French invasions and other battles

Alfred and Emily Tennyson's secret war poems

Hello! It’s another balmy April day here in Cambridge, and although this weather surely won’t last for much longer, pink cherry blossom is still on riotous display, making the solemn college stonework look very pretty. A few weeks ago I asked for suggestions for ‘Hidden women in history’ and was delighted to receive lots of wonderful nominations in the comments and via email. One was for Emily Tennyson (1813-1896), whose biography by Ann Thwaite happens to be one of my all-time favourites, and really opened my eyes to how certain myths prevail about Victorian middle-class women. So here’s my essay about a difficult time in the early married life of the Tennysons, and how Emily’s strength and character helped to get them through it. (Virginia Woolf really did underestimate her.)

French invasions and other battles

January, 1852: England’s Poet Laureate, Alfred Tennyson, sits alone in the library of his mother’s house in Cheltenham. It is late at night and the rest of the family are asleep. He is a tall, broad-shouldered man with loose dark hair and dishevelled appearance, once strikingly handsome, but who now – with his hollow cheeks, ghostly pallor and spectacles – looks much older than his forty-one years. He is tired, but too worried to sleep. For the past eighteen months he has been battling with a clutch of personal demons. His sudden success as a poet after so many years, the pressures of the laureateship and fame, his late marriage to Emily and the death of their infant son, all have made him unsettled and unable to write.

In the winter of 1851-52 the English newspapers were full of reports of Louis Napoleon’s seizing of power in France, and rumours that he might be planning to invade England next. Tennyson knew that a hundred miles away, at their home in Twickenham, his newly pregnant wife Emily would be lying awake, worrying. On that January night, he decided that – as the poet of England, and for Emily’s sake – he had to act. He took out a sheet of paper, and stooping over the page, started to write in ‘a white heat of emotion’, tears streaming down his face. The poems that emerged were so provocative and shocking that many admirers of his work wish they had never been written. But without them, Tennyson might not have gone on to write Maud (1855) his vast and subtle poem of war and peace.

