This week’s post is about a subject close to my heart. It’s about how, between 1904 and 1907, over 700 former students of Oxford and Cambridge travelled from England by steamboat to Trinity College, Dublin to be awarded the degree certificates which they had earned, but which their own universities had refused to give them as women. During those three years, lasting links were forged between past and present women students at Trinity College Dublin and at Cambridge University, as a historic gift reveals.

Women undergraduates were first admitted to Ireland’s oldest university, Trinity College Dublin, in 1904. One of the most important episodes to raise its academic reputation was the awarding of ad eundem gradum (an academic degree awarded by one university to an alumnus/alumna of another) to women who had studied at Cambridge and Oxford in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but had not been given degrees. Girton College was the UK’s first residential institution, offering university education for women from 1869, and Newnham College Cambridge accepted its first five students two years later. Oxford’s first women’s colleges were established in the late 1870s (see my post on Louise Creighton here).

Oxbridge degrees

But although by this time women had been studying at degree level and succeeding in final year exams at Oxford and Cambridge for over thirty years, they continued to be refused degrees at the two oldest English universities (London and other UK universities accepted women on equal terms). In 1897 there were protests at the prospect of women being awarded B.A.s, and calls for ‘No Women at Cambridge.’

In 1904, Trinity College Dublin had agreed to open its doors to women students for the first time, but it needed money to build a hall of residence for them. Then a former student of Girton College Cambridge came up with a bright idea. She suggested to the Provost that a good way of raising those funds might be to offer ad eundem degrees to ‘Oxbridge’ women like herself and many others. On 4 June 1904 TCD’s Board passed a resolution stating that:

‘Women Students or Graduates of other Universities in which women are given full academic status, are entitled to every privilege granted to men of the same standing.’

The first TCD degrees to be awarded were honorary D.Litt. (doctorates) to three Irish female pioneers in higher education: Jane Barlow, Isabella Mulvany and Sophie Bryant in 1904. The following year, Ellen McArthur (Girton, 1882) was the first woman from Cambridge University to be awarded an honorary doctorate. For the next three years, over 720 pioneering students who had studied at Oxford and Cambridge (mostly now employed professionally as headmistresses, teachers and university lecturers) took leave from their jobs to travel to Dublin and receive the degrees they had rightfully earned.

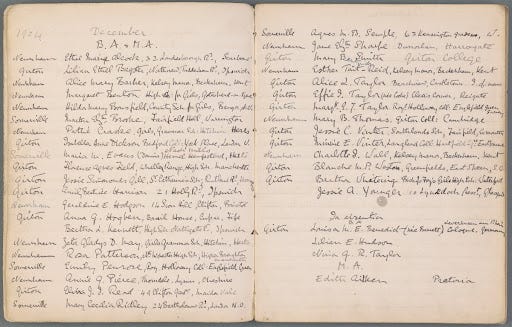

These Oxbridge women were nicknamed the ‘Steamboat Ladies’ for the cheap ferry transport they often used to to cross the Irish Sea from Holyhead; each paid £10 and 3 shillings to be awarded their rightful degree, and their names were officially recorded in Trinity College Dublin’s Commencements lists.

Inviting Oxbridge women to attend a formal graduation ceremony on the same terms as male undergraduates was an unprecedented act of forward thinking on the part of Trinity College Dublin in 1904, especially given that it had itself for so long resisted campaigns to admit women students.

As Susan M. Parkes writes in her book A Danger to the Men? A History of Women in Trinity College Dublin 1904-2004 (Lilliput Press 2004), the Board had presumed that only a handful of Irish women who had studied at Oxford and Cambridge would take up the offer, and were surprised when so many women of different nationalities took unpaid leave of absence from their jobs and made the journey to Dublin.

‘These distinguished women of varying ages were the leaders of women's secondary and higher education in Britain’ Parkes writes. ‘Trinity was honoured by their presence, and though the majority of the “Steamboat Ladies” probably never returned to Dublin, they remained proud holders of University of Dublin degrees.’

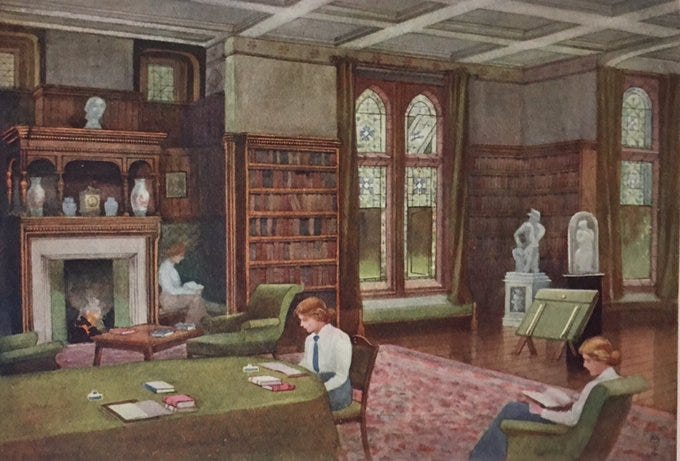

Seeing so many pioneering professional women gathered together - among them lecturers, senior civil servants, medical doctors and journalists - must have been inspirational to Trinity's first generation of female students who were starting their degrees. On regular occasions from December 1904 to 1907 they could watch the gown-and mortarboard-wearing Oxbridge women proceed from the Provost's house (where they had been given a good lunch) to the college's gracious Front Square where they posed for photographs on the steps of the Dining Hall.

There’s lots of interesting extra information in this Trinity Today article from 2022, ‘Trinity and the Steamboat Ladies’, and in the connected online exhibition ‘If a female had once passed the gate…’ .

