Given all the recent (and ongoing) upheavals leading up to the 2024 U.S. presidential election, it won’t be long before we hear that these are ‘unprecedented times’ for American politics. But have you ever heard of anything being ‘precedented’? Yes, the word really does exist, but you have to go back 225 years to see it used, according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary. ‘In its initial use, in the beginning of the 17th century, the word was spelled presidented’ the editors write. ‘Happily, we didn't stick with that.’

In this week’s post I look back at the part played by the English author and lecturer Emma Hardinge Britten (1823-1899) in the equally unprecedented presidential campaign of 1864 in which President Abraham Lincoln stood for a second term while the Civil War was still raging. This is the first in my series of historical biographies of international women.

The spiritualist craze

In her recent book Out of the Shadows Emily Midorikawa traces the origins of the nineteenth-century Spiritualist movement to a small hamlet called Hydesville in New York County in 1848, where two young sisters appeared to be contact with unseen presences. The ‘Rochester rappings’ made Kate and Maggie Fox famous, and soon, together with their older sister Leah Fox, they were giving public demonstrations to large crowds in concert halls throughout North America.

By the 1850s the interest in spiritualism had crossed the Atlantic Ocean, and reached all social classes in Britain. ‘Table turning particularly caught on among working people in the Yorkshire town of Keighley, with its history of social and political radicalism’, Midorikawa notes, ‘as well as with the leisured classes residing in the nation’s capital.’ Charles Dickens was sceptical about what he described as a ‘miserable delusion.’ (Mesmerism, which he practised, was considered to be a more ‘masculine’ pursuit and therefore more scientific.)

But his words had little effect: well-educated people were attending séances in elegant drawing-rooms all over the country, while Cambridge University would soon become the centre for ‘scientific investigations’ into spiritualist phenomena. Queen Victoria recorded in her diary how, during their spring holiday at Osborne House in 1853, she and Prince Albert engaged in a table-turning session with their ladies-in-waiting. Victoria refused to believe that “so many hundreds, if not thousands, high & low” could simply have “performed a trick!”.

A romantic adventure

In the early 1850s an actress known as Miss Emma Harding was struggling to make a living in London. She had hoped to become an opera singer, and composed music under the pseudonym Ernest Reinhold. But her earnings as a composer were not enough to support herself and her widowed mother, and she took parts as a dancer, appearing in humorous Romantic ballets such as The Phantom Dancers at the Adelphi Theatre. ‘The career of struggle, romantic adventure, and fearful effort I led in England, is too much of the wild and wonderful for print’, she later wrote in her autobiography.1

It’s likely that Hardinge’s light-hearted tone here, in keeping with the fancy footwork she was adept in as a professional dancer, disguises a much more painful truth about her earlier life. It seems that a group of wealthy individuals and aristocrats she later referred to as ‘the Orphic Circle’ involved her and other young women in secret experiments in which they were put in a trance-like state, and possibly drugged.

‘my career of struggle, romantic adventure, and fearful effort’

In a last-ditch effort to revive her acting career, and escape from this group’s influence, Hardinge took up the offer of nine months’ work in a Broadway production and sailed to New York with her mother. There the part she was promised failed to materialise, and for a time it looked as if she would have no choice but to return to England. But before long she met the medium Mrs Ada Foye who introduced her to others involved in the American séance scene, and, spotting Emma’s woman’s talent for public speaking, encouraged her to give up her stage career and take up ‘trance lecturing’ instead. Emma became Mrs Hardinge

Her first public performance was a musical one, with a group of fifty singers performing a ‘spiritualist’ cantata of her own composition. Modestly she claimed it was composed by ‘a power that worked through my organism’. The New York Herald was cynical about spiritualism but impressed by her talents, reporting that ‘whoever the Spirits that controlled Emma Hardinge might be, they could at least make good music’. She might rise to become one of the leading musicians and composers of the age, they said, but only if she chose to ‘give up the shadow’ of spiritualism.

‘When women had to channel the dead to be heard’

But perhaps Emma Hardinge could see well enough into the future to predict that her gifts as a public speaker, combined with her stage presence, would take her even further. Before long she was travelling around Canada and North America, treading the boards and ‘trance lecturing’ before distinguished male audiences including priests, lawyers, doctors and reporters, and answering their questions. ‘To a woman in her thirties with little formal education, this must have been daunting indeed,’ Midorikawa writes.2

As with her music compositions, Hardinge claimed to have no awareness beforehand of what the spirits would tell her to say, which included outspoken (and therefore unladylike) views on controversial topics of female emancipation and the need to have sympathy for the plight of fallen women. In 1859 she gave a lecture called The Place and Mission of Women, which was later reproduced in pamphlet form and argued that women ‘should have the right to enter schools, and the associations of commerce and trade’ and even ‘hold positions in the government.’ This was years before women had the right to vote. Later, her support for the abolition of slavery caused anger in the South, and in January 1860 she arrived in Alabama to find spiritualist lecturers were banned there.

As Midorikawa says, when it came to speaking up on behalf of other women and enslaved people, it was more acceptable for Emma Hardinge to tell herself and her audience ‘that she was merely a mouthpiece for dead – usually male – spirits.’3

The Coming Man

During the Civil War Hardinge continued to tour and give lectures in the North, and as her fame and audiences grew, she became more confident in her oratorial skills. In 1864 she gave a lecture in San Francisco in support of the National Union Party, entitled ‘The Coming Man; or the Next President of the United States’. The election to be held on 8 November 1864 was unprecedented, because no American election had ever taken place during a war before. Abraham Lincoln had been President since 1860 and seemed unlikely to be elected for a second term.