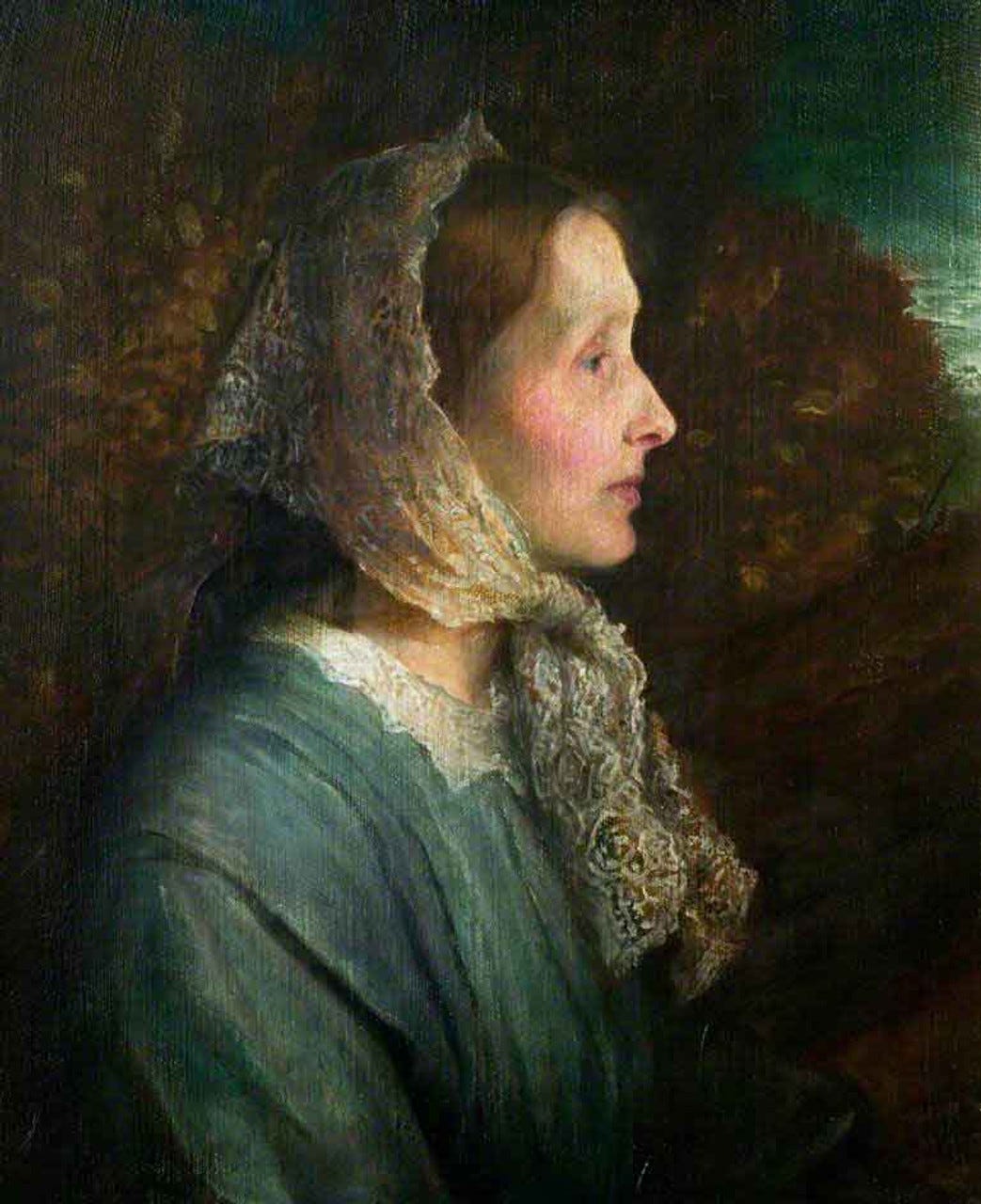

1850 was a remarkable year for Tennyson. On 1 June In Memoriam A.H.H., his collection of lyrics mourning the death of his great friend, the poet Arthur Henry Hallam (1811 – 1833), was published and became an immediate bestseller. Less than two weeks later, Alfred Tennyson and Emily Sellwood, 35, got married. Although they had known each other for over twenty years (and been engaged before), the marriage came as a surprise to most of his friends, who did not see the forty-year-old poet as ever likely to settle down. Thomas Carlyle was not impressed by Emily’s appearance when he first met her, describing her as a rather ordinary-looking, shapeless woman with a round, freckly face. But when he started talking to her, he was immediately struck by how her ‘bright glittering blue eyes’ lit up, and how her conversation revealed her good sense and intelligence.

A few months later, in November 1850, another redoubtable lady, Queen Victoria, made Tennyson an offer he felt he could not ‘gracefully’ refuse: the official position of Poet Laureate. He was aware that it would mean certain expectations of him as a poet, as well as a fair amount of ribbing from his friends. Poet Laureates were no longer expected to write things like birthday odes for the Queen, he reasoned, but what sort of poems should a royally approved poet write?

After being awarded the laureateship Tennyson went through a bad case of writer’s block. There was little time to write, in any case; following their marriage, he and Emily travelled about the country for months, staying with family and friends. In mid-January 1851, with Emily expecting their first baby, they moved into their first home in rural Sussex, but impulsively left it two weeks later, unable to stand the house’s remoteness, susceptibility to storms and superstitious associations any longer.

In March 1851 they moved to Twickenham, then a sleepy rural village eleven miles from London. Chapel House was at the end of Montpelier Row, a beautiful early eighteenth-century terrace near the river. Tennyson had been delighted with the house on first sight, describing it in a letter to Emily as full of light and views of gracious parkland from every room at the top, adding that ‘the only objection I have to it is its nearness to London: which is rather a horror to me’.

