When Dorothy Pilley first began climbing in the 1910s, female mountaineers were seen as dangerously reckless and their achievements were ignored and unrecorded. But Pilley refused to accept that mountains were only for men, and she used the money she earned from her journalism to raise funds for the climbing expeditions she loved. Her memoir Climbing Days, first published in 1935, is reissued by Canongate with a new introduction by Dorothy’s great-grand nephew Dan Richards this summer; and taking place around the UK in 2024 is a ‘Climbing Days Tour’ with Dan in conversation with ‘brilliant women who embody something of Dorothy's questing, buccaneering spirit – writers and adventurers I think she would have adored’.

On 11 November 1918 Dorothy Pilley was 22 years old and working in an office in central London when news of the Armistice reached her. She rushed to Buckingham Palace, along with crowds of people, and then she spotted an irresistible challenge. ‘I saw in a flash the Victoria Memorial waiting to be climbed: white, untouched, a secret ambition of mine to scale its dizzy heights,’ she wrote in her diary that evening. Pilley was working as a secretary of the British Patriotic Women's League at the time, earning £200 a year writing newspaper articles to promote the League’s work. But her passion in life was for climbing the mountains of North Wales and Skye.

So it was natural that on Armistice Day she would use mountaineering terms to describe her joyous ascent of the 25-metre-high monument. ‘Pitches correspondingly tricky; an arm pull, then followed some ordinary scrambling onto a Cherubim's head,’ she noted. Standing triumphantly at the top, holding tightly to the golden statue of the Winged Victory, ‘I was exhilarated as only climbing can make me,’ she recalled.

Rebel women

Dorothy Pilley is one of thirteen women who feature in Sarah Lonsdale’s fascinating Rebel Women Between the Wars (2020). Dorothea, as she was known to her family, was born in south London, in 1894. Her father was a chemist and teacher who had amassed a small fortune by manufacturing baby food; her mother Annie (née Young) was a ‘free thinker’ who had rejected her Plymouth Brethren upbringing in order to marry him. Dorothy attended a prestigious girls’ boarding school and would have liked to study at Oxford, but her father refused to give his permission.

As her great grand-nephew Dan Richards writes, Pilley ‘began her independent climbing life at a time when women were often forbidden to go out to public lectures, galleries and libraries alone; to go out alone at all!’ Her father refused to help to pay for her climbing expeditions, so Pilley turned to writing as a way of earning her living.

After the War ended, she was able to stop writing dutiful articles about patriotic women and took a regular job at the Daily and Sunday Express. She loved ‘the rush of Fleet Street’ and working in a busy newspaper office, noting in 1920 that ‘to write in that heat - among a noisy, moving mob is the most exciting yet nerve-wracking experience’. Journalism gave her the financial independence she craved, but she needed to find a way of combining her skills as a writer with her love of mountaineering. As a lifelong feminist, Pilley wanted to use her experience and enthusiasm to encourage other women to follow in her footsteps, and her articles reveal her respect for nature.

‘To go up by a route unknown to the party, to come down over slopes never seen before into valleys where the rocks, the trees, the houses, the very flowers are different, seems to us to wring the best joys from mountaineering... The Trift glacier itself, as the crystal clearness of the sunrise crept down upon it, was a thing almost too exquisite to walk upon.’1

As Lonsdale observes, in Pilley’s writing ‘nature is admired and trod upon only with her consent’; it’s a far cry from the triumphalist language of attack and victory of the Alpine Journal’s articles by male mountaineers of the time.

Manless climbing

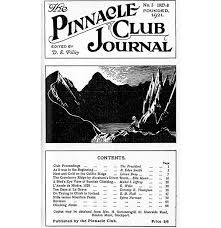

In March 1921 she became a founding member of The Pinnacle Club in Snowdonia, with the aim of encouraging rock climbing and mountaineering amongst women. She took on editorship of the Pinnacle Club Journal, which, like The Woman Engineer, launched in 1919 and published quarterly ever since, provided a public platform for women's voices to be heard without interference from male editors. Both the Pinnacle Club and its journal helped to normalize climbing as something all women could do, not just a few extraordinary individuals; the club is still going strong, 100 years on, today.

