Caroline Jebb's war

'If you men will not defend your country’s flag, I will!’

Hello! Welcome to Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society. This week’s post is about Lady Caroline Lane Reynolds Slemmer Jebb, who became a well known social hostess in Cambridge and London in the 1890s, a friend of writers and politicians and a suffrage campaigner, and a leading member of the Ladies’ Dining Society (1890-1914).

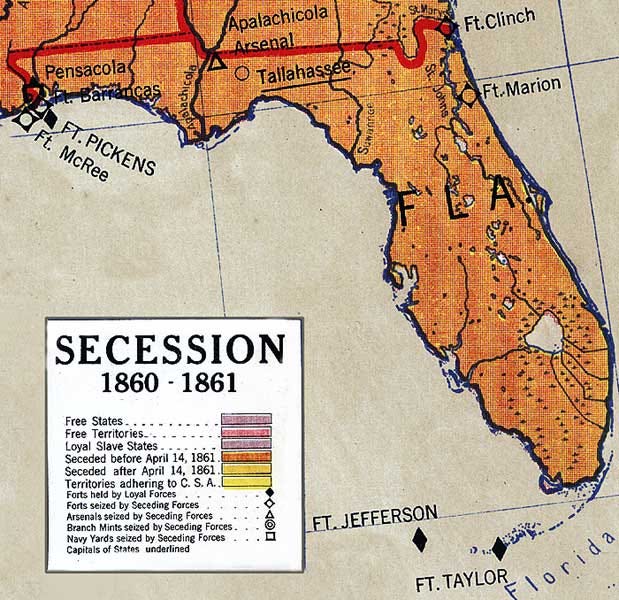

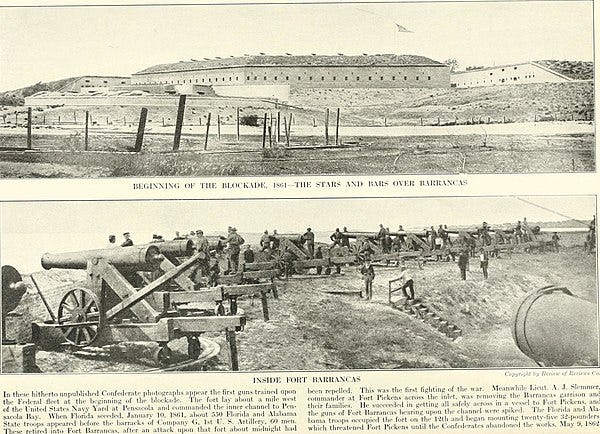

She was born plain Caroline Reynolds in Milford, Delaware, USA, on 26 December 1840, the youngest of four children of John Reynolds, an English-born clergyman ordained in the American Protestant Episcopal Church, and his wife, Eleanor (née Evans) an heiress from Perkiomen, Pennsylvania. The family moved from state to state due to Reverend Reynolds’ preaching work and Caroline, known as ‘Carrie’ to her family, left school at fourteen. Two years later she married Lieutenant Adam J. Slemmer of Norristown, Pennsylvania. She went with him when his company moved to Fort Moultrie in South Carolina, where their son Albert ‘Bertie’ was born, then in autumn 1860 Slemmer was posted to Fort Barrancas overlooking Pensacola Bay in Florida. The Unites States Army was on edge during the winter of 1860-61 as Confederate troops began to organize in the secessionist Southern states. This is what happened when Caroline encouraged her husband to make a stand.

Pensacola Harbor, Florida, 5th January 1861

Twenty-year-old Caroline Slemmer sat down to write to her married sister Ellen Du Puy in Pennsylvania. It was a long letter describing in breathless detail Caroline’s social successes over Christmas and New Year.

‘There never has been so gay a month in my life as the month of December A.D. 1860 and I don’t believe in any other place there could be … We danced Christmas in at Mrs Warrington’s, and we danced Christmas out at a hop given by officers of the ships in port, and every other night we met at some house and danced until morning.

‘You will probably laugh at my silliness when I assure you that at every party your bashful and retiring sister Caroline was undoubtedly the woman whose hand was most sought after in the dance, and whose tongue was most eagerly listened to… To carry away the palm from women much more handsome, much better dressed, much older and more experienced, gives one a pleasant sense of power at the time and leaves no sting afterwards.’1

In the midst of all this (let’s face it) preening there is a note of self-awareness when Caroline admits to her sister that she is simply making the most of things. She was a bright young woman who had gained a husband and child before she had grown up properly herself, and she still craved excitement:

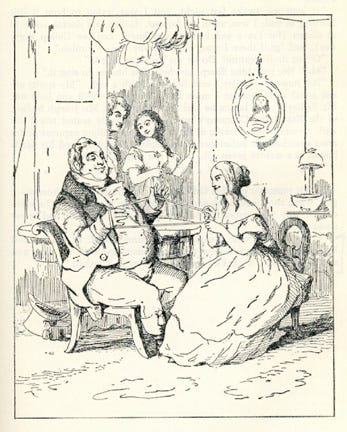

‘That I cannot have the whole cake I realize acutely enough, but I can stay my hunger for happiness now and then, and I should be a fool not to do so… You say I resemble Becky Sharp, and in one or two things, I confess the ‘soft impeachment’, but her worst fault I am free of. She would do anything for money; I, nothing.’