He was right to worry, as it turned out; the railway had arrived in Twickenham three years earlier and it was all too easy for friends from London to call on them, so their peace was frequently invaded. Also, despite the spacious park nearby, it was not long before the confined nature of suburban life began to affect Tennyson, a man who since his youth had never stayed in one place for long. Emily noted anxiously in her journal: ‘Alfred walks before breakfast… Duty walks and alas! without pleasure.’

Then, on Easter Sunday 1851, tragedy struck. Their first child, a boy, died at birth. Rather than announce it in The Times, Tennyson wrote over sixty letters to friends in the following days, movingly describing how his infant son’s hands were clenched as if in fierce determination to be born: ‘he looked, I thought, as if he had had a battle for his life’. A few months later, as soon as Emily was well enough, she and Tennyson travelled to the Continent, hoping to spend the winter in southern Italy. Their longed-for escape was cut short, much to her disappointment, when bad weather made it too stormy to take the boat to Rome or Naples and worrying rumours reached them of civil unrest brewing in the Italian countryside.

‘He looked, I thought, as if he had had a battle for his life’

They returned to Twickenham and ‘rather a melancholy house’, as Emily put it. Tennyson could not settle. Franklin Lushington astutely observed that ‘Alfred Tennyson is naturally in a restless state of mind which impels him to quit Twickenham and get a house in some remote part of the country, from which of course he would be equally anxious to return again into the neighbourhood of London’. Before finding Farringford on the Isle of Wight, both Tennysons must have privately wondered if they would ever find a home they loved.

Then on December 3 1851 everything changed. Reports started coming in from France that the government had been overthrown in a coup d’état by Louis Napoleon, the ambitious nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte. The London Times gloomily reported the news as if it was only to be expected, announcing: ‘The French Revolution has once more resumed its eccentric and irresistible course.’ This was not the beginning of another republic, however, but the first days of France’s twenty-year long Second Empire. Louis Napoleon, soon to crown himself Emperor Napoleon III, made no secret of his militaristic ambitions, and when he referred to ‘repairing the damage to national self-esteem’ inflicted by the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, many English people took this literally as a sign that he was planning another war with them.

Throughout January and February 1852 English newspapers stoked these fears, publishing ever more pessimistic reports from France and frightening predictions of an imminent invasion. The letters pages bristled with criticisms of the British government’s political manouverings that had favoured fat-cat business interests over national security, risking the safety of its own people:

We also take no care for the fortification of our country or the equipment of our troops. We arm them with weapons that are all but harmless… We view without apprehension an enormous military Power beside us, assuming a position that renders foreign war almost a necessity of existence.

With an ill-equipped British army too busy fighting overseas to defend their own country from the threat of imminent French invasion, the idea of self-defence quickly gained hold among many newspaper readers. There were calls for rifles to be distributed so that every man could defend his home and family, and volunteer rifle clubs began to spring up around the country. Even poets were not immune from the general fervour. The poet Coventry Patmore organized his own rifle club at the British Museum, where he worked, and Emily and Alfred Tennyson were both happy to hand over £5 each to help their friend to buy rifles.

This was not the first invasion scare to grip the nation. Only three years before, the 1848 upheavals on the Continent and another revolution in France had sent a collective shudder through England. In 1849, in an effort to counter the prevailing English distrust and dislike of foreigners, Prince Albert threw his weight behind plans for a ‘Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations’, to be held in Hyde Park, London. The Great International Exhibition of 1851 was opened by Queen Victoria on May 1st 1851, and Joseph Paxton’s vast purpose-built structure was dubbed ‘the Crystal Palace’ by Punch magazine. It was the first large-scale show of its kind, showcasing the latest technical innovations and aimed at promoting peace and foreign trade among nations. With over six million people from Britain and overseas pouring through its doors for the six months it lasted, the Great Exhibition was hailed as a triumph for pacifist internationalism.