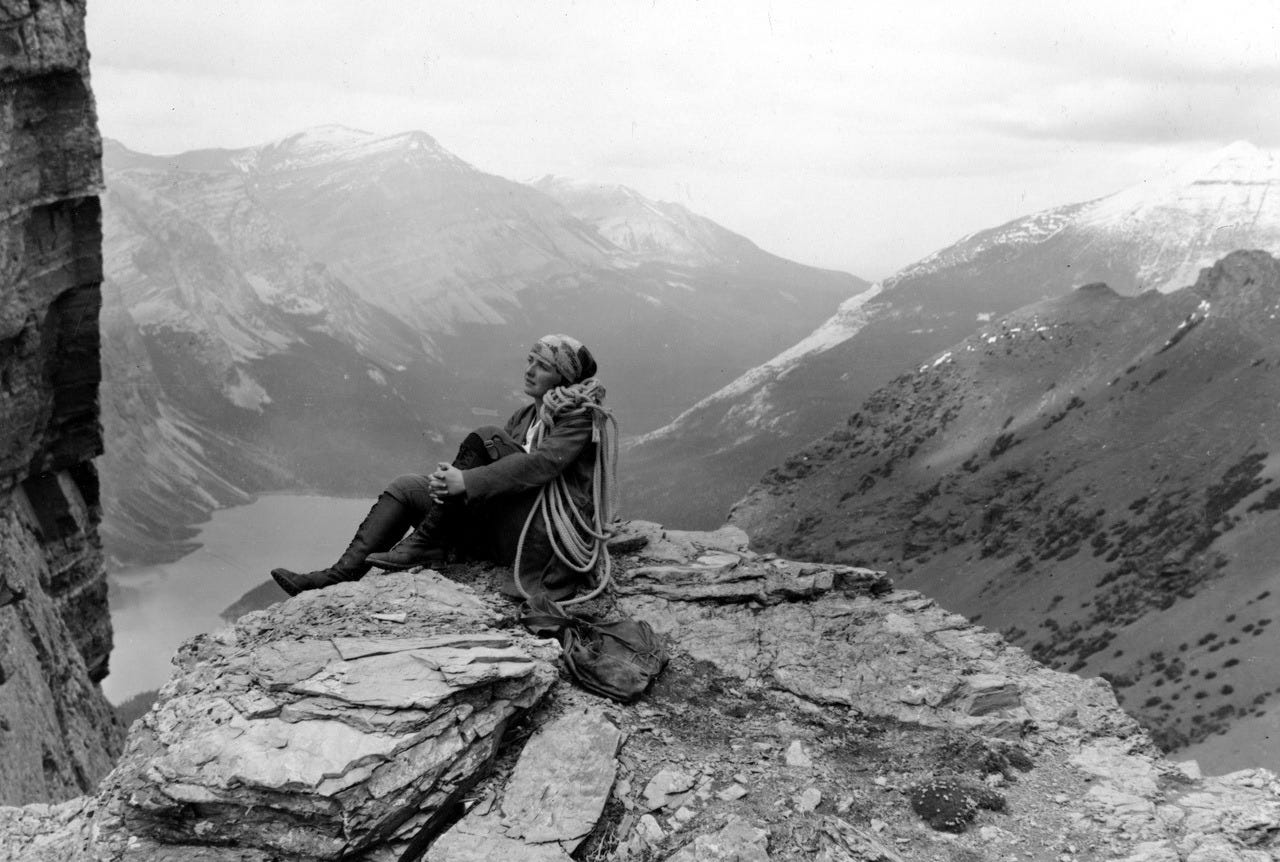

Pilley would continue to edit the Pinnacle Club Journal for the next twenty years. Its first issue contained an article called ‘Three Pinnaclers in the Alps’ by Lilian Bray. It describes how Bray, Pilley and another Englishwoman travelled by train to Switzerland during the summer of 1921. At the foot of the Matterhorn, they covered their hair with cotton bandanas, exchanged their dresses for tweed breeches and hobnail boots, and put ropes and knapsacks on their backs before scaling the traverse of the Egginergrat and the Portjengrat together. It was the first Alpine cordée féminine, or female roped party. ‘Manless climbing’ - mountaineering without male guides or companions - was seen as a dangerous practice at the time. The Alpine Club in London condemned women climbing without men’s assistance as ‘insane’, and stated that ‘few ladies, even in these days, are capable of mountaineering unaccompanied.’

A country of the mind

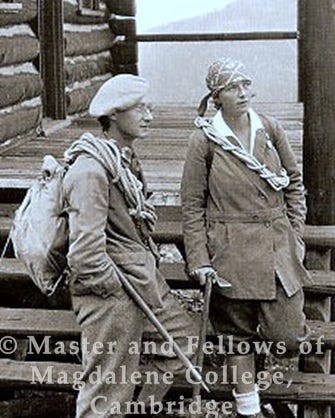

However, not all male climbers of the time doubted women mountaineers’ abilities, or their right to climb independently. The Cambridge scholar and literary critic Ivor Armstrong Richards (I.A. Richards, 1893-1979) and Dorothy Pilley had first met clambering up Tryfan in Snowdonia in 1917. ‘You were the first original thinker I had met,’ she later told him, ‘and in your conversation I discovered even as barely more than a schoolgirl the “something more in life” which I had ever so vaguely suspected – a country of the mind.’ They became close platonic friends and tackled several Alpine ascents together in the early 1920s.

