Written with the heart's blood

The Cambridge friendship of Amy Levy and Ellen Wordsworth Darwin

This week’s post is about the Anglo-Jewish novelist, poet and journalist Amy Levy and her friendship with the agnostic scholar and author Ellen Wordsworth Darwin, her former lecturer at Newnham College, Cambridge. After studying for two years at Cambridge (leaving without completing her degree), Amy Levy travelled widely, published three novels, two poetry collections and countless articles, and became a leading figure among ‘New Woman’ writers. Her short stories were described by Oscar Wilde as having ‘a touch of genius’, and she was highly respected as a professional woman writer. But, sadly, Amy Levy also struggled with depression and took her own life at the age of 27. Because of this, the word ‘tragic’ is often associated with her. In this post I want instead to focus on her literary success, strong work ethic and the scholarly Cambridge friendship that sustained Levy and inspired her writing for ten years.

Amy Levy at Cambridge

In 1879 Amy Levy was just 17 when she became the first Jewish student at Newnham College, Cambridge (Hertha Ayrton was the first Jewish woman to study at Girton). Levy was already a published poet, who had written an extended essay on Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Aurora Leigh when she was 13. She had attended Brighton High School for Girls, presided over by Edith Creak, one of Newnham’s famous ‘first five’ students.

Although Levy loved literature, and the prestige that came with being among Cambridge’s first women students, it’s likely that she often felt lonely there. In the close community of Newnham College, she felt conscious of her Jewish difference and found it difficult to join in with the other young women's late-night ‘cocoa’ parties and outings. She often turned down friendly invitations, saying that she had to ‘grind’ (= study). Choosing to be alone, writing essays in her room, may also have been connected to Levy’s social anxiety; she may have preferred loneliness to interacting with young women with whom she had little in common.

One friend she did make, however, away from the cocoa-drinking circuit, was Ellen Wordsworth Crofts (later Darwin), 23, who had been a Newnham student from1874 to 1877 and was now the college’s resident lecturer in English Literature and History. She had been brought up in Leeds, and was the great-niece of the poet William Wordsworth. Her uncle, Professor of Philosophy Henry Sidgwick, was one of the co-founders of Newnham College.

A friendship begins

Ellen Crofts was the first woman to teach the academic subject of English at Cambridge University, specializing in Renaissance literature. Her lectures on Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, Francis Bacon and Richard Burton were later collected and published as Chapters in the History of English Literature: from 1509 to the close of the Elizabethan period (London : Rivingtons, 1884). In the chapter ‘Decline of Elizabethan poetry’ she writes about Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy:

‘Analysis of emotion is characteristic of a declining age, and that the emotion so analysed should be that of melancholy is but a further proof of the exuberant and enjoying age of Elizabeth. The passion and strong emotion of that age had ever been of near kinship to madness.’

It’s not surprising that she found a common bond with Amy, who was only a few years younger than she was. Ellen would have been impressed by her student’s work ethic and serious ambitions as a poet, while Amy would have admired her tutor’s insights and scholarly dedication.

There may have been a protective, caring element on Ellen’s part, too. Years later, Blanche Smith (a Newnham student and a friend of both women) recalled Ellen’s kindness towards an unnamed student:

‘She from the first recognized genius in a student who, extremely unpopular, was shunned by co-mates and dons alike until Ellen made a friend of her, and so helped to draw out talents that the literary world have since acknowledged.’1

It seems very likely that this lonely student was Amy Levy, and that during her time at Newnham, Ellen was one of the few friends she had. (‘To−night you found me sad, alone, /Amid the noisy, empty books/ And drew me forth with those sweet looks, And gentle ways which are your own.’)2

In February 1881, women at Cambridge won a significant victory - after much campaigning - to have the right to sit for the university’s final ‘Tripos’ exams. But Amy Levy decided not to complete her degree course of studies (no formal degree recognition would be awarded to women by the university until 1948 in any case). It may be that studying at Cambridge had less appeal for her as its final exam requirements were becoming stricter. Her third year as a student would have involved ‘a fixed course of study’ as Levy wrote in an article published in March 1881. Newnham’s growing ambitions for its women students now meant fulfilling the University’s ‘Tripos’ requirements, and ‘mathematical classes [were being] organized for unhappy people whose souls are yearning for Plato or Mill’, she wrote.3