However, there were some unintended consequences. The exhibition inadvertently caused a notable surge in English nationalism by highlighting the differences between Britain and the rest of the world. One Punch cartoon of the time shows three dishevelled Frenchmen standing outside the Crystal Palace, gazing at a display of washbasins and bars of soap and wondering aloud what they could be used for. The contrast with the neatly top-hatted Victorian English gentleman next to them underlined the message that there was an unbreachable gulf between the two nations.

More seriously, in his great poem ‘Dover Beach’ written this year, Matthew Arnold expressed the uneasy sense that the mid-century’s peace was only a brief lull in the more usual state of international conflict, and England and France might easily be drawn back to a darker time ‘where ignorant armies clash by night’. Peace among nations in 1851 seemed, like the glass Crystal Palace itself, fragile and temporary.

Tennyson, who was old enough to remember the first Napoleon and the 1830 revolution in France, had always had his suspicions about the French. But exactly how fearful was he in January 1852 ? It’s worth remembering that at the height of the crisis, he went to visit his family in Cheltenham, leaving Emily, newly pregnant again and too unwell to travel, at home. His mother, sister and brothers lived in an elegant three-storey townhouse in St James’ Square, and Tennyson’s sister Mary and her lawyer husband would soon be emigrating to the West Indies. There were dutiful calls to be made and dinners to be eaten.

But one night, alone, Tennyson’s fears and dissatisfaction with English life surfaced and he began to write the first of an extraordinary series of seven patriotic poems which were published anonymously or pseudonymously in The Examiner and other newspapers in January and early February 1852.

‘Very wild but I think too savage!’

A weapon, a game, a kiss

This week’s TLS features two newly discovered poems by Virginia Woolf. Perhaps it’s generous to call them poems. Sophie Oliver, the UK academic who found them in a folder of letters to Woolf’s niece, Angelica Garnett (née Bell) describes them as ‘doggerel’. It’s probably fair to say that they are not likely to be included in any poetry anthologies, that doesn’t mean that these scribbled verses are not significant. Oliver argues that the point of such verse for Woolf was ‘to play, poke and charm, and to help with what Angelica thought was one of her aunt’s greatest gifts, creating intimacy with people.’

‘The Penny-Wise’ or ‘Arm!’, begins with a stark warning:

O where is he, the simple fool,/ Who says that wars are over?/ What bloody portent flashes there/ Across the straits of Dover?

It urges ‘Britons all’ to arm themselves and prepare to fight the ‘barbarians better-armed’ in the approaching ‘battle of the world’. It is not hard to imagine an insomniac Tennyson writing this in the middle of the night, as ‘sleepy Lords of Admiralty’ and ‘many a dreamer’ alike are urged to ‘wake, arise’ and be ‘up, now, and be doing’.

Another poem written in Cheltenham, ‘Riflemen Form!’, features the anti-French lines ‘Bearded monkeys of lust and blood/ Coming to violate woman and child!’ Tennyson sent it to his friend Coventry Patmore to arrange publication on strictly anonymous terms, scribbling (with sounds like childish glee) at the end, ‘Very wild but I think too savage! Written in about 2 minutes! My wife thinks it too insulting to the F[rench] and too inflaming to the English.’

It is not difficult to see why Emily might have urged a little restraint. The poems are jingoistic, xenophobic and anti-Catholic, a far cry from both Tennyson’s sensitive, lyrical In Memoriam and the dutiful ‘To the Queen’, the only new poem he had written since becoming Poet Laureate.

These were poems written as much to vanquish his own demons as to provoke his fellow countrymen to arms.

The excitable titles and liberally scattered exclamation marks of these 1852 poems give a good indication of their fiercely nationalistic contents: ‘Britons, Guard your Own’, ‘Arm, arm, arm!’ and ‘Hands All Round!’. Tennyson knew that their coarse language and bloodthirsty sentiments made them not at all appropriate for a Poet Laureate, but he did not care. In fact, he seemed to rather enjoy it. It is almost as if, in his mind, the hordes of invading Frenchmen were surrogates for all the emotions that had tormented him since fame, the laureateship and marriage had come along to disturb him. These were poems written as much to vanquish his own demons as to provoke his fellow countrymen to arms.

