Hello and welcome. It’s a great pleasure this week to be able to showcase a guest post by Dr Sarah Lonsdale, author of a new group biography, Wildly Different: How five women reclaimed nature in a man’s world (MUP, 2025). I have long been a fan of Sarah’s writing, and a few years ago had the pleasure of reviewing her book Rebel Women Between the Wars (MUP, 2020) for History Today (see my post about it here). Her new book features five women who represent the worlds of exploration, scientific discovery and environmental conservation, and the excerpt here focuses on the early life of the British entomologist, Evelyn Cheesman (1881–1969). Like many of the women I write about in Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society, she was denied the opportunity of studying at university but that didn’t stop her from getting an education through her own efforts, and doing the scientific work she was so determined to do.

(Abridged extract from Wildly Different Chapter Two)

The island was full of noises. And snakes. The sawing and whining of unseen insects and tree frogs, a symphony of tiny drills, counterpointed the constant drip of water permeating through layers of leaves. All was mossy fringe, tendril, spike, pod, scale. And beneath it all the shuddering boom of the Pacific waves coming to rest against the shore. Gorgona, just off the coast of Colombia is an island rainforest: the mahogany, balsa and banyan figs as well as the orchids, epiphytes and tropical ferns in trees eight storeys tall, harbour more than 400 species of reptile, many deadly. The snakes inspired Spanish explorer Diego de Almagro in 1524 to name the uninhabited island Gorgona after the serpent-haired women of Greek myth, who could turn men to stone with one murderous look.

Evelyn Cheesman had no time to consider cartographical etymology nor the monstrous-feminine of ancient poets’ imaginings. She was trapped in the bonds of a giant spider’s web from which no amount of chewing or tearing with her teeth and fingers could release her. The more she tugged, the more the silk, stronger in tensile strength than steel, cut into her hands. While she was too large to be considered a meal for the spider that had woven this web, the sight of a shrivelled and decidedly post-mortem gecko hanging from the skein in front of her was not encouraging. She had been trapped like this for over an hour, having momentarily lost concentration as she wandered through this strange country that thrilled her with its tintinnabulating life.

It would never do, so early on in the two-year journey for the expedition’s only woman scientist to have got herself trapped inside a spider’s web.

She had joined a scientific expedition to the South Pacific in order to gather exotic species for the Zoological Society of London, where she was curator of the Insect House. When she had started work as a lowly keeper at the Zoo in 1917, wartime visitors seeking escape from the food shortages and relentlessly grim news were satisfied with the paltry collection of native mayflies and aquatic beetles. Now, six years after the end of the First World War, the public was demanding more to see than the bugs she had scooped out of Home Counties ponds and hedgerows.

She was currently trapped and in danger of being collected herself, by a giant Nephila spider, and her expedition, on a tight schedule and next bound for the Galapagos, wouldn’t wait more than a few hours for her. The party had left Dartmouth three months earlier, in April 1924, aboard the three-masted steam yacht the St George. Its departure was a minor news sensation, dubbed by the Daily Mail as a ‘Second Voyage of the Beagle’ after Charles Darwin’s famous expedition to the Galapagos nearly one hundred years earlier. It had been difficult enough to persuade the Scientific Expeditionary Research Association’s all-male committee that a woman entomologist should be one of the eight scientists on board, their free passage covered by the tickets of the other passengers. It would never do, so early on in the two-year journey for the expedition’s only woman scientist to have got herself trapped inside a spider’s web.

Lucy Evelyn Cheesman was born at Court Lodge, Westwell, on the 8th of October, 1881, the middle of five imaginative and precocious siblings, daughter of affectionate if distracted parents who allowed their offspring to roam the little river valley behind the house alone. Very often the children’s sole guardian on these forays into deep banks of mud or forests of stinging nettles, was their devoted Collie dog, Shep.

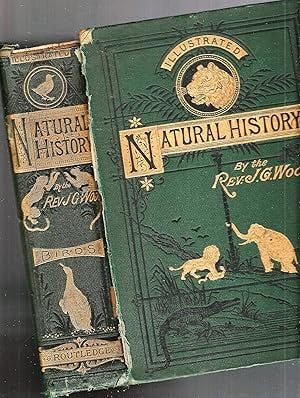

The children’s Bible was the three volumes of the Reverend John George Woods’ Illustrated Natural History for Children. Robert, the eldest son, got Volume I, ‘Mammals’, Edith, ‘Birds’ and Evelyn ‘Fishes, Insects etc’. Sitting in the nursery, or lying in bed recovering from one of the severe attacks of bronchial asthma that she would endure throughout her life, reading and looking at the illustrations, Evelyn was transported. She read of the glow-worm: ‘In a dark night these diminutive creatures shine with such brightness as to bear some resemblance to stars.’ Woods continued, ‘It is commonly met with under hedges and, if taken up with care, may be kept alive for many days, upon fresh tufts of grass.’

That June, Evelyn explored the lanes around Court Lodge with Shep and brought back 32 glow-worms, which she kept in jars in the nursery. Lying in bed at night, she watched the bright stellate lights adorn the shelves of the room, a complete and private universe of living stars. After the glow worms came toads, cockchafer beetles that flew around the nursery like miniature bi-planes, and then the pale and stately Roman snails which, let loose inside the house, left ‘wonderful silver filigree-work over carpet and furniture’. The children marvelled but the snails were thrown out.