Mathematics did not interest Amy Levy, but literature and like-minded people did, and her literary ambitions took precedence. Her first poetry collection, Xantippe and Other Verse was published in the spring of 1881, while she was still a student at Newnham, and it was warmly praised by the influential critic Richard Garnett. She was on her way as a writer, and a well educated one, and for the rest of her life Levy would define herself as ‘a woman with a university education even while she grew increasingly critical of the academic mind.’4

Europe and London

After leaving Cambridge, Levy divided her time between travelling around Europe (following in Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s footsteps) and working in the British Library in London, where she became part of a close friendship circle that included Eleanor Marx, Olive Schreiner and Beatrice Webb (née Potter). She had, it seems, a love affair in Florence with Violet Paget, who wrote under the pseudonym Vernon Lee, but did not find the lasting romantic friendship with another woman that she longed for.

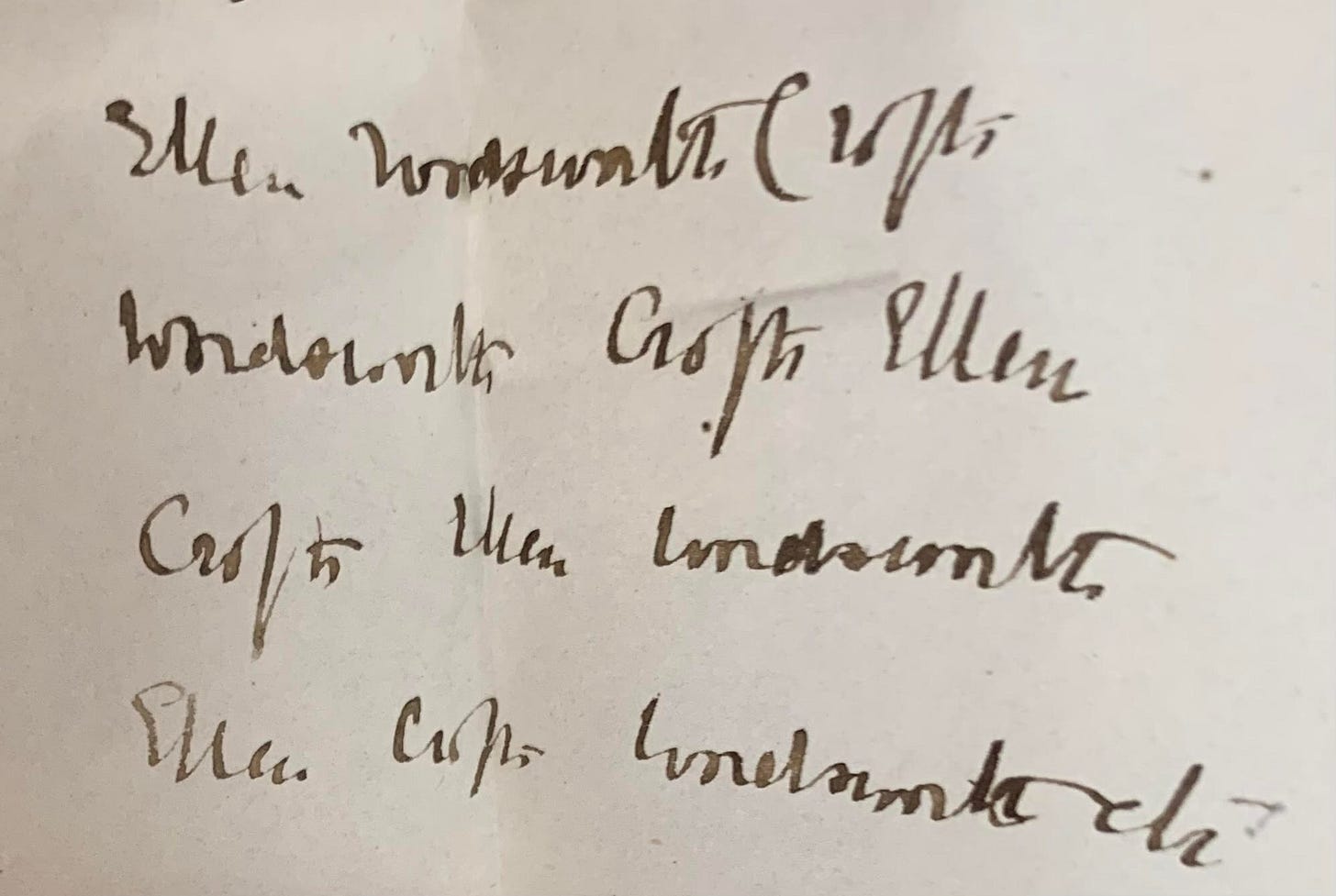

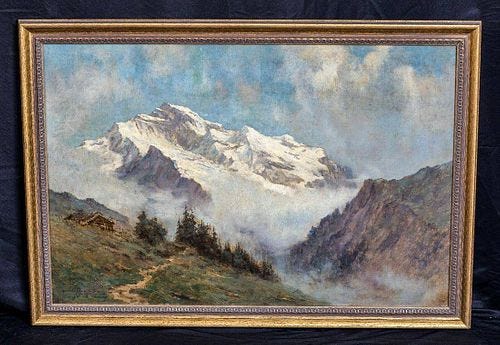

But Ellen and Amy’s platonic friendship continued. It seems that they even spent a holiday together in Switzerland in July 1883, when Ellen was there with another Newnham tutor, Mary (‘Minnie’) Ward. Ellen was giddy with happiness that summer; more than anywhere else, she loved being in the Swiss Alps and had just become engaged to be married to 34-year-old botanist Francis Darwin, who had moved to Cambridge after his father Charles Darwin’s death. ‘Dear Frank, sometimes I feel as if it could not be true, it is so beautiful’, Ellen wrote of their falling in love. Her playful signature below in a letter to him (she signs her name, Ellen Wordsworth Crofts, in four different ways) shows her humour, love of wordplay and high spirits. She loved to make her friends laugh.