It’s the first time that we get an indication of how closely Emily was involved in Tennyson’s work. In her letters to friends and editors at this time she starts to use ‘we’ and ‘our’ unselfconsciously about her husband’s poetry and it is evident from what she wrote that they worked closely together from then on. The caricature of Emily as a frail, sofa-bound invalid wife has persisted. The famous perpetrator of this myth was Virginia Woolf, who in her farce Freshwater wrote:

‘Emily jump? Emily jump? She has lain on her sofa for fifty years. She took to it on her honeymoon, and I should be surprised, nay I should be shocked, if she ever got up again.’

It is true that Emily’s health was poor; she suffered from a painful back and twenty years later became permanently disabled, but even then she never stopped working and discussing everything with Tennyson.

In 1852, despite being in the early stages of pregnancy, her mental and physical energy is striking. As well as donating her own money to Patmore to buy rifles, while Tennyson was away she became actively involved in the cause of English self-defence, writing persuasive letters to their friends to galvanize support, distributing leaflets and issuing invitations to fundraising dinners. She was also dealing with her husband’s publishers, in her charmingly no-nonsense way, aware that their well-connected friends were likely to read the same newspapers and gossip about the authorship of these contentious poems.

She and Tennyson discussed the rather thrilling risk of Tennyson’s name reaching the ears of Louis Napoleon himself, or that Queen Victoria might be forced to have a word with her trouble-making Poet Laureate. It was Emily who wrote to John Forster, the Examiner’s editor, to ensure that Tennyson’s name was kept secret, and to Coventry Patmore asking him never to refer to Tennyson as an ‘agitator’ because, as she put it, ‘the word has come to have so evil a meaning, a sort of hysterical lady meaning if nothing worse’.

‘the word has come to have so evil a meaning, a sort of hysterical lady meaning’

Although pragmatic and protective of her husband’s reputation, Emily was certainly no hysterical lady herself, but passionately concerned with contemporary events. There is a tiny but telling detail in a letter Tennyson wrote to her at this time, in which he mentions his irritation with The Times and asks rather plaintively ‘Must thou read it every day?’1 Was he asking her to stop reading the newspaper because she was lying awake at night worrying about it all?

Unfortunately, most of Emily’s letters have been lost or destroyed, and her published journal is incomplete. But if we look at the entries that she wrote two years later at the height of the Crimean War, when England allied with France and Turkey to fight Russia, we can see how fascinated she was by the reports she read in The Times. In November 1854 it was Emily who carefully noted down the vivid descriptions of the soldiers’ sufferings filed by William Howard Russell, the first great war correspondent:

We read that touching account of the Scotts Grays &… how they devoted themselves at Balaclava. The writer says that their “ears are frenzied by the monotonous, incessant cannonade going on for days altogether”. Some Captain compares the appearance of the troops to the turning of a shoal of mackerel. We are almost afraid to open the newspapers now.

Both Emily and Tennyson were ‘afraid’ to open the newspapers, as she put it, because the details of the fighting consumed them and they could talk of little else. It was after reading Howard Russell’s words that Tennyson wrote ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’, with the famous line ‘Someone had blundered’. It is one of his best known poems, and expresses a compassion for the dignity and courage of the soldiers on their doomed mission that millions of readers still find moving today.

The patriotic poems of 1852 are comically clumsy by comparison, but they were, effectively, Alfred and Emily Tennyson’s first joint production They were written when they were physically apart but communicating daily by letter. It was a time of uncertainty in their marriage, in a home they did not love, grieving the death of their first baby and not knowing if the next one would survive, besieged by well-meaning friends and visitors. Writing and publishing the poems in secret together cemented their private bond.

