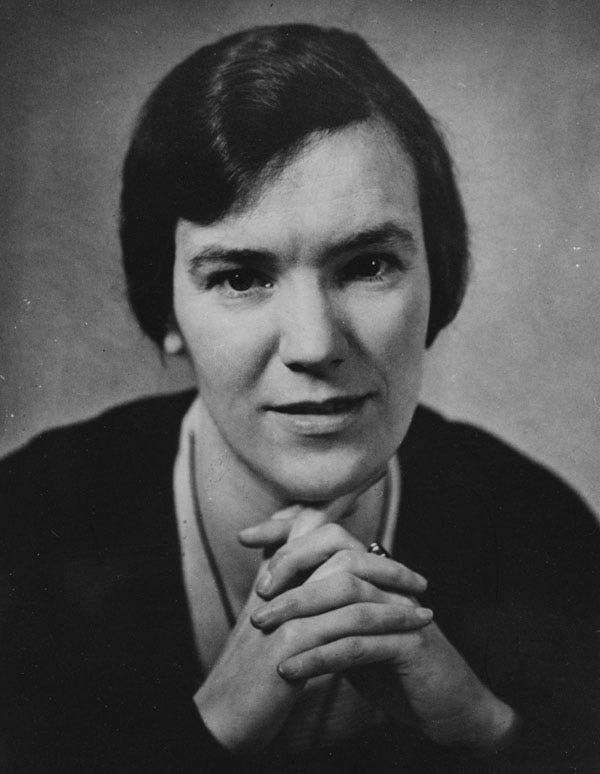

Hello and welcome to Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society. In this post, part of my series about women academics who were educated at Cambridge University, I consider the life and influential work of the British economic historian and medievalist Eileen Power (1889-1940).

In her essay called ‘Women at Cambridge’, published on 14 February 19201, Eileen Power recalled the occasion when, as Director of Studies at Girton College Cambridge, she was asked by a male colleague for a ‘woman's perspective’ on a problem. She argued that:

‘a woman's outlook on art and science has nothing specifically womanly about it, it is the outlook of a PERSON… The difference is between good books and bad books, straight-thinking books and sentimental books, not between male books and female books.’

Eileen Power was born in Cheshire in 1889 and began her studies at Girton College in 1907, funded by a scholarship, where she was taught by the influential historian Dr Ellen McArthur. Following a year in Paris, and a studentship at the London School of Economics (LSE), Power became a fellow in history at Girton in 1913, where her easy charm and stylish appearance made her stand out against the more sombre hues of other scholars. ‘I certainly feel there is something radically wrong with my clothes from an academic point of view’, she told her sister Margery.

Male historians had a habit of underestimating her work based on how she looked, but they soon changed their minds after reading her thoroughly researched books. As Francesca Wade comments in her recent group biography, Square Haunting (Faber/ Penguin Random House paperback, 2021), ‘Power saw no reason why an interest in clothes and a sense of humour could not be combined with professional rigour.’

Eileen Power’s travels

During the First World War Power taught economic history at both Girton and the LSE, but after the war she failed to get the permanent position that she hoped for (her lectureship at Cambridge was given to a man). Her future career as a historian seemed uncertain, but her life changed in a way few could have predicted when in 1920 she was awarded the prestigious ‘Albert Kahn Travelling Fellowship’, which granted £1,000 to scholars for a year's global exploration. Eileen Power was the first woman to win this international honour, and was told by one suspicious interviewer that ‘she might defeat the objects of the trust by subsequently committing matrimony.’

She defied her critics, and those who assumed marriage was every woman's chief ambition, by travelling alone to China, Egypt, and India. As a committed pacifist and Labour Party member she was delighted to meet Mahatma Gandhi, and she was one of only six Europeans to witness the Nagpur Congress assembly vow to adopt Gandhi's policy of Non-cooperation. Eileen Power refused to attend genteel colonial parties or to be daunted by obstacles as she travelled; when she discovered that the Khyber Pass was closed to women, she simply put on male disguise and made the crossing anyway.

Visiting the British colonies in India and spending two months in China, talking to locals and government officials, Power began to grasp the impact that the British Empire had on the people who lived there, and the complicated reality beyond ‘the historical textbook of the debating society’. Her travels gave her curiosity and empathy that informed her later work, seeing history from the point of view of ordinary people, not their rulers.

While in India, Eileen Power received a letter that would change her life again. It was an offer of a lectureship in political science from the London School of Economics (L.S.E.). She hesitated about giving up her hopes of a Cambridge position because, as she told a friend, it ‘would mean a lot more teaching than I've done before & the screw [=salary] is only £500 - but I want to be in London for a bit.’ The lectureship in London was originally intended as a more prestigious Readership, with a salary of £800 for a man, but when they offered it to Power they called it a lectureship and reduced the pay accordingly.