In September 1883 Ellen married Frank and became stepmother to his young son Bernard. She knew that others had expected her to give up her Newnham lectureship and ambitions to be a literary scholar; but Ellen did things her own way. In 1883 Alice Longfellow (co-founder of Radcliffe College and daughter of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow) travelled from Cambridge, Massachusetts to study at Newnham for a year and was surprised to encounter not one, but two, married women lecturers in the college.

‘Mr. Frank Darwin has just married one of the lecturers here, on English Literature. She [Ellen Darwin] still continues her work, & so does Mrs. Verrall the Latin lecturer [Margaret de Gaudrion Verrall], & she has a baby in addition to a husband! They do not seem to find it incompatible, & it certainly must make their life together very delightful to be doing the same sort of work.’5

Frank and Ellen’s daughter Frances (who would become the poet Frances Cornford) was born in March 1886. Later that year Amy Levy published her short poem 'To E.' in London Society magazine. It’s about a memory of a happy day she spent with a much-loved friend in the Alps three years previously. ('You, stepped in learned lore, and I,/ A poet too.') The narrator expresses her bittersweet emotions about how both friends’ lives have changed in the intervening years. The final line strikes a sad note: ‘On you the sun is shining free... on me, the Cloud descends.’ But the poem also offers a poignant, slightly satirical view of friendship, in the style of a poet of the English Renaissance such as John Donne.

‘And do I sigh or smile to-day?/ Dead love or dead ambition, say/ Which mourn we most? Not much we weigh/ Platonic friends.’

Did Ellen Crofts Darwin, reading this, wonder if ‘To E.’ was about the day that she and Amy Levy spent together in Switzerland three years before? Was Amy sending her a coded message through her poem, perhaps gently mocking her friend’s ‘dead ambition’ as a Cambridge scholar? If so, Amy might have been envious of her happiness as a wife and mother, in contrast to her own loneliness but integrity as a poet and writer.