Reviewing the 1969 edition of Tennyson’s collected poetry, Philip Larkin wrote that reading the complete works was like entering a delightfully picturesque Victorian landscape until suddenly ‘we are brought up sharp… by the assertive trumpets of imperial patriotism’. This strident political poetry sits uneasily with what we know, or think we know, about Tennyson and it seems a far cry from the famous words from ‘Ulysses’ chosen to inspire international athletes at the 2012 London Olympics: ‘To strive, to seek, to find and not to yield’.

‘To strive, to seek, to find and not to yield’

Tennyson’s biographers, from his son Hallam onwards (whose Memoir of his father was co-written with Emily), have been embarrassed by what he produced in early 1852, dismissing these poems as ‘the hollow belligerence of the unmartial man caught up in blind chauvinism’. Hallam implies that his mild-mannered mother was temporarily, and rather helplessly, caught up in her husband’s hysteria. In fact, Emily was as enthusiastic as Alfred was was about defending England, and despite the risks she encouraged him to write the poems as a matter of national importance.

Exaggerated and belligerent as they might seem to us now, the patriotic poems represent an important aspect of Tennyson’s work, when he managed with the help of Emily to break through his writer’s block and rediscover his poetic voice. Larkin would not have stumbled across them today, because these poems have now been dropped from the latest edition of Tennyson’s collected poetry. It is perhaps not surprising that modern editors have suppressed such fierce, politically incorrect poems (even though like the line from ‘Ulysses’ they are essentially about finding the courage to fight real or imaginary demons).