Throughout her life Power was consistently paid less than her male colleagues, even after she became L.S.E.’s Chair in Economic History in 1931. By then she had become a renowned scholar who was regularly invited on international lecture tours and awarded honorary degrees from respected universities. Her books include Medieval English Nunneries (1922), Medieval People (1924) and Medieval Women (reissued in 1975). She also co-wrote children's history books with her sister Rhoda Power, gave public lectures, and presented a World History series for BBC radio in the 1930s.

Mecklenburgh Square gatherings

From 1921 until 1940 Eileen Power lived in Mecklenburgh Square on the unfashionable eastern edge of Bloomsbury, as did her colleague and friend, the economic historian R.H. Tawney. Under his influence, Power's medieval historical research took an overtly political turn. She and Tawney co-edited a book, Tudor Economic Documents, published in three volumes from 1924 to 1927, and they were both founding members of the Economic History Society, an international alliance of scholars. Power edited its influential journal the Economic History Review.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s there were regular gatherings of political leaders, journalists, theorists and writers, including Hugh Gaitskell, Evan Durbin and Hugh Dalton at both Tawney's and Power's rented flats in Mecklenburgh Square, but RH Tawney has a blue plaque there, while Eileen Power does not. Yet during her lifetime she was as famous as he was. In Testament of Friendship (1940) Vera Brittain describes how, when she and Winifred Holtby were preparing to give up their flat in nearby Doughty Street to move to the suburbs in the 1930s, one horrified friend asked them, ‘Why are you leaving the neighbourhood of Tawney and Eileen Power for a place called Maida Vale?’

Cursed with hearts and brains

‘London itself’, wrote Virginia Woolf in 1928, ‘perpetually attracts, stimulates, gives me a play and a story and a poem, without any trouble save that of moving my legs through the streets.’ Francesca Wade’s Square Haunting: Five women, freedom and London between the wars

‘I like people to be all different kinds,’ Eileen Power told a friend in 1938, explaining why she had not applied for a prestigious history professorship back in Cambridge. ‘I like dining with H.G. Wells one night, & a friend from the Foreign Office another, & a publisher a third & a professor a fourth’. Her regular ‘kitchen dances’ in Mecklenburgh Square were attended by economists, politicians and writers: at one party Virginia Woolf recalled sharing a packet of chocolate creams with a civil servant.

A marriage of equals

In Square Haunting Francesca Wade recounts how Power was described (wrongly) as a 'love interest' of R.H. Tawney rather than his co-worker and friend. Power valued her independence, and for most of her life was opposed to marriage as an institution, convinced that it was incompatible with a woman's public ambitions. The ideal wife, Power joked, ‘should endeavour to model herself on a judicious mixture of a cow, a muffler, a shadow, a mirror.’ When in 1937 she finally decided to marry her former student and LSE colleague Michael ‘Munia’ Postan, ten years her junior, it was a carefully considered decision, ‘a satisfactory balance of head and heart’, as Wade writes. Sadly, just three years later Power died suddenly of a heart attack, aged just 51.

Power wanted to inspire through her work a sense of ‘international patriotism’, a sentiment echoed in Woolf's Three Guineas (1938) ‘As a woman, I have no country... as a woman my country is the whole world.’ Power was critical of Britain’s foreign policy in the 1930s and established the Academic Freedom Committee with William Beveridge to aid academics fleeing Nazi Germany. As she wrote:

[There is] no more powerful means of binding nations together than by the infinite multiplication of these tiny invisible threads of personal contact and mutual understanding.

Famous during her lifetime, after her death, much of Eileen Power’s important work was gradually forgotten. In an attempt to keep her memory alive, her sister Beryl Power, a leading civil servant, endowed a dinner in her honour at Girton College because, as she said, ‘men’s colleges had feasts and why should not women’s?’ Today, international scholars and historians gather for the ‘Power Feast’ every ten years; the most recent Feast took place in 2020, almost exactly 100 years after Eileen Power’s ‘Women At Cambridge’ essay was published.

Sources: Francesca Wade, Square Haunting (Faber & Faber, 2020); Maxine Berg, A Woman in History: Eileen Power (1889-1940) (CUP, 1996); 'Eileen Power' LSE website (accessed 18.2.24); 'The Rising Tide: Women At Cambridge', Cambridge University Library exhibition website (accessed 18.2.24); ‘Popular history and the Power sisters’ Royal Historical Society blog (accessed 18.2.24).

“Famous during her lifetime.” And I am being introduced to Eileen Power for the first time. An extraordinary woman, an incredible life. Why aren’t film studios fighting over the rights to her story? I’m thinking Cait Blanchett should portray her.

What a gift, Ann. Thank you for bringing your remarkable talents to another brilliant woman’s life.

What an extraordinary trio of sisters, from very unpromising beginnings. The grandmothers and aunts who brought them up did a fantastic job!