Hello and welcome to Cambridge Ladies Dining Society. This week, as pencils are sharpened and schoolbags are dusted off in preparation for the new term at colleges and universities, I wanted to introduce the remarkable intellectual discussion group of twelve Victorian women that this publication is named after. They were all married to Cambridge University professors and college Masters, but they didn’t want to be just dutiful academic wives. These quietly radical women who settled in Cambridge in the 1870s and 1880s wanted to make a difference, and together they decided to do things their own, non-traditional way. It starts with an imaginary section, setting the scene…

The professors were left to fend for themselves for the evening. Some drifted off happily to dine in their respective colleges, thinking about important matters to be discussed. Others were having solitary suppers in their studies, books and papers piled up around them. Their wives had arranged the suppers, given detailed instructions to cooks and servants, written letters and lists, and made all the arrangements. Then they put on their evening dresses and jewellery, gathered up their notes, and set off on foot, by cab or even on bicycles. Shortly afterwards, these twelve Cambridge women sat down to dinner together. Their own evening had begun at last.

In 1890, Louise Creighton and Kathleen Lyttelton, both published writers who happened to be married to Cambridge dons, decided to form a dining and discussion club of their own. They invited a select group of nine of their women friends to join (later Ellen Darwin became the twelfth member). ‘Not without an idea of retaliating on the husbands who dined in College’1 – wives were not permitted to dine at High Table – these enterprising women agreed to take it in turn to arrange a dinner once a term and choose a suitable subject for serious discussion.

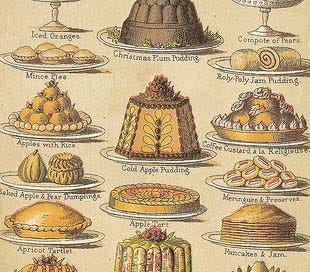

‘The hostess not only provided a good dinner (though champagne was not allowed),’ recalled Mary Paley Marshall, ‘but also a suitable topic of conversation, should one be required, and she was allowed to introduce an outside lady at her dinner; but it was an exclusive society, for one black ball was enough to exclude a proposed new member.’

They called themselves the ‘Ladies’ Dining Society’, a name that sounds rather quaint and privileged nowadays. But forming a society of their own was an act of rebelliousness all the same. In 1890, when the club began, Cambridge University was still very much a male world, with its few (unofficial) female students, lecturers and college workers living in colleges outside the town. Women had always been part of university life, of course but only as poorly paid domestic servants and ‘bedders’ (cleaners).

In 1882 the university dropped an ancient statute forbidding college fellows from marrying (yes, until then they really were expected to live like monks). The first generation of academics’ wives who arrived in Cambridge were ‘welcomed’ in a rather bizarre ritual, then expected to remain in the background. Their main duty as a wife was to host elaborate formal dinner parties for senior university members and their wives. These women, who were often highly educated themselves, were excluded from their husbands’ colleges and the discussions that went on there.

The Ladies’ Dining Society agreed to gather together once or twice a term from 1890 until 1914, with the topic of discussion arranged in advance. It was, in the words of the economist John Maynard Keynes, ‘a remarkable group’. Its twelve women members were all high achievers in their own right, including Mary Paley Marshall (1850-1944) was one of Cambridge’s first women students who would later co-found the Marshall Library of Economics; Mary Ward (1851-1933) fought for women’s degrees in 1897 (see my post here) and became a leading suffragist playwright. The American Caroline Jebb (1840-1930), who was also an influential supporter of suffrage, wrote brilliant letters about her life in Cambridge and became an insightful biographer.