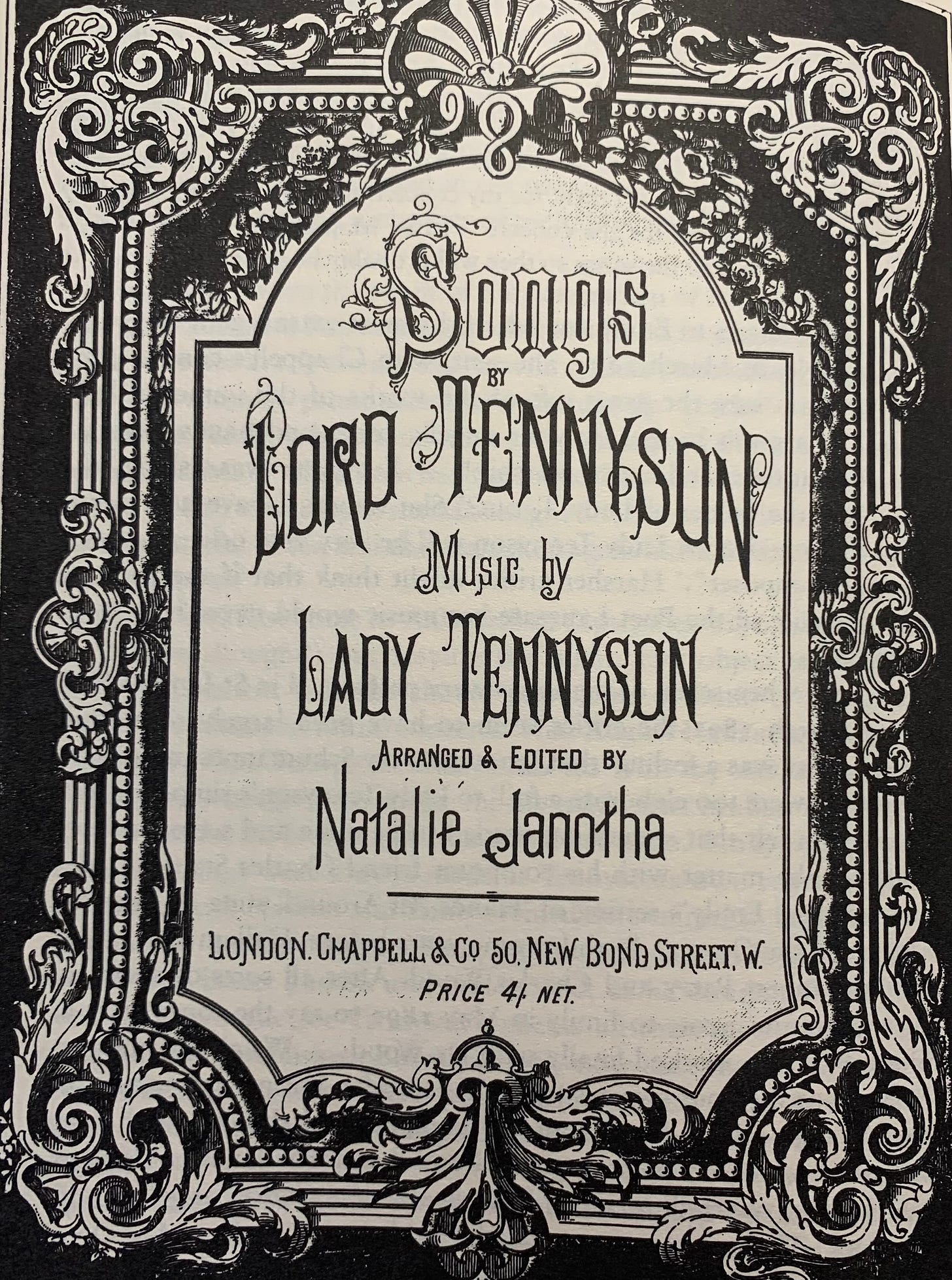

If we choose to overlook the war poems in the future it will be easy to do, and might make Alfred Lord Tennyson more appealing as a poet. But how and why these poems were written tells us something important about the time, Tennyson’s development as a poet and Emily Sellwood Tennyson’s own, much less documented story. She was a composer in her own right, and later removed much of the anti-French invective of the patriotic poems when she set the poems to music. “Hands All Round’ was used to celebrate Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee in 1897, and it was Emily’s version of Tennyson’s Patriotic Poems that was published in a pocket-sized version in 1914 for British soldiers to take with them into battle, where they fought alongside their French allies.

Postscript: Emily gave birth to two healthy sons: Hallam, born in Twickenham in August 1852 and Lionel, who was born in March 1854 in Farringford on the Isle of Wight, which became the Tennysons’ much-loved permanent home.

Not Afraid of Virginia Woolf

In 1928, a twenty-year-old student called Elsie Phare (later known as E.E. Duncan-Jones) wrote to Virginia Woolf, inviting her to give a talk on the subject of women and fiction to the Arts Society at Newnham College, Cambridge. The society’s president Elsie Phare was in her second year studying English Literature, so it must have been thrilling when one of the great modernist writers of the time provisionally accepted the invitation (the following year T.S. Eliot politely turned her down). The success of Virginia Woolf’s

Notes

My thanks to U.E.A. for awarding me the 2014-15 biography and creative nonfiction Master’s scholarship based on this essay, and to Ann Thwaite for her wonderful Emily Tennyson: The Poet’s Wife (Faber, 1996) which inspired me to do this research. A new, updated version of this is forthcoming from Baylor University Press. I am also very grateful to the Tennyson Society for their support, and to Andrew Hewitt for his generous writing advice. Any remaining errors are my own.

‘tall, broad-shouldered…’ from William Allingham’s Diaries in Bevis, pp. 251–2; ‘in a white heat of emotion…tears streaming’: Charles Tennyson, p. 266

‘bright glittering blue eyes’ Thomas Carlyle to Jane Welsh Carlyle, Alfred Tennyson (AT) Letters I, p. 339; ‘the most lovely house…’

AT Letters II, p. 3; ‘the only objection’ AT Letters II, p. 1; ‘Alfred walks…’ Lady Tennyson’s Journal, p. 26; ‘as if he had had a battle for his life’, AT, Letters II, p. 14