The English author William Thackeray was the well-read Caroline’s favourite living writer and she loved Vanity Fair (1848) more than any other novel. She and the clever, social climbing protagonist Becky Sharp were old acquaintances, she told Ellen, and asks: ‘Don’t you like her better than Amelia?’. She was just about to discuss the ‘intellectual treat’ that was Thackeray’s Henry Esmond (1852) when she heard raised voices outside her door, and put down her pen.

Her husband Adam Slemmer had just convened an emergency meeting of military and naval officers in their house, interrupting Caroline’s letter-writing. The commander and the second in command were both absent on leave (rather suspiciously, given this time of national crisis) leaving Lieutenant Slemmer in charge of Fort Barrancas. This southern military outpost had been built to protect the United States from attacks from the sea, but the problem it was now facing was the very real threat of attack from land. Florida was about to join South Carolina in breaking away from the Union, and reports were coming in that Confederate forces were preparing to take over the strategically important Fort Barrancas along with the nearby Fort McRee and Navy Yard.

With a company of only forty-five men, Slemmer knew that he stood no chance against an armed assault. In any case, his men were reluctant to fire on other soldiers who had been their friends and allies until recently. Should they simply surrender the forts and naval yard to the Confederates, and sail north? Or stay and fight their fellow American countrymen in what would be a hopeless battle? The discussions went on for a very long time, until after several hours of listening to the men, Caroline could stand it no more. Jumping to her feet, she said: ‘Well, if you men will not defend your country’s flag, I will!’

Caroline’s heroic enthusiasm settled the matter for the men, it seems. Lt. Slemmer decided to leave Fort Barrancas and move his men who were loyal to the Union to Fort Pickens, a smaller fortification on Santa Rosa island just off the coast, and defend it against Confederate forces until reinforcements came. Before leaving, his company destroyed over 20,000 pounds of gunpowder at Fort McRee and spiked the guns at Fort Barrancas. Then 51 soldiers and 30 sailors sailed the short distance to Santa Rosa Island. On 10th January Florida became the third state to secede from the Union and on January 12th, rebel troops from Alabama and Florida occupied the Navy Yard and Fort Barrancas.

‘Well, if you men will not defend your country’s flag, I will!’

Meanwhile, the army wives had packed up their luggage and set sail with their children and servants to New York, but the most exciting part of Caroline’s war was just about to begin. When she got to New York she found that exciting rumours about her bravery at Fort Barrancas were already circulating. One newspaper headline read ‘MRS SLEMMER ARRESTED AS SPY’. It was reported, thrillingly, that she had tried to gain access to Fort Barrancas to take notes and report back to her husband. Caroline’s version of events was more pragmatic. She told a reporter that before leaving Pensacola she had tried to go back into the barracks to fetch some of her husband’s clothes, and when access was denied she had threatened to return and man one of the guns herself.

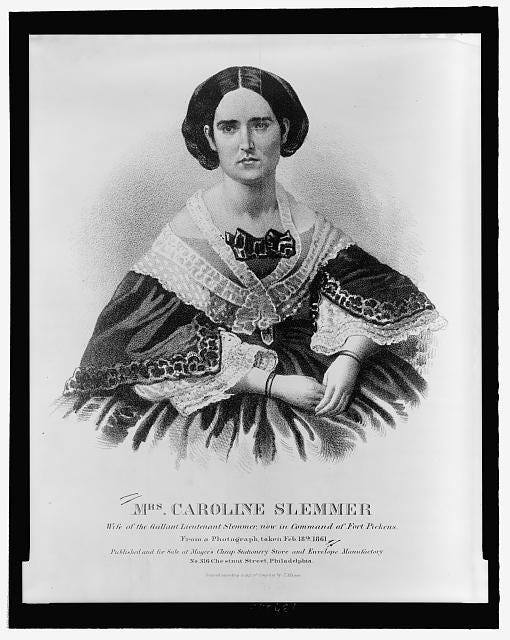

But the public craved more stories of her bravery. On 9th February the personal column of Harper’s Weekly stated: ‘The gallantry exhibited by the wife of Lt. Slemmer, at Pensacola, is creating quite a lively sensation among the patriotic ladies at Washington. A suitable testimonial in her behalf is in contemplation.’ On 16th February another newspaper breathlessly reported that ‘in face and feature she is extremely prepossessing, with very captivating manners. She is worthy to be the wife of an American soldier’.

Caroline had become a war heroine before the war had even officially begun, and she posed, looking beautiful and imperious, for a photographic portrait. It became, in effect, a patriotic pin-up, with cheap prints of it advertised for sale with the inscription: ‘Wife of the gallant Lieut. Slemmer, now in command of Fort Pickens’.