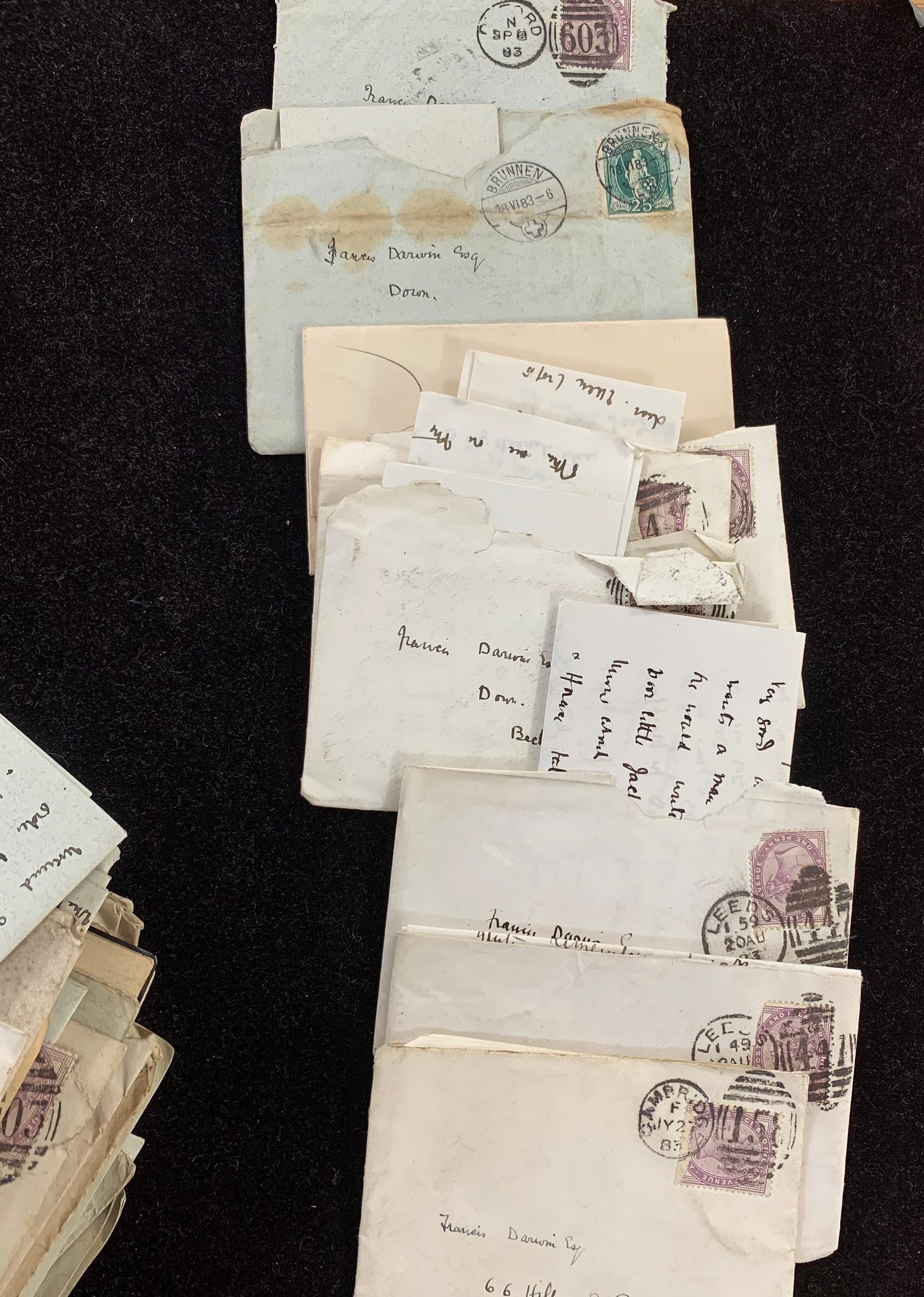

The photograph above shows a dozen or so letters written by Ellen to Frank that summer: witty, buoyant, erudite. Reading between the lines of later letters it seems that she experienced prolonged periods of melancholy and ill health, especially after her daughter Frances was born. In July 1888, she wrote longingly to her sister-in-law Ida Darwin, who was spending the summer in the Swiss Alps with her husband Horace. ‘There is nothing in the world so lovely as living high up among hills, & among other things it ought to make you well for the rest of your life,’ Ellen wrote. ‘It made me quite happy for 6 months after I came back from Switzerland once, and I felt quite smiling and contented under all circumstances.’ (July 18, 1888)