In 1925 Pilley wrote a 60-page letter to Richards setting out all the reasons why she refused to marry him. She explained her conviction that marriage would mean ‘lots of housework and twenty children’, a prospect that made her ‘go cold and stiff with disdain.’ Her long letter was written from British Columbia, where she was beginning the two-year global climbing adventure that she had always dreamed of. She started by tackling the Canadian Rockies, the Selkirks and the American Rockies, with her climbs funded by her journalism for various American and Canadian newspapers.

Then, in August 1926, she was joined by a new climbing companion: Ivor Richards, who had travelled to America in the hope, yet again, of persuading Dorothy to reconsider his offer of marriage. That month they climbed Mount Baker (2, 686 metres) from the north-east side together - Pilley was the first woman to do so - and after climbing several other peaks together she was at last convinced that marrying Richards would not hold her back, or lead to a conventional life. They married in Honolulu on New Year's Eve 1926.

Ardently alive

Dorothy Pilley is known today, according to her entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, as ‘one of the most outstanding mountaineers of the interwar and post-war periods’. She became famous around the world when in July 1928 she and Richards made the first ascent of the north ridge of the Dent Blanche in the Alps, together with Joseph and Antoine Georges, thereby solving ‘one of the last great alpine problems’.2 She wrote about the Dent Blanche ascent in the final chapter of her climbing memoir, Climbing Days first published in 1935.

Thanks to Ivor Richards’ academic appointments in Bejing and Harvard, Dorothy Pilley was able to scale peaks in many different locations including China, Japan, Korea and Myanmar for the next thirty years, sometimes with Richards and mountain guides, sometimes alone. Pilley described her lifelong love of mountains as ‘the reverberation of one’s life among them. Therein, reflected, is the experience of being ardently alive.’

Sadly, Pilley’s international climbing career ended in 1958 when she was seriously injured in a car accident. While she was recovering in hospital, heartbroken that her climbing days seemed to be over, I.A. Richards wrote a poem called ‘Hope’ for her about their shared climbing history. It movingly recalls the memorable night that they accidentally spent together before they were married, sleeping on a dangerous mountain glacier. ‘‘Leaping crevasses in the dark/ That's how to live!’, you said./ No room in that to hedge,/A razor’s edge of a remark.’

In 1973, after 35 years of living at Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the couple returned to live in Cambridge, England. They moved into a set of rooms at Magdalene College, where I.A. Richards had begun his undergraduate studies in 1911, and lived there until his death in 1979.3

And Ivor was right that Dorothy’s climbing days were not over. At the age of 91, the irrepressible Pilley spent New Year’s Eve at the climbers’ hut at Glen Brittle on the island of Skye, ‘drinking whisky and talking mountains’ with a party of Scottish climbers.

On 2 July 2024 the UK publishers Canongate will reissue Pilley’s ‘inspirational’ memoir Climbing Days, first published in 1935, with a new introduction by Dan Richards as well as original maps, photographs and other material. ‘Dorothy proved herself on the slopes of Wales, Scotland and the Lake District before tackling rock faces in the Alps, the Pyrenees, the Rockies, Mount Fuji and the Himalayas,’ the publisher writes. ‘Her championing of fellow women climbers and her own trailblazing example helped establish female alpinists as serious mountaineers with impressive records on bravery, skill and endurance.’ (Bookseller, 20.12.2023)

SOURCES: Dorothy Pilley Climbing Days (1935); Sarah Lonsdale, Rebel Women Between the Wars (Manchester University Press, 2020); 'Dorothea Richards' Magdalene College Libraries blog, 7 July 2016. Dan Richards’s Climbing Days (Faber & Faber, 2016) is about following in Dorothy Pilley’s footsteps. (See also ‘Dan Talks To Interesting People’ podcast for his interview with Sarah Lonsdale) All websites accessed 2.6.2024. This is a revised and updated version of a post first published on my Wordpress blog.

Pilley, 1923, quoted in Lonsdale, p. 114.

Carol A. Osborne, ‘Richards [née Pilley, Dorothy Eleanor] 1894-1986’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, September 2004.

Dorothy Pilley remained an important part of Magdalene College in her own right. She died, aged 92, in 1986 and left a legacy of over one million pounds to the college in her will.

What a woman, what a story! I realize, with a shiver of pleasure, that my mother knew her as one of Richards’ graduate students at Harvard. The couple befriended her amd “Mrs. I.A. Richards,” as my mother called her, gave her a beautiful and unusual pair of earrings, likely a discovery from her travels. The earrings were intricately carved, and inlaid with stones in tangerine and pale green. I wonder what became of them, and how much my mother knew of Dorothy’s adventures.

Dorothy Pilley follows on the shoulders of Fanny Workman Bullock. I am reminded of her biography, QUEEN OF THE MOUNTAINEERS, by Cathryn Prince (Chicago Review Press). Like Workman, PIlley finds a husband who will not hold her back. Fascinating to read here about Pilley's life and that she eventually returned to the UK. So informative.