‘rather a melancholy house’, letter from Emily quoted in Thwaite, p. 239

‘Alfred Tennyson is naturally in a restless state of mind’ Franklin Lushington to William Henry Brookfield, Letters II, p. 26

‘The French Revolution has once more resumed…’ The Times, 3 December 1851

‘We also take no care…’ The Times, 8 January 1852

Punch cartoon, see Auerbach, p. 184

Matthew Arnold, ‘Dover Beach’, see Victorian Web

‘Very wild…’, AT Letters, II, 21

‘Emily jump?’, quoted in Thwaite, p. xv

Page 4: ‘agitator … hysterical lady meaning’, Emily Sellwood to Coventry Patmore, Letters, II, p. 25

‘We read that touching account’ Lady Tennyson’s Journal, p. 26

‘we are brought up sharp’, Philip Larkin, ‘The Most Victorian Laureate’, New Statesman, vol. 77, 14 March 1969, pp. 363–4

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/emily-tennyson-18131896-wife-of-alfred-tennyson-82131

Works consulted

Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Letters: The Letters of Alfred Lord Tennyson, 3 vols, edited by Cecil Y. Lang and Edgar F. Shannon, Jr (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982–90)

Auerbach, Jeffrey A., The Great Exhibition of 1851: A Nation on Display (New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1999)

Bernard Martin, Robert, Tennyson: The Unquiet Heart (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980)

Bevis, Matthew, Lives of Victorian Literary Figures 1: Alfred Lord Tennyson (London: Pickering and Chatto, 2003)

, Emily, Lady Tennyson: The Poet’s Wife (article on Substack, December 1st 2023)– Literature for the People: How The Pioneering Macmillan Brothers Built a Publishing Powerhouse (Pan Macmillan, 2024)

Kennedy Smith, Ann, 'Tennyson’s French Reception' in The Reception of Alfred Tennyson in Europe, edited by Leonee Ormond (Bloomsbury Academic, 2017)

– ‘Tennyson seen from there: Enoch Arden’s French reception’ in The Tennyson Research Bulletin,10.3, pp. 251–265 , 2014

Alfred Tennyson, Poems, 3 vols, edited by Christopher Ricks

– The Letters of Alfred Lord Tennyson, 3 vols, edited by Cecil Y. Lang and Edgar F. Shannon, Jr (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982–90)

– Tennyson, A Selected Edition, edited by Christopher Ricks (Harlow: Pearson, 2007)

Tennyson, Charles, Alfred Tennyson, by his grandson Charles Tennyson (London: Macmillan, 1968)

Tennyson, Hallam, Alfred Lord Tennyson, A Memoir, by his son, 2 vols (London: Macmillan, 1897)

Tennyson, Emily, The Letters of Emily Lady Tennyson, edited by James O. Hoge (1974)

– Lady Tennyson’s Journal, edited by James O. Hoge (Charlottesville, University Press of Virginia, 1981)

Thwaite, Ann, Emily Tennyson: The Poet’s Wife (London: Faber and Faber, 1996; currently only available secondhand, or via Faber print-on-demand)

The published version of this letter has been mis-transcribed as ‘Hast thou read it every day?’ (Letters, II, p. 23). Biographer Ann Thwaite’s version ‘must thou…?’ makes Tennyson’s anxiety about Emily’s voracious news reading more apparent. See Thwaite, p. 244.

Thank you, Ann, for your balanced and unbiased account of these Tennyson poems. By providing a full and fair context, you avoided a facile presentism, though you raised legitimate questions worth asking about the tone and spirit of the poems. Emily’s deep interest in contemporary events is fascinating.

Out of interest, I checked my Oxford Poems of Tennyson (1907), one of two or three I have of his works. Unsurprisingly, given the zeitgeist of those Edwardian times, I found all except one of the poems you mentioned by name were included. I query the wisdom of today’s editors in omitting them from his works, but that’s another whole debate, isn’t it!

I much enjoy how you cast light on the intimacy - and women - that underpin the broader strokes of history.