‘A touch of genius’

Levy’s literary career had continued to flourish, and her poetry, short stories and articles were published in the Jewish Chronicle. Oscar Wilde, then editor of the journal Woman's World, commissioned more work from her, including her article ‘Women and Club Life’. Her first novel The Romance of a Shop (1888) was selling well. It ‘aims at the young person’, Levy wrote, and it’s an entertaining story about the four sisters who set up their own photography studio in London. The novel shows her awareness of the tension between literary ambition and the need to earn money; ‘We all have to get down off our high horse . . . if we want to live,’ one character says early in the book. The overall theme of the book, writes Gillian Sutherland, ‘is the struggle of a group of sisters, the Lorimers, left penniless, to make a living out of photography, slowly establishing itself as a serious art form – and remain ladies.’6

Amy Levy knew that her next novel, Reuben Sachs: A Sketch, would be a much more ambitious and complex affair. Before it went to press, she wanted to discuss it with the Cambridge friend and mentor whose literary judgement she had trusted since her student days. In August 1888 Ellen wrote again to Ida in Switzerland with news that her former student Amy Levy was coming to Cambridge for an overnight visit. ‘She has written a novel, in which the heroine is partly me’, she told Ida. ‘I have not read it yet, but I don’t expect much: her stories and novels are rather saddening.’7

So it seems that Amy had her former Cambridge tutor in mind when she pictured the beautiful, serious-minded Judith Quixano in Reuben Sachs. Darwin was not Jewish, and her Yorkshire upbringing was very different from Judith Quixano's Portuguese heritage. But as can be seen in the 1903 photograph above Ellen did share what Levy describes as Judith’s ‘deep, serious gaze of the wonderful eyes’. Certainly she had Judith’s passionate nature and her unwavering sense of the importance of speaking the truth.

Controversy and criticism

Reuben Sachs: A Sketch was published in early 1889. The idea for the novel had developed from Levy's 1886 article called ‘The Jew in Fiction’ in the Jewish Chronicle in which she called for ‘a serious treatment... of the complex problem of Jewish life and Jewish character.’ Levy wanted to challenge the anti-Semitic tropes of the Victorian novel, such as Trollope’s The Eustace Diamonds (1871), and, at the other extreme, the patronizing tone of George Eliot's Daniel Deronda (1876) in which the Jewish family’s baby ‘carries on her teething intelligently’.

But from the first, Reuben Sachs attracted controversy. At the heart of the novel is the close and loving Sachs family, who give the impoverished Judith a home and treat her as one of their own. It’s a heart-rending and beautifully observed love story: the oldest son Reuben Sachs has to make a choice between following his heart or his political ambitions. Judith Quixano, who believes she has nothing to offer but her love, has no other way of finding her place in society apart from a successful marriage. ‘There is nothing more terrible, more tragic, than this ignorance of a woman of her own nature, her own possibilities, her own passions’ Levy writes.

This could be a dilemma explored in the fiction of George Eliot. But Reuben Sachs is difficult to read at times, even today; it is not just a scathing critique of the late-Victorian marriage market but also a mordant attack on affluent Anglo-Jewish materialist values. Levy’s satirical humour in the style of Emile Zola or Alphonse Daudet was not understood by reviewers, nor was her attempt to parody George Eliot, and her book was widely criticized among the Jewish community.

Amy Levy was a professional writer and did her best to shrug off all the negative publicity. She continued to take part in literary events, including helping to organize gatherings at the newly founded University Women's Club in London, and gave a speech at the first Women Writers’ Dinner held at the Criterion Restaurant in Piccadilly in May 1889. It was attended by prominent other ‘New Women’ writers including Mona Caird and Olive Schreiner.

Levy had many good friends and was making plans for her next novel and poetry collection, and to most people it looked as if she was happy and flourishing. The Irish poet W.B. Yeats was one of the few to be perceptive about her true mental state that summer. When he met her at the end of July 1889, he wrote that: ‘She was talkative, good-looking in a way, and full of the restlessness of the unhappy.’ On 10 September 1889, a month before her 27th birthday, Levy took her own life. In his moving obituary Oscar Wilde generously praised her novel Reuben Sachs (1889), saying ‘To write thus at six-and-twenty is given to very few’.