But his campaign team was so impressed by Hardinge’s power of oration that they asked her if she would ‘stump the State for Lincoln’. Because it was unheard of to employ a woman for this role, the understanding was that it would be an unofficial arrangement. Hardinge was scathing about the wealthy, powerful men who ‘could not for a moment condescend to the indignity of employing a professional speaker, and that speaker a woman’ but she agreed. The Union Committee agreed to pay her expenses and she gave a thirty-two lecture tour and drew huge crowds everywhere she went. As Midorikawa writes, Hardinge’s unusual status as “Female Campaign Orator” proved even more novel than that of someone who channeled the thoughts of dead men’4 and helped to ensure Lincoln’s resounding victory in California in November 1864.

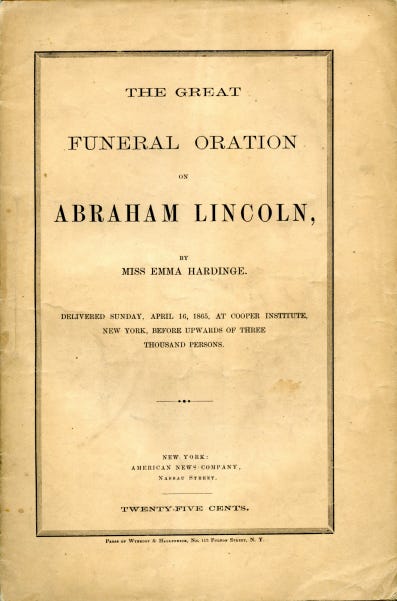

Tragically, Lincoln was assassinated just two months into his second term, on 15 April 1865. Soon afterwards, Hardinge was asked to deliver the funeral oration for the President in New York City, the first time a eulogy on this scale had been given in the city. Standing before an audience of over three thousand people, just thirty-six hours after the president’s death, she gave her ‘Great Funeral Oration on Abraham Lincoln’, with its plea for peace between North and South.

‘Mourn for Abraham Lincoln with your hearts, but prove your love to him by taking up the burdens he’s laid down and finishing the noble purposes of his great life so untimely quenched.’ Emma Hardinge, 1865

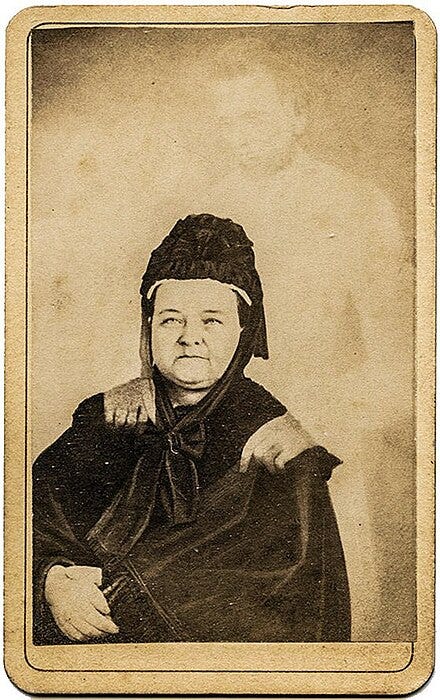

The Lincolns and spiritualism

There was no mention of the spirits in Hardinge’s most famous speech, but privately she had no doubt that Lincoln was interested in ‘the cause of Spiritualism.’ It was well known that the president’s wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, had held séances at the White House to try to contact their young son Willie, who died during Lincoln's first term in office. Later Mrs Lincoln was photographed by the ‘spirit photographer’ William H. Mumler, with the ghostly presence of her husband behind her, his hands resting protectively on her shoulders. Emma Hardinge had her photograph taken too, with an unknown figure behind her.

Read about Emma’s marriage, career and ‘Seven Principles’ of spiritualism in Midorikawa’s book; for more details, see below.

Emma Hardinge Britten is one of six extraordinary woman who feature in Emily Midorikawa’s group biography, Out of the Shadows: six visionary Victorian women in search of a public voice (Counterpoint paperback, 2022). It’s a thoroughly gripping and well researched book that reveals how these women made successful careers out of spiritualism on both sides of the Atlantic, taking their talents as passive mediums at séances in private drawing-rooms to speaking to thousands via the public stage.

Now over to you! What historical woman has made an impression on you, and you think should be better known?

Recommended reading

‘She who would be president’ by

; ‘The women members’ room’ by ; ‘The Best 19th-c. Woman Writer You Don't Know But Should’ by '; ‘Jennie Jerome’ by ; ‘Who we’ve forgotten’ by ; ‘Lee Krasner: Artistic Trailblazer’ byAnd if you like reading about independent and enterprising women, have a look at these:

Autobiography of Emma Hardinge Britten (London, 1900). Quoted in Emily Midorikawa Out of the Shadows: six visionary Victorian women in search of a public voice (Counterpoint, 2021/2022) p.58.

Midorikawa, p. 82.

Midorikawa, p.82. See also ‘When Women Channeled the Dead to be Heard’, https://daily.jstor.org/when-women-channeled-the-dead-to-be-heard/ (accessed 22 July 2024).

Midorikawa, p.100.

This is extraordinary. I’ve heard of Spiritualism, and of Mary Todd Lincoln’s deep involvement in it, but this story is entirely new to me. Thank you for sharing it, Ann!

Fascinating. I had never heard of her. That she gave the eulogy in NY seems little less than extraordinary, somehow. I hope that she went on to have a good rest of her life. Thanks for this!