But what about her gallant husband? For months, Adam Slemmer and his men bravely defended Fort Pickens against an invasion which never happened. Even so, they were constantly under attack: Santa Rosa Island was infested with rattlesnakes and vipers, and with little access to fresh food, scurvy was a constant threat. But despite Confederate threats, an uneasy truce remained in place until April 1861, when Slemmer’s company was relieved at last. Their noble stance had been gruelling, but not entirely in vain; Fort Pickens was one of the few Southern forts to remain in Union hands throughout the Civil War, and was an important base in the Gulf of Mexico during the blockade of the Southern states.

At the end of the siege, before her husband returned to Pennsylvania, Caroline felt aggrieved to discover that Adam was still a mere Lieutenant, especially as, since the outbreak of the Civil War, less experienced men had been given commissions in the ten new regiments. On 10 May 1861 she wrote to President Abraham Lincoln directly, suggesting that her husband be promoted to the rank of captain or major for his services to his country: ‘in Lieut. Slemmer’s absence, at Fort Pickens, when, on account of that absence, he cannot attend to his own interests here, I trust it will not appear unfeminine if his wife endeavors to take that duty on herself’.

‘I trust it will not appear unfeminine if his wife endeavors to take that duty on herself’

Shortly afterwards, Caroline was given an appointment at the White House. In her memoir Period Piece (1952) Caroline’s great-niece Gwen Raverat, who knew her as ‘Aunt Cara’, takes up the story, which she must have heard many times.

She went, with her two brothers-in-law, to an arranged interview with the President; saying to herself, ‘After all, he’s only a man like any other,’ by which she meant that, of course, she could get him to do what she wanted. They found the President sitting at a writing table; at first the conversation was rather halting, but presently Aunt Cara, who was standing beside him, laid her hand lightly on his shoulder, as she put forward her plea. Mr. Lincoln smiled, and gently placed his hand on hers for a moment, and the ice was broken.

This wartime manoeuvre of Caroline’s was another success. In the Abraham Lincoln papers at the Library of Congress there is a scribbled note in Lincoln’s handwriting:

‘List of officers I wish to remember when I make appointments for Officers of the Regular Army – Maj. Doubleday, Maj. Anderson, Capt. Forster, Maj. Hunter, Lieut. Slemmer – his pretty wife says a Major or First Captain.’

Caroline had proved to herself that she could charm the most important man in the land into doing what she wanted, even when he had a Civil War to think about. Her heroine Becky Sharp would have been impressed.

An invasion of croquet

On this day in 1904, the English author, historian and biographer Sir Leslie Stephen (1832-1904) died. He was a co-founder of the Alpine Club and the Dictionary of National Biography, among other achievements, but is perhaps best known today for being the father of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell. Their mother Julia Duckworth was Stephen’s second wife, …

The Cambridge bride

On the way to a lovely summer wedding held in an English country garden last weekend, I spotted a bride and groom sitting on a bench at the Baker Street stop on the London Underground. As I took a snap of the happy couple (in a ray of celestial light from the window above) there was an audible ‘Aaaah!’ from the other train passengers who were also happy to witness a romantic kiss. Over one thousand people on Substack Notes have now enjoyed and commented on my photo, and it’s given risen to some intriguing theories of why the bride and groom picked this spot: was it a tribute to Sherlock or due to the proximity to Marylebone Registry Office? Did the couple first meet there, and will they celebrate their first anniversary by returning to this spot? (Click on the image below to find out more…)

Sources

Lady Caroline Lane Reynolds Slemmer Jebb Papers, 1858-1960 at the Sophia Smith Collection and Smith College Archives, Smith College, Northampton MA (with thanks to Karen Kukil); The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress; American Battlefield Trust website, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/pensacola-1861.

Mary Reed Bobbitt, With Dearest Love to All: The Life and Letters of Lady Jebb (London: Faber, 1960); Peter J. Parish, The American Civil War (London: Eyre Methuen, 1975); Gwen Raverat, Period Piece (Faber and Faber, 1952).

Further reading

On the subject of money in fiction, I’ve recently enjoyed

on heiresses in Jane Austen’s fiction; Thackeray’s The History of Pendennis explored by (‘all the principal women here… far from being supine, have a shared steeliness’); on Zora Neale Hurston’s rise and fall during her lifetime; and on financial shenanigans in P.G. Wodehouse’s Big Money (1931). I’d love to know if there are any novels you would recommend that explore the subject of money, especially women and money, in interesting ways.

This is riveting! There will be more coming on her, I hope?

I love how the Thackeray bits are woven in, and it was a delight to see the Gwen Raverat connection unexpectedly appear.

On the thing with the flag: there's a famous couplet in a US poem about a woman standing up for the flag: ““Shoot, if you must, this old gray head,/But spare your country’s flag,” she said.” (https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45483/barbara-frietchie)

I had mistakenly remembered it as being from the Revolutionary War, and thought that Cara might have been semi-quoting it. But it seems that the poem was written in 1863, about a Civil War event, and now I wonder if the poet, John Greenleaf Whittier, although basing the text on a real person (it seems the incident itself might or might not have happened) wasn't thinking back to Cara's line, if that was widely reported and discussed a few years earlier.

I've just seen your incredibly kind mention of my recent post... thank you Ann! Very much appreciated.

Longing for more of these extraordinary back stories.