Lying in bed at night, she watched the bright stellate lights adorn the shelves of the room, a complete and private universe of living stars.

Evelyn, naturally, wanted to be a vet but the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons would not admit women until 1927. Evelyn had applied twice, once using her full name and a second time using a male pseudonym but foolishly the same surname and address so the admissions officers saw through her ‘ruse’ and she was rejected again. Evelyn’s difficulties in pursuing a career in the sciences mirrored the experience of many other women of this time. Through the second half of the nineteenth century, women had begun to study at university, although, initially, they were not admitted to degrees. Bedford College, based in central London, and founded in 1849, was the first institution to provide higher education for women, from the start offering classes, a guinea a time, in natural philosophy, plant biology and chemistry although initially there were no laboratories. The women students, as at other universities, initially had to beg or borrow laboratory space and the use of microscopes, or study, secretly, in the long summer vacation when the eminent male professors, many of whom refused to teach women science, were away.

On her return from that first collecting expedition, Evelyn left London Zoo and started work as a volunteer entomologist in the British Museum’s natural history department (now the Natural History Museum) where she would work, on and off, for the next three decades in between lengthy collecting expeditions to other parts of the Pacific. Ultimately more than 200 new species of insect would be named after her and in 2010 bio-geographers proposed a ‘Cheesman Line’ in Vanuatu, similar to the famous Wallace Line in Australasia, in recognition of her work in linking variations in insect distribution and the great tectonic movements of the earth.

©Sarah Lonsdale, 2025

‘Wildly different is an urgent, timely and original study of five pioneering women who fought for the right to explore and protect the wild. Sarah Lonsdale writes from the heart, and nothing has brought home to me with more force the relationship between gender and the natural world.’

Frances Wilson, author of The Ballad of Dorothy Wordsworth

‘It’s a deeply felt, splendidly told, long overdue celebration of five wild, witty and wise voices who make a compelling case, now as then, for conservation, compassion and community.’

Dan Richards, author of Climbing Days

Do you have a favourite travel memoir? I got some intriguing answers when I asked this question yesterday via Substack Notes, including Roughing It by Mark Twain; ‘Anything by Eric Newby. I love his humour’; William Dalrymple’s From the Holy Mountain and Greek To Me by the ‘Comma Queen’, Mary Norris; Dervla Murphy and Freya Stark among others. I wrote about some contemporary travel memoirs by women writers here, and would love to hear what else you would recommend, and why.

Speaking of travelling, I had a trip to the Barbican theatre in east London last week, and also visited ‘St Giles’ Cripplegate’, which among other things is where Oliver Cromwell got married and the burial place of John Milton in 1674. There’s been a church on this spot for over 1,000 years and the name ‘Cripplegate’ refers to one of the gates through the old City wall which in Roman times served as a fortification to protect the city from attackers: ‘it is likely that the word comes from the Anglo-Saxon “cruplegate”, which means a covered way or tunnel.’ But Saint Giles is also the patron saint of people with physical disabilities, so perhaps the two meanings have merged over time. There’s a good secondhand bookshop in this peaceful, light-filled London church.

If you enjoyed this post, you might like reading about other intrepid women travellers (most with Cambridge University connections) in some of my previous posts below, all without a paywall this week. And if you feel you’d like to upgrade to a paid subscription to support my ongoing research and writing, that would fill me with delight – there’s currently a time-limited offer which ends May 17. I also really appreciate your ‘likes’/hearts, comments and shares; thank you very much for reading.

Steamboat Ladies

This post is about a subject close to my heart. It’s about how, between 1904 and 1907, over 700 former students of Oxford and Cambridge travelled from England by steamboat to Trinity College, Dublin to be awarded the degree certificates which they had earned, but which their own universities had refused to give them as women. During those three years, lasting links were forged between past and present women students at Trinity College Dublin and at Cambridge University, as a historic gift reveals.

Eileen Power (1889-1940)

Hello and welcome to Cambridge Ladies’ Dining Society. In this post, part of my series about women academics who were educated at Cambridge University, I consider the life and influential work of the British economic historian and medievalist Eileen Power (1889-1940).

Manless climbing: Dorothy Pilley (1894-1986)

When Dorothy Pilley first began climbing in the 1910s, female mountaineers were seen as dangerously reckless and their achievements were ignored and unrecorded. But Pilley refused to accept that mountains were only for men, and she used the money she earned from her journalism to raise funds for the climbing expeditions she loved.

A woman's life on the road

Hello and welcome. I’ve been lucky enough to have been asked to review some excellent nonfiction for the TLS and other literary journals in 2023, and one trend that has emerged strongly is the travel memoir. Perhaps this renaissance of the travel writing genre is due to writers emerging from the cocoon-like restrictions of the worldwide Covid-19 pandemic, or maybe there’s another reason known only to publishers. But armchair traveller and archive explorer that I am,

Now I'm consumed with curiosity about how Miss Cheesman managed to free herself from the spiderweb ... !

"She was trapped in the bonds of a giant spider’s web from which no amount of chewing or tearing with her teeth and fingers could release her. The more she tugged, the more the silk, stronger in tensile strength than steel, cut into her hands." Indiana Jones meets Charles Darwin... This is such an engrossing and well-told story and good to find out about Cheesman. Thank you for such a great post!