added by her publishers), so that is the name I will use here.

Elizabeth was born Mary ‘May’ Annette Beauchamp (usually pronounced ‘Beecham’) in Sydney, Australia in 1866, the sixth child of an English-born businessman, Henry Beauchamp and Elizabeth (née Lassetter) from Tasmania. Her father moved the family to London when she was three, and May became a star student at her girls’ school, a talented musician who spoke four languages.

Always ambitious, she decided that she wanted to study history at one of the new colleges for women attached to Cambridge University. But poor health prevented her from taking the entrance exams, so instead she became one of the first women to study at the Royal College of Music. There she discovered a passion for organ-playing, and decided to become a professional musician.

But her parents had other plans for her. In the hope of finding a suitable husband for their twenty-two-year-old daughter, her father took her on a tour of the Continent, attending concerts and musical evenings. May preferred listening to Wagner and Liszt than to the sweet-talking of hopeful suitors, but she did fall in love; not with a man, but with the romantic ‘English’ gardens of the Villa Durazzo-Pallacini at Pegli, near Rome.

‘Emerging as she had from the gloom of London in January, nothing could have been better designed to make an impression on May at this stage in her life,’ her biographer writes. ‘Ideas associating paradise on earth with Italy and gardens were already being forged.’2

Soon afterwards, at yet another musical evening, Elizabeth and her father were introduced to a Prussian Count, Henning von Arnim, in Rome. He was a widower who was fifteen years older than May and struck by her petite beauty and musical talents. Von Arnim was an impressive figure who used his aristocratic title and charisma to bluff his way through serious financial difficulties. He began to arrange May and her father’s travels around Germany and wooed her rather forcefully it seems. He took her to the top of the Duomo in Florence and told her: ‘All girls like love. It is very agreeable. You will like it too. You shall marry me, and see.’3

Reader, she did marry this less than charming suitor two years later, but that certainly wasn’t the end of her story. Having spent the first part of her married life in Berlin and becoming fluent in German, a visit to her husband’s country estate at Nassenheide in the spring of 1896 convinced her to move the family there permanently. In this beautiful garden, surrounded by her three young daughters, May would write Elizabeth and her German Garden (1898) and almost overnight become the celebrated author ‘Elizabeth’.

We’ll be discussing The Enchanted April (1922) over the next few weeks. Topics include women’s roles in this novel; is it escapist fluff or a feminist fairytale? Why has The Enchanted April been dismissed as a ‘middlebrow’ novel, and what does this tell us about literature by/for women in the 1920s? We’ll investigate the significance of the post-war setting... and much more besides. I do hope you’ll join us. More details about the 2025 book club schedule here:

20th-century book club schedule

Hello & a warm welcome to Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society, especially to all the readers who have joined recently and to my very generous paying subscribers. I greatly appreciate your kind support, and hope you’ll enjoy being part of this friendly community in 2025. This is just a short post, outlining the next three novels lined up for our 20th-century book club from April to July. Read on to find out about some of the other new things coming for this newsletter in spring. All dates are provisional… and I would love to read any comments from you on these novels, or any other books you’ve enjoyed.

English as she is murdered

Hello and welcome to Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society. This week’s edition follows on from my most recent post featuring the subject of English punctuation, with good news for fans of the (almost defunct) diaeresis. Below is my article about Robert Burchfield, a scholar who dedicated his life to dictionaries and the study of the English language. When in 1980 he was asked by the BBC to offer his advice on the thorny issue of ‘good English’, he became an unlikely celebrity, with appearances on TV and radio. He later became a more contentious figure,

A weapon, a game, a kiss

This week’s TLS features two newly discovered poems by Virginia Woolf. Perhaps it’s generous to call them poems. Sophie Oliver, the UK academic who found them in a folder of letters to Woolf’s niece, Angelica Garnett (née Bell) describes them as ‘doggerel’…

I’d love to hear about your own experiences of a life-changing trip when you were younger, or a garden (real or fictional) that has stayed in your memory. If you have strong feelings about wistaria/wisteria, I’d love to hear about that too. Thank you for reading, and do click on the heart if you have enjoyed this post - it helps others to find it.

‘Reader warning: Times tides wait for no man’ The Times, 11 June 2016.

Jennifer Walker, Elizabeth of the German Garden (Book Guild, 2013).

How interesting, and depressingly unsurprising, that this gorgeous novel has been labelled 'middle-brow'... but then the same happened to those other wonderful Elizabeths, Taylor and Jane Howard, so it's in good company... I knew very little about E von Arnim's life so thank you Ann! Fascinating as always.

You have solved a mystery for me - 'named in honour of Caspar Wistar'! I say wisteria as using the scientific name is easier for work purposes, but I love this explanation - thank you.

For me, wisteria and Venice are tangled up with each other. This year, a friend and I spent four days on the hunt of every wisteria we could find in the city, their scent announcing the presence of the plant before you actually stumble upon the plant itself. Like Bisto kids, we'd follow the fragrance which hangs low in alleys and courtyard, pursuing it until we thought we'd come to yet another dead-end. And then, all of a sudden, there it was - dangling above us, tempting us...

I'm so excited about this book - it's one of my favourites.

While we're on the subject (gosh, I could go on for days about this), many people ask me about their non-flowering 'wisterias' which they bought perhaps a decade ago, and yet there's still no sign of a bloom. The trick is that when you're buying it, wait until flowering season and make sure the plant you buy actually is blooming and has a raceme (cluster) of flowers on it. That way you know you're pretty much guaranteed flowers the following year 🌱