The first Cambridge woman to receive an honorary doctorate (D.Litt.) from TCD was the historian Ellen McArthur, in recognition of her groundbreaking academic publications.

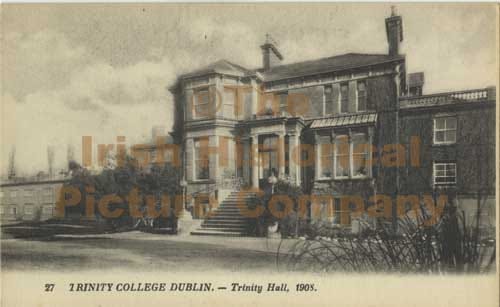

The final ad eundem degree ceremony for Oxbridge women took place in 1907. The revenue generated enabled the purchase of a sizeable new hall of residence for Trinity’s women students in south Dublin, which today is a cluster of residential halls set in peaceful tree-filled grounds.

Eileen Power (1889-1940)

Hello and welcome to Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society. In this post, part of my series about women academics who were educated at Cambridge University, I consider the life and influential work of the British economic historian and medievalist Eileen Power (1889-1940).

The first Warden of Trinity Hall, who would stay in post for the next thirty-two years, was Elizabeth Margaret Cunningham, who had studied modern languages at Girton College, Cambridge in the 1890s and was one of the first ‘Steamboat Ladies’, travelling to Ireland from her post as a lecturer at Royal Holloway College London. In 1908 she gave up her academic career there and returned to Dublin to make Trinity Hall a welcoming place for TCD’s female students. She wanted Trinity’s women students to experience the atmosphere of encouragement and support that she had enjoyed while studying at Girton College.

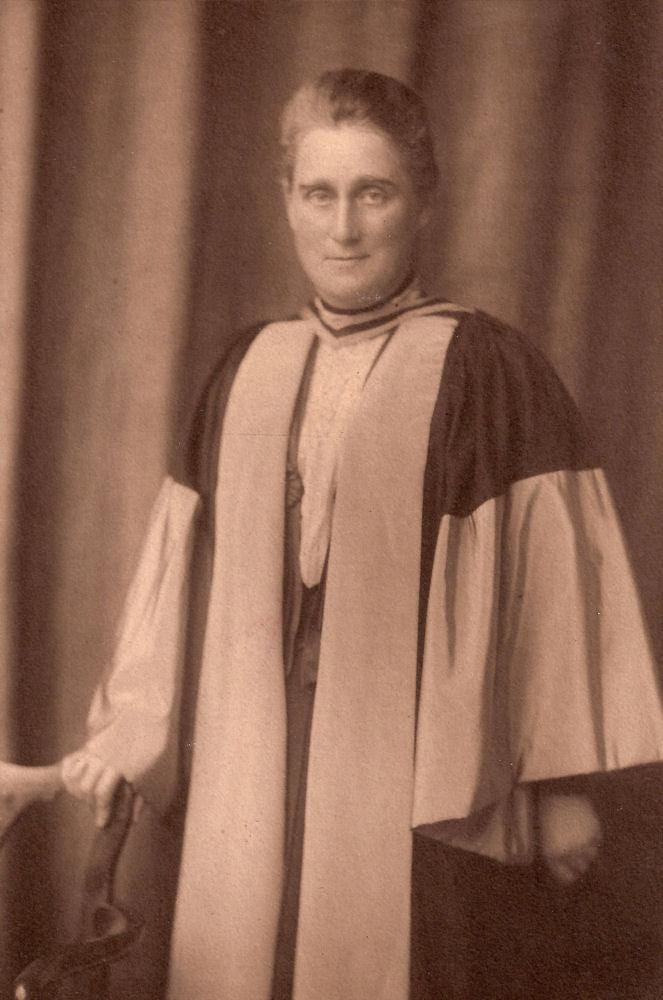

has researched and written about the contribution to economics of another of Girton’s ‘Steamboat ladies’: Hélène Reynard.In 1968, sixty years after the first women’s residence at TCD, Barbara Wright (née Robinson), who had completed her Ph.D. degree at Newnham College Cambridge in 1962, became one of the first four women to be elected to the Fellowship of Trinity College Dublin. To mark the occasion, Dame Ruth Cowen (then Principal of Newnham College) gave her a remarkable gift: one of the original graduation gowns worn by Newnham’s Steamboat Ladies from 1904-7. It was a reminder of the century-old link between Dublin and Cambridge women in higher education. In a 2019 broadcast, Professor Wright said:

I thought that was really moving that [Newnham] wanted to mark the full accession of women to all stages in Trinity, in gratitude for what Trinity had done for them. These were very important women, in society, and in the world of learning, and it was extremely important that they should be recognised as such.

It was wonderful to see this historic gown on display in Cambridge University Library’s 2019-20 exhibition 'The Rising Tide: Women at Cambridge' (my review in the Times Literary Supplement here).

As a Trinity student in Dublin in the early 1980s I was fortunate enough to be taught by Prof. Barbara Wright and it was partly thanks to her inspiring teaching that I moved from Dublin to Cambridge to study for my own Ph.D. in French Literature in 1985. It’s lovely to think that historic, tangible connections between those pioneering women at Trinity College Dublin and at Cambridge University continue to have an influence today.

With thanks to Ciara Daly, TCD Dublin Archivist for her generous advice. I highly recommend TCD’s excellent online centenary exhibition, ‘If a female had once passed the gate…’

Cambridge Notebook #8

‘Lock up your libraries if you like; but there is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind.’

The perseverance of women, I feel, often goes unseen. This really does show that, brilliantly written and detailed.

I literally cannot fathom the commitment and toughness these women possessed to push back against the prevailing attitudes and structures of the day. Would love to hear more about their family stories re the gamut from support to opposition.