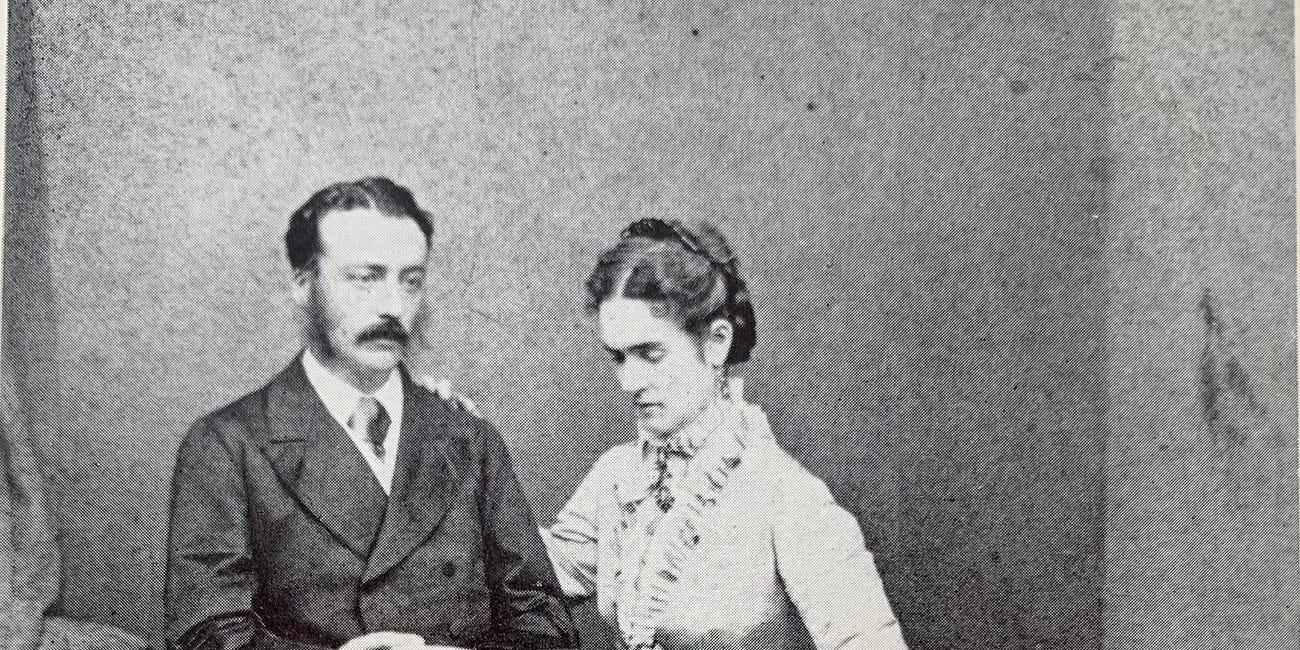

Maud Darwin (1861-1947) campaigned for the introduction of women police officers in Britain during the First World War, while Ida Darwin (1854-1946) to later lent her support to make a radical new form of mental healthcare, based on talking therapies for shellshocked WW1 soldiers, available to ordinary people in peacetime. Kathleen Lyttelton (1856-1907), who looks so languid in the portrait above, was in fact a powerhouse of feminist activism and an influential suffragist who later became the editor of a women’s pages section in a national newspaper. She was the first editor to commission, and pay for, book reviews by a young Virginia Stephen, and Woolf never forgot the thrill of her first pay cheque.

‘The Ladies’ Dining Society was a testament to friendship and intellectual debate at a time when women’s voices went largely unheard.’ Ann Kennedy Smith, ODNB

Virginia Woolf once called Cambridge ‘that detestable place’ for denying educational opportunities to female students and scholars. But these quietly radical women worked together to make a difference to the lives of others, and their influence went far beyond college walls.

For almost twenty-five years, from 1890 to 1914, the Ladies’ Dining Society provided a network of friendship and a space for debate in Cambridge where women’s voices would be heard, and it helped to give its members the support and inspiration they needed to take on bigger challenges. I’ll be exploring more of their stories in future posts.

Thank you so much for reading this post. I hope you have a good new start of term, in whatever form that takes. Next week’s piece will be about a more shameful aspect of Cambridge University’s past, when during the nineteenth century ancient laws allowed proctors to arrest and imprison unchaperoned women found walking the streets of Cambridge after dark. A new book throws light on that dark history.

Joseph Johnson's modern dining club

In late 18th century London there was a little-known, but influential, dining club for writers, artists, political thinkers and scientists hosted by publisher and patron of the arts, Joseph Johnson. He is the subject of biographer Daisy Hay’s new book,

Further reading: Ann Kennedy Smith, ‘Ladies Dining Society’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 9 May 2018 (available online in many public libraries); the Wiki entry here is based on my research. ‘The Rising Tide: Women at Cambridge’ (online article about the 2019-2020 exhibition at Cambridge University Library); Mary Paley Marshall, What I Remember (1947); Linda Hughes, ‘A Club of Their Own: The “Literary Ladies,” New Women Writers, and Fin-de-Siècle Authorship’ (Victorian Literature and Culture Vol. 35, Issue 1, March 2007, pp. 233-260.

The Cambridge bride

On the way to a lovely summer wedding held in an English country garden last weekend, I spotted a bride and groom sitting on a bench at the Baker Street stop on the London Underground. As I took a snap of the happy couple (in a ray of celestial light from the window above) there was an audible ‘Aaaah!’ from the other train passengers who were also happy to witness a romantic kiss. Over one thousand people on Substack Notes have now enjoyed and commented on my photo, and it’s given risen to some intriguing theories of why the bride and groom picked this spot: was it a tribute to Sherlock or due to the proximity to Marylebone Registry Office? Did the couple first meet there, and will they celebrate their first anniversary by returning to this spot? (Click on the image below to find out more…)

E. Sidgwick, Mrs Henry Sidgwick: a memoir by her niece (1938), p. 115.

I loved reading this résumé of the Ladies' Dining Society, but of course I'm biased! Kathleen Lyttelton also became the President of The National Union of Women Workers in 1901 and 1902. Thank you Ann for writing about the Society.

This is, as ever, so interesting. But...DONS WEREN'T ALLOWED TO MARRY? We have already read about how WOMEN WEREN'T ALLOWED TO TAKE DEGREES. What kind of education was anyone able to receive, when the people in charge of providing it were clearly insane?