A few months after her friend’s death, in January 1890, Ellen Crofts Darwin wrote a review for the Cambridge Review of Amy Levy’s third poetry collection, A London Plane-Tree and Other Verse, posthumously published in late 1889. She describes Levy’s ‘eager vital temperament’, and her constant, heroic struggle with ‘the shadow of a great mental depression’. Levy's range might be narrow, Ellen admits with her characteristic honesty, but she describes her poetry’s power as ‘the personal struggle for life and joy continually beaten back’.

Ellen says nothing in her review about ‘To E.’, the last poem in the collection set in Switzerland, but compares Levy’s poetry to Emily Brontë's. ‘It is as different as their natures were different’ Ellen writes, ‘but it has this one thing in common – it was written with the heart's blood’.

Acknowledgements: My thanks to Nicola Beaumann of Persephone Books for including some of my writing about Amy Levy in the Spring-Summer 2023 issue of Persephone Biannually; to Linda K. Hughes for her friendly contact and for sending me her recent articles on Amy Levy (see below) and George Eliot; to Talya S. Housman at the Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site in Cambridge, Massachusetts for providing me with the information about Alice Longfellow’s Newnham Journal; and to Anne Thomson, former Newnham College archivist, for her generous assistance. I am also grateful to Newnham College Principal and Fellows for their kind permission to reproduce Ellen Wordsworth Darwin's photograph. Any remaining mistakes are my own.

Selected sources: Jenn Ashworth, ‘Amy Levy’ in Breaking Bounds: Six Newnham Lives, edited by Biddy Passmore (Newnham College Publishing, 2014); Andrzej Diniejko, 'A brief introduction to the works of Amy Levy' via the Victorian Web (accessed 4.3.2024); Eleanor Fitzsimons, Wilde's Women: How Oscar Wilde Was Shaped by the Women He Knew (Duckworth paperback, 2016); Talya Housman on Alice Longfellow in ‘Recent Writing’ (accessed 4.3.24); Linda K. Hughes, ‘Women’s minds and bodies on the move: nineteenth-century British women’s reading parties and study abroad’ (Nineteenth-Century Contexts, Volume 46, 2024, Issue 1); Linda Hunt Beckman, Amy Levy: her life and letters (Ohio, 2000); Amy Levy, Reuben Sachs (Persephone Books no.23) with a new introduction by Julia Neuberger; Gillian Sutherland, In Search of the New Woman (CUP, 2015).

Archive sources: Ellen Crofts Darwin’s letters to Ida Darwin, Cambridge University Library, Darwin Family Papers Add.9368.1:3500-600; letters to Francis Darwin, articles by E.W.D. and photographs in the Frances Cornford Papers, CUL Add. 10410 Box 4; 'In Memoriam-Ellen Wordsworth Darwin' Newnham College Roll Newsletter 1903; Ellen Wordsworth Darwin (Ellen Crofts) Chapters in the history of English literature: from 1509 to the close of the Elizabethan period (London, Rivingtons, 1884); ‘The Poems of Amy Levy’, Cambridge Review, 23 Jan 1890.

For more about Newnham College women, see also my recent posts ‘Not Afraid of Virginia Woolf’ and ‘Sylvia Plath At Home’.

Blanche Smith, ‘In Memoriam.–Ellen Wordsworth Darwin’, Newnham College Roll Newsletter 1903.

‘Ralph to Mary’ from Xantippe and Other Verse (1881) by Amy Levy.

Amy Levy, quoted in Linda Hunt Beckman, Amy Levy: her life and letters (Ohio, 2000), p.57.

Beckman, p.8.

Alice Longfellow (1850-1928), Journal of a year in England at Newnham College, 1883-1884, in the Alice Mary Longfellow Papers (LONG 16173), Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site (17 October 1883).

Gillian Sutherland, In Search of the New Woman (CUP, 2015), p. 57.

This was such an interesting read! And Levy is new to me so thank you for the new writer to explore.

I love that I found your work--these stories are so important for more people to know, and I'm grateful to learn more about Levy's work--I bought Romance of a Shop some time ago after first learning about her, but knew little else. And how much the work of creators is truly a web tied to other strings for anchors--fantastic read!